Alternatives to Olympic Weightlifting For Power Development

Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

This is a guest post written by Vancouver-based personal trainer and S&C coach Jason Lau of Performance Purpose. Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

Olympic Weightlifting for S&C

Olympic Weightlifting is a sport in which athletes attempt to lift a maximum weight overhead using the two competition lifts: Snatch and Clean & Jerk. These competition lifts and their derivatives: hang snatch/clean, push press, snatch/clean pulls, power clean/snatch/jerk, can often be seen programmed outside of the sport, in an athlete’s strength and conditioning program.

Due to the identical triple extension movement pattern (extension of ankles, knees and hips), seen commonly in weightlifting and sports, an athlete training the weightlifting movements can greatly improve the transfer of power from feet through torso to hands, as well as athletic coordination. In that sense, weightlifting can serve as a specific preparatory exercise that matches the high force and high velocity seen in sport that traditional heavy lifting cannot satisfy.

To quote Cal Dietz – “In order for an athlete to become fast, they must train fast.”

Then Why Use Alternatives?

Despite the power development that the weightlifting movements provides for athletes, there are also risks that you will have to consider as well.

Aside from aggravated joints such as knees, shoulders and hips, the lifts requires a high technical demand to perform correctly and safely. Time is required to master the technical aspect of the lifts. Time that should not be carelessly managed when an athlete is training for an upcoming game or season. Another factor to consider is the amount of training experience the athlete has in the weight-room. Mobility and injury restrictions may also interfere with the athlete’s ability in performing the lifts. Lack of ankle and overhead mobility and stability are restrictions are common and should be addressed before progressively overloading as it may lead to injury down the road.

Power development is also specific. In the world of S&C, specificity is king as game/competition date draws close. Does the athlete have to move heavy external or light loads within the sport? This will determine what type of loading scheme and stimulus is required. For example, a football linebacker will lean towards higher intensity hang cleans including prioritisation of strength due to the demands of their sport. On the other hand, the intensities a volleyball athlete’s program would see lighter intensities as external load is not needed to the same degree within the sport.

By taking into consideration of the limitations listed previously, alternatives can be performed and taught with relative ease while mimicking the classic lifts in velocity and movement pattern. Through alternatives, we can achieve the same stimulus that weightlifting movements bring while still improving strength in high-velocities.

Alternative Exercises

Trap Bar Jumps – Trap Bar Jumps is one of the go-to replacements for weightlifting. A previous study done by Timothy J. Suchomel indicates that when utilizing lighter loads (<40% of 1RM), the jumps displayed higher force output compared to a hang power clean at the same load. The learning curve of this exercise is relatively low where the majority of athletes can perform without difficulty while staying true to the natural movement pattern of jumping. With the versatility of the trap bar jump, it can be performed with a counter-movement while loaded with bands or weights.

Squat Jumps – Squat Jumps is a great transition towards power as an athlete is transferring out of their strength focused block. Aside from a smooth transition, a squat jump replicates the second pull during a clean. This can be performed from a quarter squat depth or full squat depth, all dependent on the athlete’s goals. Considering this exercise utilizes the squat movement pattern, it is different from an athlete’s natural jumping form so it may not satisfy the need of specificity.

Medicine Ball Toss – The med ball toss is a great exercise to have within one’s arsenal. Ballistics are predominantly concentric in nature allowing the athlete to focus on the acceleration phase without having to catch or decelerate at the end. The ability to reap the benefits of fast twitch muscle fibre contractions without the negative effects of eccentric forces can benefit the athlete. Tosses can be expressed throughout multiple planes of motion as well, not only vertically, that is what makes this movement so versatile.

Prowler Push – The vast majority of alternatives are bilateral in nature, but with Prowler Pushes and drags, we can achieve unilateral power with little technical demand on the athlete. This allows the athlete to drive off the ground and transfer force through the torso and into the prowler with no eccentric forces. This movement is versatile and can serve as a special developmental exercise for athletes in frequent sprinting sports.

To weightlift or not to weightlift?

That is the question. My answer? It depends.

I encourage coaches to look at the bigger picture. Does the athlete have enough time to learn the technicalities of the lifts? Are the athlete’s movement patterns proficient enough? Does the athlete have enough weight-room experience? Are there any severe mobility or stability issues that the athlete has to address beforehand? Are the alternatives sufficient for the time being? There is more than one route to achieve ideal athletic qualities. The factors that set apart good and bad S&C programs from each others are the risk to reward ratio, efficiency and specificity.

References

Suchomel, T. J., & Sole, C. J. (2017, September 1). Power-Time Curve Comparison between Weightlifting Derivatives. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5592293/

Shattock, K. (2018, February). The Use of Olympic Lifts and Their Derivatives to Enhance Athletic / Sporting Performance: A Mental Model. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322901416_The_Use_of_Olympic_Lifts_and_Their_Derivatives_to_Enhance_Athletic_Sporting_Performance_A_Mental_Model

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JASON LAU is a Strength & Conditioning / Physical Preparation coach and owner of PERFORMANCE PURPOSE based out of Richmond, BC. His passions include coaching and refining badminton, volleyball and hockey athletes, beginner to provincial level powerlifters, return-to-play rehab and general population clientele of all ages.

He aims to offer a systematic and evidence based approach to off-season and in-season training, translating the athlete’s weight room progress towards their specialized sport. His goal is to drive improvement and progress of each individual within the field of athletic performance.

Website: https://performancepurpose.ca/

Instagram: @performancepurpose

Optimizing The Warm-Up Using RAMP & Mobility Flows

The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

Its the general consensus that a warm-up is a mandatory component of any training session, no matter what sport or athlete you’re working with. The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

As a result of poor practices in the past, as well as noticing trends in the high-performance world, I remain unconvinced on the concept of needing to perform an overabundance of exercises to “activate” muscles or “mobilize” the joints prior to training. Banded distractions, foam rolling, all the bullshit that people waste their time on because “that’s how everyone else does it in the industry”.

I was unsatisfied and baffled over the fact that a warm-up could potentially take up 25% of the time out of a training session. The warm-up is the low hanging fruit in terms of programming improvements. Simple changes to the warm-up protocol afford coaches and athletes more time to put into more meaningful training that develops athletic performance.

Out of a necessity to make my personal coaching sessions run in a more smooth and efficient manner, I’ve created a mobility flow warm-up as a way to address the first 3 letters of RAMP within one series of exercises.

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

(R)aise body temperature

(A)ctivate muscles

(M)obilize joints

(P)otentiate to reach intensities seen in the training program

In this mobility flow, I’ve sequenced multiple foundational movement patterns together such as squatting, hinging, lunges, pressing and rotating. Alongside the obvious rise in body temperature from performing this, the emphasis on large range of motion movements and anti-rotational positions addresses both the “activation” and “mobilization” aspects of a warm-up, saving time that can be put into actual, meaningful training.

While this mobility is ground-based and has a lot more potential for additional exercises, the principles I work with remain the same - achieve rise in body temperature, put muscles and joints through a large range of motion and improve proprioception as quick as possible. Modify this flow as you see it fits your training demands.

After the mobility flow, some sort of potentiating training follows in order to reach the intensities seen in the training session (whether the session is strength-based, plyometric-based or concurrent). More details about exercise order and potentiation can be found in my exercise order article.

Application

This mobility flow can be performed as a warm-up, as a cooldown, or as an active recovery protocol.

Warm Up: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Cooldown: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Active Recovery Protocol: Multiple sets of 3-5 minutes, or one long set of 15-30 minutes (Keeping HR in Training Zones 1 and 2)

Great response from my athletes so far. Will be refining this over the next few months. I hope you enjoy it.

[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball

In the world of performance training, a needs analysis of the sport is mandatory—but this only represents the first step to a fully optimized training program. Not all athletes of the same position will have the same playing style, and understanding this is important for designing and coaching a training program to optimize performance and injury mitigation.

In the world of performance training, a needs analysis of the sport is mandatory—but this only represents the first step to a fully optimized training program. A coach must also look at the playing style of the individual athlete and the demands the athlete puts on their body to be successful on the court. Not all athletes of the same position will have the same playing style, and understanding this is important for designing and coaching a training program to optimize performance and injury mitigation.

This article features a case study on Darryl Wong to show the inner workings of a performance training program for a basketball athlete.

READ MORE @ SIMPLIFASTER [CLICK HERE FOR THE ARTICLE LINK]

[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Plyometric Push-Ups and Progressions for Power Development

Push-ups are one of the most commonly used exercises among fitness buffs and elite-level athletes. As a closed-chained exercise that targets the chest and upper body musculature, push-ups are highly effective for improving upper body pushing strength and endurance, and can be done with no equipment.

Push-ups are one of the most commonly used exercises among fitness buffs and elite-level athletes. As a closed-chained exercise that targets the chest and upper body musculature, push-ups are highly effective for improving upper body pushing strength and endurance, and can be done with no equipment. There are plenty of regressions, progressions, and variations to pick from, making push-ups useful for athletes of all types. From bodyweight push-ups to loaded isometric push-ups, there are also various ways to load and challenge the movement...

[Read More @ SimpliFaster.com - Click Here For The Link]

Powerlifting Performance - 3 Commonly Neglected Areas

Having coached many competitive powerlifters for the last 3-4 years, I've noticed common areas in the realm of training and recovery that many strength athletes neglect. Either the importance of these areas have not been stressed enough by their coaches and the environment they lift in, or the athletes fail to see the impact it plays on their powerlifting performance.

GCPT Powerlifter: Wendy Yamazaki @ BCPA Provincials 2017

Having coached many competitive powerlifters for the last 4-5 years, I've noticed common areas in the realm of training and recovery that many athletes (especially beginners and intermediates) neglect. In the past, I've written about how athletes coming into powerlifting should treat it like a sport and focus on a more well-rounded approach to athletic development. This means including a wider variety of exercises into one's training program, and covering foundational bases such as work capacity and recovery capabilities before progressing onto high-frequency and highly-specific powerlifting programs.

This article will expand on few of those details by highlighting the 3 most neglected areas of training and recovery I see in athletes of all levels. Either the importance of these areas have not been stressed enough by their coaches and the environment they lift in, or the athletes fail to see the impact it plays on their powerlifting performance. These tips will benefit everyone from the beginners, to the most elite athletes.

#1 Work Capacity and General Endurance

The number one goal of any beginner powerlifter is to improve work capacity and general endurance. Being able to handle higher volumes of work will be lead to faster technical improvements, more muscle hypertrophy and higher recovery capabilities; 3 important areas that are crucial for building maximum strength in powerlifting.

An interesting observation I've made over the last few years, is that female lifters I've coached have a higher tolerance for volume, and as a consequence, improve their powerlifting technique at a much faster rate than men. The higher capacity for recovery in between sets and the ability to perform more repetitions without fatigue means more quality time under the bar - leading to faster learning. This might be because females tend to have a different training background than men before starting powerlifting, performing more circuit-based training and more dedicated cardio sessions throughout their powerlifting programs.

Regardless of your training background, what can you do to improve work capacity and recovery capabilities in the realm of powerlifting?

Higher Rep Sets - the most common way is to perform higher rep sets (8-12+ reps per set) for multiple mesocycles (weeks/months). Stay calm, and don't rush through the set - this will teach you how to breathe properly and build a higher tolerance to higher heart rates and lactic acid/lactate build up.

Increase Training Density - Training density refers to the volume of work done within a certain time period. To increase training density, simply do more work in less time. You can achieve this by reducing the rest times in between sets, or set a time limit/goal for finishing your workout. Other methods include super setting your accessory exercises or performing some form of active rest in between sets. This will also take away the fluff from your training sessions: talking to your friends for too long, getting side tracked with music selection, etc. Anything that may be considered a distraction.

Active Rest Days - Most novice powerlifting programs consist of 3-4 hard training days. That leaves another 3-4 days that can be dedicated to improving other physical attributes. This is where active rest days come in. The most common forms of active rest include mobility/range of motion training and low intensity steady state cardio (go for a walk, go for a bike ride, go for a swim). The point here is to keep the blood flowing, keep the muscles and joints warm without interfering with the recovery process of powerlifting. Low impact, low intensity cardiovascular training is a great way to build a strong aerobic system responsible for your recovery capabilities between sets and between training sessions.

Prime Your Mindset For Higher Effort Work - Don't fall into the trap of "powerlifters don't do cardio". This is something I bring up time and time again: don't allow the destructive culture of demonizing cardiovascular training in strength sports to hinder your progress and athletic development. Embrace the volume, treat yourself like a well-rounded athlete.

2. Accessory Work - Attention To Detail

Powerlifters spend A LOT of time and effort making incremental improvements to their sport-specific lifts. Grip and stance width, leverages, joint and torso angles, internal and external cues; these are all modifiable components of the powerlifts that are experimented with in order to produce the heaviest, most efficient lift possible. However, accessory work often becomes an afterthought and the technical demands of those exercises are often neglected.

My philosophy for powerlifting performance is to put the same amount of effort into the accessory work as you do the competition lifts. If an accessory exercise is supposedly prescribed to address the weaknesses of a powerlifter such as strengthening a certain range of motion on a particular competition lift, or strengthening a particular muscle, technique on the accessory work must be held to a higher standard. Powerlifting for me is not only about the squat, bench press, and deadlift, but also about building physical literacy - knowing your way around your own body. The athletes that perform pull ups, lunges, and other movement patterns with a higher proficiency get MORE out of the exercises than those who don't. Great lifters maximizing the transfer effect of accessory exercises. 4 sets of 10 reps done with a full range of motion with the right joint and muscle angles beat 4x10 done with poor form; despite the volume load being the same on paper. Accessory work done with focus and intent transfers more to powerlifting performance then accessory work performed half-asses or with poor technique.

When you're considered an intermediate athlete, that's when glaring weaknesses start to show and you have to start addressing them. Don't get lazy, search up some Youtube videos of proper form just as you would with the powerlifts. Pay attention to the details.

3. Sleep

Before supplements, ice baths, sauna sessions, and mobility routines were all the hype, there was sleep. Sleep is the greatest recovery modality and is the primary form of recovery you should be optimizing and focusing on.

I use a monitor/diary to keep track of my athlete's readiness and recovery and I've noticed a big correlation between low scores on sleep quality (2 to 3 out of 5) and poor training performance. Athlete's that consistently measure lower than 3 out of 5 on "Sleep Quality" record higher rates of perceived exertion (RPEs) per any given % of their 1RM and progress at a slower rate week to week. A lack of sleep or poor sleep quality cascades into higher stress levels throughout the day, more incidences of bad mood/irritability and can negatively affect an athlete's focus during training and everyday activities.

Here are some general recommendations to improve your sleeping quality and duration from years of experimenting and reading about sleep:

Aim for 7-8 hours+ of sleep (everyone probably knows this one)

Keep a consistent wake-sleep schedule

Sleep in a comfortably cold, quiet and dark room, this is an important tip for those who find themselves waking up frequently in the middle of the night

Considering using aids such as an air humidifier, ear plugs or eye mask/blindfold to improve sleep quality

Avoid drinking large volumes of liquid/water before bed if you find yourself waking up several times in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom

Turn off electronic devices 1-2 hours before bed (something I struggle with, god damn Reddit...)

An alternative is to use a screen dimming app or an app that removes the bluelight from your devices (f.lux for Windows & iOS, Twilight for Android devices)

Avoid caffeine consumption close to bed time (can affect people up to 6 hours between caffeine consumption and sleep)

Practice good napping habits - this has shown to be beneficial for recovery and future performance

Consider supplements like ZMA, Vitamin D, Melatonin and even Cannabis to improve your sleep quality (if legal in your state/province/country).

Consider using a Sleep Tracking app which can promote higher quality sleep by making you more conscious about your sleep habits.

Below is a list of articles/podcasts/infographics that may help you:

"The Importance Of Sleep Quality and How To Improve It" - Examine.com

"Can Supplemental Vitamin D Improve Sleep?" - Examine.com

"Sleep Better: Practical Evidence-Based Recommendations" - Amy Bender on Sigma Nutrition Radio

"Recovery & Performance In Sport Infographics" - YLM Sports

No intricate periodizational methods or detailed technical breakdowns here, just foundational aspects of training and nutrition that I think are crucial for the long-term success of any strength athlete. Don't be afraid of performing training modalities outside of the big 3 lifts, and when you do, approach them with the same standard you would the competition lifts. Sleep well, eat well, train hard and recover harder.

The Science of Core Training: Training Methods & Application (Part 2 of Core Training Series)

Part 2 of this core stiffness article series will cover the core training principles and methods that drive short and long-term improvements in performance.

Read Part 1 Here

In part 1, I went over what the core is and the function of core stiffness in relation to sporting performance and optimal force and power output. To recap: core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed.

Highly recommend reading part 1 before continuing on with this article.

In part 1, I mentioned that improving performance via increased core stiffness will depend on multiple variables:

The nature of the sport and the energy systems involved (How long is the core braced for? Does the athlete need more strength? Or more endurance?)

The particular movement you're trying to improve by increasing core stiffness

The properties of the movement itself and the speed of core stiffening

The magnitude of core stiffening (stiffer doesn't always mean better, remember: fast and powerful athletes also need to learn how to relax at the right times - like the example of the punches and kicks we used earlier).

First off, I'd like to break this article up into 2 categories, short-term improvements in core stiffness and long-term improvements in core stiffness.

SHORT-TERM IMPROVEMENTS

Short-term improvements or increases in core stiffness, are characterized by improvements seen within the same training session. Known and performed as "core activation" drills among personal training circles, some claim that performing core exercises prior to the main exercises of a workout "wakes up" the core and improves performance on the subsequent exercises. While terms like "wake up" are very arbitrary, it helps to look a potential mechanism by which core activation drills help with short term performance.

Post Activation Potential

Benjamin Lee and Stuart McGill carried out a study in 2017 to measure the effects of short-term isometric training on core torso stiffness and found beneficial results. For the core isometric training protocol, participants performed the plank, side plank and bird dog exercises for 5 sets of 10 seconds - with coaching cues being offered and standardized to all participants. Using both passive and active torso bending trials, the results showed that most participants had reductions in torso deflection and increased core stiffness (more details here).

While this study showed that short-term core stiffness can be increased via isometric core exercises, it doesn't tell us how that core stiffness will transfer to performance in other exercises, or how long this effect lasts. In their discussion, the authors pointed to the fact that the isometric exercises done could have elicited a post activation potential (PAP).

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where strength and rate of force development (power) is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. The most common protocols may include heavy back squats to elicit a PAP effect before sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses before performing ballistic medicine ball pushes/throws. Utilizing the PAP effect is also known as complex training. Here are some examples of exercise pairings, from the NSCA.

Taken from https://www.nsca.com/Education/Articles/Hot-Topic-Post-Activation-Potentiation-%28PAP%29/

For a concise explanation of the potential mechanisms behind PAP and how it works, visit Science For Sport.

Back to the study. While the authors pointed out the PAP mechanism, they acknowledged that their core training protocol, despite improving core stiffness, did not meet the requirements of a "potentiating exercise". In a standard PAP protocol, the potentiating exercise has to be close to max effort, with the recovery time reflecting the nature of exercise. Lee & McGill's (2017) study's core training protocol included 5 sets of non-fatiguing core exercises (only 10 seconds long - bodyweight, no added resistance), so I'd be interested to see if there could be a larger PAP effect if some core exercises are taken to near max effort. Here are some ideas:

Complex Training For Core & Power Exercises

Weighted Planks into Medicine Ball Slams (2-3 minute recovery)

(3-6 complex sets of <30sec weighted planks into 4-8 max effort slams)

Planks are one of the most frequently prescribed core exercises in the fitness and strength training. An easy way to increase the difficulty of the plank is to add extra resistance - perform them weighted. In this complex set, the weighted planks act as the potentiating exercise, increasing the the power output of the slams. While the effort should still be high during the planks, the physiological stress is relatively low compared to for example, a set of heavy front squats; meaning the recovery time should be lower than most heavy compound movements. A recovery time of 2 minutes should be adequate before performing the medicine ball slams.

Squatted Pallof Press Into Rotational Medicine Ball Slams/Throws (1-2 minute recovery)

(3-6 complex sets of 6-8 presses into 4-8 max effort slams/throws)

In this example, I use an anti-rotation exercise to potentiate a ballistic exercise for better power transfer. I also added a small rotation component to what would normally be an anti-rotation exercise (the pallof press) to mimic some of the movements seen in the medicine ball rotation throw. Keep in mind, I still maintain tension on my obliques working and the shoulder girdle stable during the press out and rotation. Recovery time can be anywhere from 1 to 2 minutes.

Other Potential Ideas

Core Stiffness For Powerlifting

Aside from using higher effort complex sets, I have found situations where non-fatiguing core exercises can help improve the quality of a training session. For the last couple of months, I've been using bodyweight planks and shorter weighted plank sets with my powerlifters prior to the main compound lifts . Planks are a good way to emphasize whole body tension (a skill that is required for powerlifting success), to improve the lifters' perception on how active their core for the rest of the training session, and to remind them about the importance of a rigid torso during the powerlifts. Most, if not all of my powerlifters, have found this pre-lifting core work beneficial.

With this protocol, perform several sets of planks at a low RPE (non-fatiguing) to avoid overly fatiguing the core musculature before the compound lifts. More advanced trainees can experiment with planks at higher intensities to elicit a greater PAP response. Slowly increase the intensity of these planks over time to find the sweet spot (balance of volume and intensity).

Core Stiffness For Weightlifting

Another idea I've implemented in the past is the use of higher velocity core stiffening drills to help facilitate weightlifting technique improvements. The catch position of snatches and cleans require a lifter to quickly decelerate the weight by using the prime movers and stiffening the core upon bar contact. I've found depth drop landings or plyometric regression exercises to help with this. Here's a quick example with one of my Strongman/Powerlifting athletes, who was brand new to the Olympic lifts at the time. Used in conjunction with other coaching techniques, he made some good improvements just over the span of 3 months.

Intra-abdominal Pressure (IAP)

If you've spent anytime studying strength training or have spent time in the weight room, you probably heard of the concept of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). Also referred to as "bracing", intra-abdominal pressure is a technique by which a trainee creates 360 degree pressure in the abdominal cavity through controlled inhalation. The created pressure helps stabilize the lumbar spine, reduce the risk of back injuries as well as improve force output. The concepts of core stiffening and creating intra-abdominal pressure are complimentary and much like the core stiffening concepts discussed previously, IAP is not an all or nothing phenomenon.

IAP happens on a continuum, and can vary in intensity and duration depending on the movement requirements of the task. Coaches around the world all stress the idea of creating IAP during strength training, however, not many of them can explain it as well as Chris Duffin (Kabuki Strength) and Stuart McGill. Kabuki Strength describes IAP as a continuum of respiration (breathing) and stabilization (max effort IAP), best represented by a dial.

To give an example, the lumbar stability needs during a 1RM compound lift is different than a sub-maximal activity like running. Running requires just enough IAP to stabilize the torso, while still allowing for optimal breathing. Turn the knob accordingly.

““Improving your ability to select and coordinate the correct dial setting is the key for fluid movement and higher performance in any activity””

long-term improvements

Long-term improvements in core stiffness are characterized by improvements seen over weeks and months of core training. This section will cover the different categories of core training, as well as general training principles that drive long term improvements.

Core Training Categorization

To start, it's best to differentiate between core exercises in order to better analyze their cost-to-benefit ratio. All exercises fall on a general to specific continuum, with the reference points being the movement you want to improve, or the sport/position you're playing - core exercises are no different. Dedicated core exercises can be broken down into several categories:

1. Isometric Core Exercises

Isometric exercises are exercises where force is produced without a change in muscle length. Exercises like planks and hanging L-Sit where you're maintaining your body position are examples of isometric core exercises.

2. Anti-Rotational Core Exercises

Anti-Rotational exercises also fall the "isometric" category. These exercises challenge your ability to stabilize your body to prevent from rotating to any one side, maintaining your body position against an external force or in an imbalanced position. Common exercises include the pallof press, shoulder taps in push up position and many exercises in the half kneeling position. Other great examples not many people know about could be suitcase deadlifts, and uneven farmers walks (videos below).

3. Isotonic Core Exercises (Sagital Plane/Transvere Plane)

Isotonic exercises are exercises that consist of an eccentric and concentric portion - exercises that are not isometric (holds). They can be further broken down into sagital/transverse plane exercises. Sagital plane exercises include standing cable crunches, sit ups and hanging leg raises, while transverse plane exercises involves any exercise that involve torso rotation like cable wood-choppers and medicine ball russian twists.

4. Ballistic and Plyometric Core Exercises

Ballistic exercises are concentric-dominant power movements with little to no eccentric muscle action, such as jump squats and explosive push ups. In the realm of core exercises, medicine ball slams, rotational throws can be considered ballistic, but keep in mind the prime movers such as the shoulders and glutes also contribute to the force output.

Plyometric exercises are exercises with a short eccentric-concentric turnover, using the elastic properties of our muscles to improve speed and repeated power output. Many movements like running, repeated jumps/hops and combination striking (in martial arts) are considered plyometric. There are also plyometric exercises designed just to target the core musculature - many of these being rotational. I've posted a few examples below:

Taken from Nick Curson (Speed of Sport)

Taken from Elliot Hulse

Training principles and methods To Improve Performance

Conversations usually go south whenever the topic of "transfer to performance" is brought up; there are many complex variables to take into consideration and everyone seems to have their own definition of "functional" or what exercises will and will not help improve performance. I'll be giving some general tips and training principles of core training that can be applied to various different sports.

Post-activation-potentiation, non-fatiguing core primers and intra-abdominal pressure are all acute techniques that CAN lead to long-term improvements

The research is still not conclusive on whether these are significantly beneficial, but in theory: accumulating small short-term improvements should lead to long term improvements in performance. In other words, if these techniques are performed consistently throughout your training program, they may add up to a measurable increase in strength, power and endurance (whatever you're aiming for). I would also add that the use of PAP and core primers are optional, but in my opinion, IAP is not. I consider IAP a skill that must be learned and utilized consistently in order to effectively produce force, and stay safe doing so.

A combination of general and specific core exercises should be performed

Don't fall into the "functional" trap of prescribing overly-specific exercises. A general exercise that does not fully mimic the movement you're trying to improve can still be beneficial. For example, weighted planks are a great general core exercise to build core strength and endurance that will transfer over to various movements. Once a good base is built, you can start experimenting with more specific exercises. I've included some examples of specific exercises at the end of this article, mainly geared towards improving punch power, but can also be used as core training.

To learn more about the general-specific continuum and how to classify exercises for better training prescription, read my article I wrote on training variation here.

Principle of progressive overload

This is the premise behind improving any type of performance measure. Progressive overloading your core exercises either through a change in position, adding extra resistance, increasing the volume via sets, reps or time. In order to improve, you must progressively add stress to your physiological system, recover from it, and come back stronger.

Improving Core Strength (Slow-Isometric Stiffness)

Core strength, or slower-isometric type core stiffness, is primarily built using isometric and anti-rotation based exercises. Almost every core exercise listed above can be used to improve core strength, but what differentiates training core strength from core endurance is the intensity at which these exercises are performed. Reps should be done in the lower rep range (~<6 reps per set) or 80-95% of 1RM if a 1RM is applicable. Accordingly, intensity/weight progression is what you should be focused on. For example, progressively working towards heavier weighted planks (increasing intensity) instead of increasing the time of which you hold body-weight planks. Improving core strength will benefit every athlete, but strength and power athletes will see the best results.

Improving Core Ballistic/Plyometric/Power Ability (Fast-Recruiment Stiffness)

Core plyometric ability, or what I like to describe as a faster-recruitment type core stiffness, is built through plyometric core exercises and have a higher skill/timing component to it. This is the type of core stiffness I discussed in part 1, that is required for high-impact athletes who perform punching, kicking and striking movements. The ability to contract-relax-contract and produce a fast eccentric-concentric turnover is what defines an athlete with good core power and plyometric ability - both deceleration and acceleration are taken into account.

I gave examples of relatively advanced plyometric core training above (see Nick Curson and Elliot Hulse's videos). A more beginner friendly way to perform these exercises would be to reduce the range of motion on the exercises and reduce the power output until you improve your timing. A drill I found useful are short plyometric medicine ball rotation slams - timing and rhythm are paramount here so develop them before moving onto higher-intensity, higher-effort plyometrics.

Improving Core Endurance

When people think of the word "endurance" they immediately associate that with a low-intensity, long duration training protocol. Don't make the same mistake. Endurance can refer to the ability to maintain a certain power output for an extended period of time OR be able to repeatedly perform high-intensity bouts with little to no drop off in power output from start to finish. I recommend using work-to-rest ratios with your core exercises based on the energy system you want to develop.

Do you want to be able to repeat maximal high-intensity efforts? Use work rest ratios anywhere from 1:20 to 1:30+. For example, 6 seconds of maximum effort tornado ball slams with 2 minutes of complete rest in between sets, for several sets (1:20 work-rest ratio).

Looking to improve anaerobic capacity? Use work-rest ratios around 1:1. For example, 60 seconds of moderately heavy farmers walks with 60 seconds of active rest in between sets (1:1 work-rest ratio).

Looking for longer duration core endurance? Perform lower intensity core exercises for a total of 3 minutes+ at a time with a work-rest ratio of ~2:1. For example, hold a bodyweight plank for sets of 3 minutes with 1.5 minute rests in between. To add some variation to these longer sets, you can also perform 3-4 different core exercises as a circuit for 1 minute each. Over time, increase the duration of each set or the total number of sets (volume load progression at a set intensity).

Using work-to-rest ratios is another tool by which you can use to look at and utilize core training with. It can help you visualize which energy systems are at play, so you can make the adaptations you want to see. Endurance is specific.

Diminishing Returns

More core work means better performance right? Not so fast. Welcome to the principle of diminishing returns. The more you train core stiffness, the less benefits you reap in. I see core stiffness training a lot like maximal strength for sports. There comes a point where more core training does not equate to better performance on the field, court, platform or ring. Core stiffness, much like strength, serves as a foundation on which other important physical attributes are built on - rate of force development, agility, resilience to injury to name a few. Be careful not to allocate all of your time and energy into core stiffness training, while neglecting the development of other skills and attributes.

So how much is enough?

Unfortunately, I don't have a concrete answer for you. This really depends on what sport and movement patterns you're referring to. Core training should fill the gaps of your physical development, and be used in conjunction with sport-specific skill work and strength/power/plyometric training. Being able to competently perform all the movement patterns and core exercise categories listed above is a great start.

Biggest takeaway

If there's one thing you take away from this article, it's that core stiffness training is context-specific and should be thoughtfully prescribed and developed. Core training does not have to be boring, so don't be afraid to get creative. Below is some of my content I've put out on core training, core ballistic training and various medicine ball slam exercises. Thanks for reading!

ARTICLE: Great Core Exercises You're Not Doing

CORE TRAINING VIDEOS:

The Science of Core Training: Core Stiffness & Performance Overview (Part 1 of Core Training Series)

This article will overview the concept of core stiffness and how it's applied to several sporting performances and movements. Core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed.

Core training has been all the hype the last several years - from an aesthetic point of view (achieving 6 pack abs) to it's potential role in reducing lower back pain and related symptoms. This article won't be touching on any of those points. I'm speaking more from a performance-enhancement perspective, specifically, the role of core stiffness and it's relation to performance outcomes.

What is the "core"?

The musculature and structures between your shoulder girdle and your hip; the superficial and deep abdominal muscles.

What is the function of the "core" and what is "core stiffness"?

Ask a performance coach and they'll give you one answer. Ask a physical therapist and they might give you a different one. From a physical therapy or rehabilitation setting, core stiffness may refer to increased muscle tone that leads to lower back pain and movement restrictions. In the performance sports setting, core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed. For the purpose of this write up, I'll be talking about the latter.

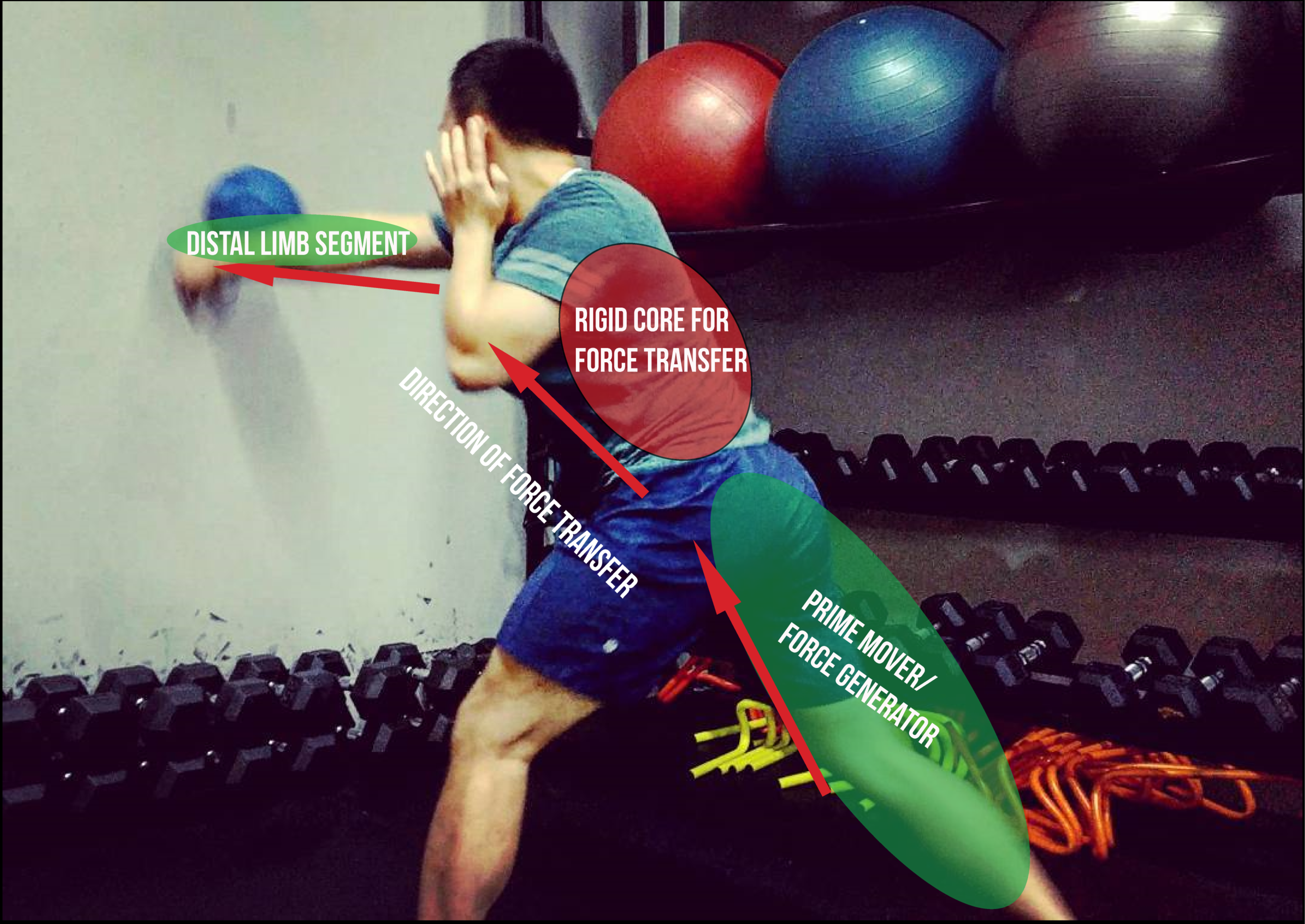

To my knowledge, the function of the core is to transmit force, prevent force/power leaks and maintain the position of certain joints and body segments. In the words of professional lower back and spine expert Stuart McGill, he describes the function of the core to "stiffen the torso to prevent motion, [and] enhance motion of the distal limb segments".

In the majority of sporting performances, the ability to accelerate distal limbs is the key to high power output: think about throwing a baseball, kicking a soccer ball, jumping, pushing, punching. Stiffening the torso to prevent excessive motion and enhances force production and power output because it acts as a medium for force transmission - ensuring all the force you generated is directed towards your intended direction. A floppy and weak midsection results in a weak kick, a weak throw, a weak jump and a weak landing.

an overview, with examples.

The idea of core stiffness allowing for better force production/transfer can be applied to many different scenarios. I'll give 3 examples from 3 different sporting types, a mixed sport (Mixed martial arts/combat sports), an endurance-dominant sport (Cycling) and a strength-dominant sport (Powerlifting).

In each example, the RED highlighted area represents the "core": the superficial abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis), the deeper muscles like the transverse abdominis as well as surround muscles like the obliques (for rotation), latissimus dorsi and rotator cuff muscles.

The GREEN highlighted areas represent the prime movers that are responsible for generating force through concentric muscle action, and/or the distal limb segments that are used to transmit force into the intended direction or to move a certain object.

Example #1 - The Punch and Kick in Martial Arts

The straight right/left punch is one of the most basic, yet intricate techniques in martial arts. Contrary to what many think, the prime movers of the straight punch are actually the back leg, the muscles surrounding the hip and the shoulder girdle, NOT the arms. Power is generated by pushing off the back foot, contracting the glute, and directing that force into the distal limb segment (which is the fist in this scenario).

In order to effectively transmit that power from foot to fist, the core must rigid. The obliques must create enough deceleration force to prevent your torso from over-rotating (shifting you off balance), and your shoulder girdle must be sturdy enough so loosen up on impact. Additional, these types of movements (punches, kicks, hitting/impact-movements) exhibit a "double peak" in regards to muscle activity (measured through Electromyography (EMG)). In other words, whenever performing a powerful movement, the muscles will go through 3 phases: contract/stiffen, relax, and contract/stiffen once again upon impact, showing a "double" peak in activation (will be pictured below).

Stuart McGill et al. performed a study in 2010 on elite mixed martial artists (Georges St. Pierre, David Loiseau to name a few) that introduced me to this concept so I'm sure he can explain it more clearly:

“Many of the

strikes intend to create fast motion and finish with a very large

striking force, demonstrating a ‘‘double peak’’ of muscle activity.

An initial peak was timed with the initiation of motion

presumably to enhance stiffness and stability through the body

before motion. This appeared to create an inertial mass in the

large ‘‘core’’ for limb muscles to ‘‘pry’’ against to initiate limb

motion. Then, some muscles underwent a relaxation phase as

speed of limb motion increased. A second peak was observed

upon contact with the opponent (heavy bag). It was postulated

that this would increase stiffness through the body linkage,

resulting in a higher effective mass behind the strike and likely

a higher strike force.”

To further illustrate the "double peak" in activation, and to tie it back to the discussion earlier about prime movers and the core, here's a figure taken from McGill et al's 2010 study (green and red highlights made by myself).

This figure illustrates the muscle activation of the left back muscles during a left leg kick to a heavy bag.

Taken from McGill et al. 2010

#1 in green represents the initial activation of the muscle (phase 1 - contraction), where the foot pushes off the floor and the hip flexors and obliques contract in order for the leg to be lifted into the air. The prime movers are the hip, quadriceps and left back.

#2 in red represents the relaxation phase (phase 2) where the leg is in mid air and force is being transmitted through the core, to hit the intended target (shin/foot hitting the heavy bag).

#3 in green represents the second activation of the muscle (phase 3 - contraction again), where the muscles stiffen up once again on impact.

An athlete with a weak core, or an inability to stiffen up the core will experience power leaks in #2, which subsequently results in a lower striking force upon impact in #3.

Optimal force and power production happens when an athlete has:

Good body positioning

The ability to show double activation during strikes/impact movements

The ability to efficiently cycle through contract-relax-contract muscle action if repeated punches/kicks/impacts are performed

Strong and resilient core musculature.

Example #2 - cycling

Operating at up to 300RPM (revolutions per minute) and putting out up to 2,200 watts, track cyclists are known for their lower limb strength and power, as well as their ability to maintain extremely high power outputs for extended periods of time.

Watch the video below, notice the rigid and stable core - supported by the shoulders and arms, and how that translates to incredibly fast distal limb segment movement (in this case, the feet).

Yes, the thigh musculature are still the primary movers, but the core/torso also contribute greatly, acting like a shock absorber to negate most of the horizontal and vertical bodyweight shifting that happens during high RPMs. A strong core ensures as much of the force generated by the prime movers can be directed towards spinning the pedal.

Picture taken from TeamNater (Youtube), editted by myself.

The principles of contract-relax-contract discussed above also apply to this example. The quadricep has to relax while the hamstring is active during the (pedal) upstroke, and vice versa during the downstroke. Pair it with the fact that this is all happening at 150, 200, 250+ RPM and you'll realize the amount of motor control needed to be an elite cyclist.

Example #3 - Powerlifting

Our last example is a strength sport - powerlifting. Powerlifting is a maximal strength sport, meaning the velocity of distal limbs and the velocity of the bar is relatively low compared to other sports such as Olympic Lifting or various throwing sports. As a result, core stiffness plays a slightly different role - a slower isometric role. Although there is no contract-relax-contract cycle in powerlifting, the core still acts as a stopper for potential force leakages. The main role of the having a rigid torso/core is to support the lumbar and thoracic spine under heavy load.

In a sport where limb length and leverages are highly influential on performance outcomes, a lifter must maintain the position of their lumbar and thoracic spine so that their chest does not collapse under the weight, and their lower back doesn't go into excessive flexion. Losing position means the lifter will not be able to lift the weight up, regardless of how strong their prime movers are.

Below is an example of one of the lifters on my Powerlifting team, Amos So, bracing for a squat at a local powerlifting meet.

Context Specific

Throughout the article, I've used terms like "stable", "rigid", "strong" and "resilient" to describe the properties of a well-functioning core. Different coaches and trainers will use different terms to describe the core, so terminology is sometimes confusing.

However, what matters is how you apply these principles to your own training, or the training of your clients and athletes. Improving performance measures via increased core stiffness will depend on several things:

The nature of the sport and the energy systems involved (How long is the core braced for? Does the athlete need more strength? Or more endurance?)

The particular movement you're trying to improve by increasing core stiffness

The properties of the movement itself and the speed of core stiffening

The magnitude of core stiffening (stiffer doesn't always mean better, remember: fast and powerful athletes also need to learn how to relax at the right times - like the example of the punches and kicks we used earlier).

Much like the development of max strength for athletic performance, there are also most likely diminishing returns, so don't fall into the trap of "more core training = higher performance".

In part 2 of this series, I'll be explaining the different methods to improve core stiffness in the short-term and in the long-term.

Read Part 2 Here.

Thanks for reading, feel free to share this article with your peers and fellow coaches. Also, please check out my social media links and reach out to me if you have any questions or suggestions.

The Building Blocks of Powerlifting Performance

First off, what is base building? It's a term I like to use to describe the rudimentary steps a beginner or intermediate strength athlete has to take in order to become successful 1, 3, or even 10 years down the road.

A few of the powerlifters I coach have just finished competing this month at BCPA Provincials and many are entering their so-called "off-season", so I thought I would take this time to talk about base building in powerlifting. First off, what is base building? It's a term I like to use to describe the rudimentary steps a beginner or intermediate strength athlete has to take in order to become successful 1, 3, or even 10 years down the road. Think of it as a pyramid, widening the base to support a much higher peak. It can also be applicable for lifters that may have not had the best competition cycle and need to go back to the drawing board to improve their training.

So in practice, what does it mean to build or widen your base?

It means putting conscious effort into investing in proper technique acquisition and developing the right habits and mindset for you to excel in your athletic career. In my mind, there are 3 things that must be addressed to create an environment where you reap in the most benefits from your training. Technical mastery, habits and consistency, and mindset.

Technical Mastery In Powerlifting

“Practice does not make perfect. Only perfect practice makes perfect.”

In a closed-skill sport like powerlifting that does not depend on anyone else except for yourself and the bar, technical perfection is more in-reach than many other sports. Unfortunately, the ego often gets in the way, causing some people to lift with brutally poor form until they get injured or hit a plateau. If injury or a high risk of plateauing doesn't scare you off, I don't know what will!

I used to be an advocate of performing the competition lifts (Squat, Pause Bench Press, Deadlift) once a week if you were a beginner. My train of thought was, save the higher frequency competition lifts for when you become stronger and enter your intermediate/advanced stages. Performing the competition lifts 1x a week was a common recommendation, but it seemed to always come from experienced, drug-enhanced lifters, who were able to fit in much more training volume within any given session and recover much faster than natural athletes.

Fast forward to today, I'm a big believer that training the competition lifts more frequently makes more sense because it is in line with the principle of specificity, and can be done when fatigue is managed.

Competition lift frequency - more is better

Exposing a beginner to the competition lifts 1x a week is just not enough practice. With my athletes, I prescribe a minimum 2x a week squatting, 2x a week benching and 1x a week deadlifting with an additional hip hinge movement on another day - preferably another barbell deadlift variation like a Romanian deadlift. While this may seem overwhelming for a beginner, it can be done if intensity and effort is controlled.

The first session will be focused on high effort work, where sets are in the 8-9 RPE range. The second competition lift session must be dialed back to a 5-7 RPE range depending on the experience level of the athlete. Any of the programming variables (sets, reps, intensity) can be rearranged, but the theme is to reduce the effort - essentially making it an "easy" day.

A higher frequency of exposure and performing more reps per week will benefit motor learning.

Technical improvements can be made in the absence of high intensity and effort, simply exposing the athlete to the competition lifts 1 more time a week, can do wonders. Squatting, benching and deadlifting once a week can still be beneficial for general strength training. However, if you're an aspiring powerlifter, consider increasing the frequency for faster learning.

Even intermediate or more experienced lifters aren't necessarily exempt from base building. If you're struggling to make technical improvements, read this write up I did on improving technique and the idea of using a technical breakdown threshold (TBT), which is more geared towards experienced lifters.

Consistency

“First we make our habits, and then our habits make us.”

You'll often hear adherence and consistency is everything. The most complex training programs will yield no results if you're not consistent with your training. Showing up to training sessions, completing training within a certain time frame, maintaining focus, good form and technique throughout the session, consistently consuming enough protein and calories.

In order to build successful lifting habits, you must create an environment where you can be consistent.

Consistency in regards to training frequency is one thing I want to talk about in particular. When deciding a training frequency (3 lifting sessions a week vs. 4x, 5x..), be conservative and pick the lowest one you're 100% sure you can maintain for the training cycle.

If you're on the edge about whether you should train 4x a week or 5x a week, pick 4x a week. Programs are designed to spread out training volume given a set training frequency. If you know your work schedule or other life commitments might get in the way of your training, missing a training session every week or other week can add up. You would be essentially missing a chunk of training load that could have been better distributed had you picked a training frequency of 4x a week. While a coach can modify training volume on the week-to-week basis, not all lifters have this luxury or access to a competent coach.

Mindset & persistence

What brings programming variables, technical mastery and consistency together? Mindset and persistence.

Elite-level strength acquisition takes a long time.

There will likely be someone stronger than you.

Training is not life.

Injuries are inevitable.

That's I would tell myself 3-4 years ago If I could time-travel. As an ex-powerlifting fanatic, I completely understand what it feels like to want to get as strong as possible in the shortest time frame possible, thinking "squat bench deadlift or die".

Elite level strength takes years and years to develop naturally (even when enhanced, actually). If you have good limb and spatial awareness or previous experience with weight training, you might be able to pick up the technique fairly fast. But being able to induce the physiological changes to your nervous system and muscles to tackle 2, 3, 4x of your bodyweight on your back or in your hands, takes time and patience. The earlier you come to terms with that, the better off you'll be when it comes to making decisions about jumping on a high-frequency program when you're not ready, or trying to peak and go heavy too often in your beginner and intermediate stages.

Mental persistence also plays a big role in athletic performance and success. Great athletes are able to face adversity, come back from injury, destroy their egos and doubts in order break through plateaus and have excellent performances. Try to see the positives in each situation, but be self-aware enough to know when you're overreaching when you shouldn't be.

Coming Back From Injury

The best tip I can give you is regarding injury, specifically coming back from an injury.

Many lifters feel the need to play "catch-up" after coming off an injury, doing more than they can handle and putting themselves in a downward spiral. I'm not an advocate of training through injuries, it does not develop mental strength nor improve your likelihood of strength success in the future. The best course of action is to wait for the pain to subside, identify how the injury came to be (accumulation of volume - overuse?, poor technique?, freak accident?), address the weakness, and allow several weeks of training before returning back to pre-injury training volumes and intensities.

This is what I like to call athletic maturity. Being able to keep your eyes on the prize, on the long term goal, and realize every injury is an opportunity to fix a missing link, or improve a weakness.

Just like strength itself, mental strength and persistence can have an innate or "natural" component, but of course can also be developed through repetition and hard work.

Concurrent Training: Science and Practical Application

Concurrent Training is the combination of resistance and endurance training in a periodized program to maximize all aspects of physical performance. This article will review the science behind concurrent training and help you get the most out of your training sessions.

Concurrent Training (CT) is defined as the combination of resistance and endurance training in a periodized program to maximize all aspects of physical performance. Unless an athlete is in a pure-power sport like Olympic Weightlifting, or a pure-endurance sport like long distance cycling; a combination of both power-related and endurance-related attributes are required to excel in mixed-type sports. Mixed type sports are sports that depend on several different energy systems and different strength and speed properties. MMA, boxing, basketball, soccer, hockey and many other team-based sports fall under this category.

In the world of bodybuilding and strength sports, cardio is used as an umbrella term for all types of endurance training protocols. Often as a joke among lifting circles, cardio has been stigmatized to "steal your gains", so far to the point that some lifters see it as a badge of honor to be out of shape and possess almost no cardiovascular conditioning in return for being able to lift a massive amount of weights.

In the world of endurance sports like running and cycling, strength training can be seen as an unnecessary training method that adds unwanted muscle mass to the frame of an endurance athlete, possibly slowing them down and being detrimental to their performance. The term "meathead" might even be applied to people who lift weights.

This article will shed some light on what cardio and strength training has to offer to each training demographic/niche and how a mixed-typed athlete can best organize their training so they reap in the benefits of both training modalities with little to no interference.

The Science and theories behind ct

In one of the first research studies carried out on the effects of concurrent training, Hickson (1980) observed that training both strength and endurance qualities simultaneously had detrimental effects on strength development but did not negatively impact aerobic qualities. Building off of research by Hickson, more recent studies have shown a wide variation of responses in concurrent training, both positive and negative. This suggest that CT methods are still inconslusive and variables such as genetic differences, modality of endurance training, nutritional status and training time may play a role in mediating the effects.

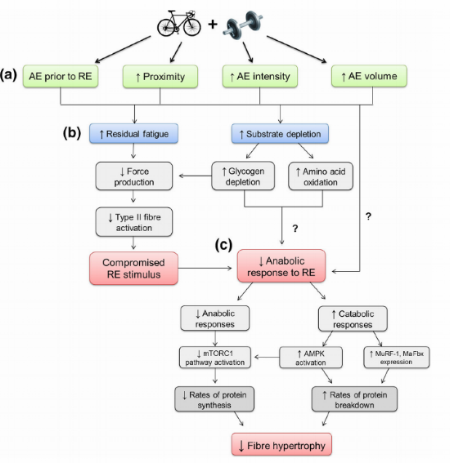

Termed the molecular signaling theory, it has been hypothesized that the distinct molecular signaling pathways of strength and endurance exercise adaptation may be incompatible and inhibit the development of each other.

Other theories speculate that the poor management of both resistance and endurance exercise variables may expose athletes to higher incidents of overreaching and overtraining. For example, the high volume nature of endurance training paired with heavy strength training may make recovery more difficult, increasing the risk of overtraining and injury to an athlete. In conjunction with observing the effects of CT, uncovering the potential mechanisms behind the molecular signaling theory is needed to understand how strength, power and endurance can be developed simultaenously.

Molecular signaling theory

Resistance training adaptations such as muscle fibre hypertrophy, strength and power acquisition are known to be mediated by molecular signaling pathways known as the AKT and mTOR pathways. Resistance exercise that create large force outputs, mechanical tension and stretch, as well as muscle damage and swelling are activators of these hypertrophic pathways (Brad Schoenfeld talks more in depth about this in his frequently cited research article - "The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training"). Many of the compound powerlifts that recruit larger amounts of muscle mass have the capability to create large force outputs and mechanical tension, while exercises such as isolation exercises taken to failure, drop sets, supersets, giant sets, contribute more to metabolic stress and cell swelling.

In contrast, prolonged and repetitive low intensity muscle contractions activate signaling pathways involving the enzymes AMPK and CaMK, which are responsible for adaptations related to endurance training such as mitochondrial biogensis; allowing you to walk, run, swim and bike further and more efficiently.

Capturing the attention of researchers, the observed suppression of mTOR signalling pathways by increased AMPK activation has been the focus and basis behind the molecular signaling interference theory. AMPK activation downregulates and can blunt the hypertrophic response to a resistance training workout or program by inhibiting mTOR and can increase protein degradation through other pathways we won't get too deep into. mTOR can even be downregulated indepedent of AMPK activation, through a family of proteins called SIRT (more information here for the nerds). What you need to know is that when performing cardio training during a resistance program, muscle hypertrophy, strength and power can be compromised.

So were the bros right all along? Does cardio in-fact, kill your gains?

Not so fast. It is not uncommon to see increased endurance performance or improved resistance training outcomes with CT, thus several studies have made arguments for the limitations of the interference theory. In some cases, resistance training can upregulate AMPK, and aerobic exercise can also induce increases in mTOR activity; therefore a positive transfer effect might be present when intensity, volume and frequency of each training modality are strategically manipulated.

It should also be noted that the results of research studying the acute effects of exercise and molecular signaling cannot always be predictive of future chronic adaptations. If athletes have no CT experience, the interference effect might be just occur until the athletes acclimatizes the the CT methods. It is also possible that the interference effect may not be present until later into a training cycle where there is an accumulation of resistance and endurance training fatigue due to increased training loads, or intensity. For example, the original CT study by Hickson (1980) found there were no interference effects until the 8th week of training.

Since molecular signalling has been found to be highly variable depending on the training status of the individual (strength trained vs. endurance trained vs. completely untrained), CT variables must be prescribed based on athletes' current training status and previous training experience.

Concurrent Training Effects on Resistance Training Adaptations

Varying modality, intensity, frequency and volume of training has been shown to affect the magnitude of molecular signaling and protein synthesis. Therefore we know that the degree of interference between signaling pathways can also vary depending on programming variables. Since AMPK downreulgates mTOR signaling and NOT vice versa, its hypothesized CT can be more detrimental to resistance training (RT) related adaptations compared to endurance training (ET) related adaptations.

Muscle Hypertrophy

Muscle size and hypertrophy is a highly sought after adaptation in the fitness world, both as a means to improve metabolic health, and a way to achieve an aesthetic physique.

With several studies concluding that CT blunts muscle hypertrophy, excessive training volume has been predicted to be the cause of overtraining and fatigue when comparing CT groups to resistance training only groups. Based on our knowledge of exercise adaptations, we should know that RT volumes performed by an elite bodybuilder cannot be concurrently trained successfully with ET volumes performed by an elite triathlete due to nutritional and time constraints. However, to date, there is no conclusive evidence that hypertrophy is blunted when low-volume aerobic exercises is added into a training program; some studies have even shown it might mitigate muscle loss (Study #1, Study #2). High volume ET on the contrary, can be detrimental due to the factors discussed above (interference theory OR overtraining/fatigue theory OR... both). For practical recommendations on how to avoid interfering with your hypertrophic workouts, read below in the practical application section.

Strength & power

In a large scale meta-analyses of CT effect sizes, Wilson et al (2012) observed that in many studies, power was significantly lowered during CT while muscle cross sectional area and strength was maintained. This suggests that force at high velocities (think of a vertical jump, NOT a heavy squat) may be affected to a more significant degree with concurrent ET than force at lower velocities. The mechanism behind this could be attributed to motor unit and specific muscle fiber type innervation. During classical long duration endurance exercises, the majority of muscle action and force production comes from low threshold, fatigue-resistant type I muscle fibers. There may be a shift from type IIx fibers to type IIa fibers or type IIa to type I fibers to accommodate the oxygen-demanding adaptations of endurance exercise during concurrent training therefore aerobic exercise can be detrimental to athletes that require a high rate of force development rate and power when poorly programmed into a periodized plan.

To better compliment the demands of strength and power sports, prescribing lower volume - higher intensity and velocity interval type ET may be more beneficial in terms of maintenance and improvement of power. This may be because of the similarities in the motor unit/muscle fibre recruitment patterns in RT and high-intensity based ET. When viewing this from an interference theory stand point, the high energy costs and high activation of AMPK from high-intensity ET could potentially magnify the interference effect but the research does not support this claim as there has been no cases of muscle mass loss when high-intensity ET is prescribed in a low-volume fashion. Research isn't conclusive but it is clear the intensity and volume of endurance training affect muscular strength and power outcomes.

When it comes to training modality, it is hypothesized that modalities that require a lot of eccentric muscle action can cause excessive muscle damage, further impeding the muscle recovery process from a challenging RT session. Because of this, predominantly concentric movements, are favored over running (a movement that includes a lot of eccentric contractions - think of every time your foot strikes the ground), like cycling and prowler pushes. Cycling, specifically hill climbing, can also resemble resistance-like loading patterns and can induce lower body hypertrophy that may compliment RT adaptations. Following this stream of thought, other ET modalities that possess lower eccentric muscle action and lower impact stress like swimming or modalities that have similar loading patterns to resistance training such as prowler-pushes and sled drags can also be used to improve cardiovascular conditioning when training concurrently.

Concurrent Training Effects on Endurance Adaptations

Well-trained athletes often show different responses to exercise compared to untrained individuals, endurance athletes are no different as they may see dissimilar improvements from RT compared to untrained or already resistance-trained individuals. High volume and high frequency endurance training make it hard for endurance athletes to improve muscle size, strength and power without cutting into the recovery process of ET. Paired with the high energy expenditure and AMPK levels from ET, CT can be problematic for endurance based athletes.

Wang et al (2012) showed that resistance training following endurance training elicited greater PGC-1a actavation (a regulator of energy metabolism and endurance adaptations) and therefore more oxidation capacity improvements than endurance training alone. The increase in activation of PCG-1a was thought to be related to the high amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and lactate concentrations produced during CT vs. endurance training alone. AMPK activation however, was not a plausible explanation for the improvements in oxidative capacity as AMPK was similar in both the CT and ET-only group. The researchers suggest that the RT portion of the CT group upregulated mTOR, which had a positive effect on PGC-1a. The interactions between mTOR and PGC-1a also have implications for muscle and endurance performance.

Another study concluded that resistance training has positive implications for endurance performance, mainly due to increases in type IIa muscle fibers and a greater potential for force production (Study). This means endurance athletes that concurrently resistance train can improve their average and peak power outputs, which play a big factor during races and time trials. In addition, a study looking at the effects of CT found that pairing strength circuit training along with an ET program (same workout session) improved aerobic performance more than an ET program alone where VO2max and 4km time trial performance both increased slightly more in the CT group compared to the ET only group. The beneficial effects of RT for endurance athletes cannot be overlooked!

Resistance training can also benefit endurance events of different durations. For shorter, more anaerobic dominant endurance events like the 400m/800m run, most swimming events and many team sports, performance can be improved by increasing muscular strength and neuromuscular function that can't be achieved with ET alone. For long aerobic endurance events and competitions like marathon runners, and triathletes, improvements in performance can be attributed to the higher economy of movement induced by RT (study), which simply means endurance athletes that resistance trained were able to more efficiently use their energy to travel at any given velocity, saving them energy in a long race.

Concurrent Training Timing

(AE = Aerobic Exercise)

(RE = Resistance Exercise)

Disclaimer: This is not my chart.

If we base our training order off the molecular signaling theory of the interference effect, ET would be best performed prior to RT (within the same day). Since AMPK downregulates mTOR and not vice versa, an ET session that raises AMPK levels will not have a chance to interrupt mTOR signalling if RT is performed after. But we also need to take into account other facts to help us maximize training adaptations and minimize any interference.

The interference theory can manifest in the form of negative interactions between protein activity and molecular signalling, but coaches cannot overlook the more simple explanations as to why there might be an interference effect when training several physical attributes or modalities. Reduced training quality can also be an explanation as to why CT causes interference problems. For example, after performing a ET session, performance in the subsequent RT session may be diminished due to pre-exhaustion. This is problematic if a particular athlete needs to prioritize his/her RT session because of their personal goals, weaknesses or position on a sports team. Coaches and athletes must plan and prioritize which training sessions are more important and the introduction of rest and nutrition must be taken into account to mitigate any interference effects.

In order to minimize the fatigue and the interference effect, a 24-hour recovery period between training sessions is suggested; the longer the better. However, this suggestion is often not practical for subelite or elite athletes that want to or are required to train 2 and up to 3 times a day. Based on the time course of AMPK elevation and it's downregulation of mTOR signaling, a minimum recovery time of 3 hours is suggested between ET and RT sessions. Although 3 hours is enough to reduce the molecular signaling part of the interference theory, its also suggested that 6 hours or more is needed to reduce the muscular fatigue from the previous ET bout and retain muscular performance during a subsequent RT session. When high-intensity ET was performed prior to RT, force production was reduced for at least 6 hours, while the capacity to perform higher volume RT was also diminished for up to 8 hours. As noted by Robinuea et al (2014), technical and tactical training sessions in team sports also have an cardiovascular and endurance component to it, not scheduling adequate rest before a subsequent RT session could be detrimental to performance.

Nutritional Protocols For Concurrent Training