Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

This programming article series will be split into 2 parts.

In part 1 (this article), we will start with a low resolution view of training, in other words, the bigger picture. We will cover big concepts that guide our decisions when it comes to long-term athletic development and month to month training.

In part 2, we will work our way down to the specifics like week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

READ PART 2 ON MICROCYCLE AND WITHIN-SESSION PLANNING PROGRAMMING HERE

the MAcrocyclic layer

In training periodization, the macrocycle is the largest division of training periods, usually several months in length or even a years. When planning on the macrocyclic layer in combat sports, we are concerned with the long-term development of athletes. What the overall career trajectory looks like (considering factors like training and competition age) as well as overall athletic development/progression from fight to fight.

Below are some philosophies and frameworks I use to govern development on the macrocyclic level.

LTAD Model

The long-term athletic development model (LTAD) model is a framework created by Dr. Istvan Balyi to guide the participation, training and competitive aspects of sports and physical activity throughout different stages of development for any athlete.

No matter what stage an athlete comes into the sport, a base must be built for performance potential to flourish in the future. Whether your athletes’ goal is to compete in boxing, wrestling or Judo in the Olympics, or turn to a career in prize fighting for international organizations such as the UFC or One Championship, a coach must see S&C as a long-term investment. Coaches that partake in short-term thinking - disregarding joint health, brain health and overall athletic longevity do nothing but limit the potential of an athlete.

Skill Practice Rules All

The skill practice rules all paradigm acknowledges that skill is the most important aspect of combat sports, rather than physical ability. S&C coaches new to the combat sports world are hesitant on adopting this philosophy (the ones who do fail to manifest this in their programming) as many of them view high performance training through a purely physical and bioenergetic point of view - thinking that maximum strength, power and great endurance (as objectified through lab testing numbers) is what ultimately influences the outcome of a fight.

However, by undervaluing sport-specific skills such as pattern recognition, tactical strategies and fight experience, these coaches make mistakes in the training process that sacrifices skill development and expression for superficial strength and power gains.

Without getting into too much detail, I’ve used this skill practice rules all paradigm to influence my programming so that training stress is distributed more optimally throughout training camps and S&C plays a supplementary role, allowing skill expression to shine on the night of a fight.

If you’d like to learn exactly how I apply this into my S&C programs, I highly recommend you check out the eBook I mentioned earlier.

The Barbell Strategy

Originally a financial investment strategy, the barbell strategy adapted to S&C involves utilizing “low-risk” training methodologies as the main driver behind performance improvements; only prescribing special developmental exercises and “high-risk” exercises when the foundational bases have been thoroughly covered.

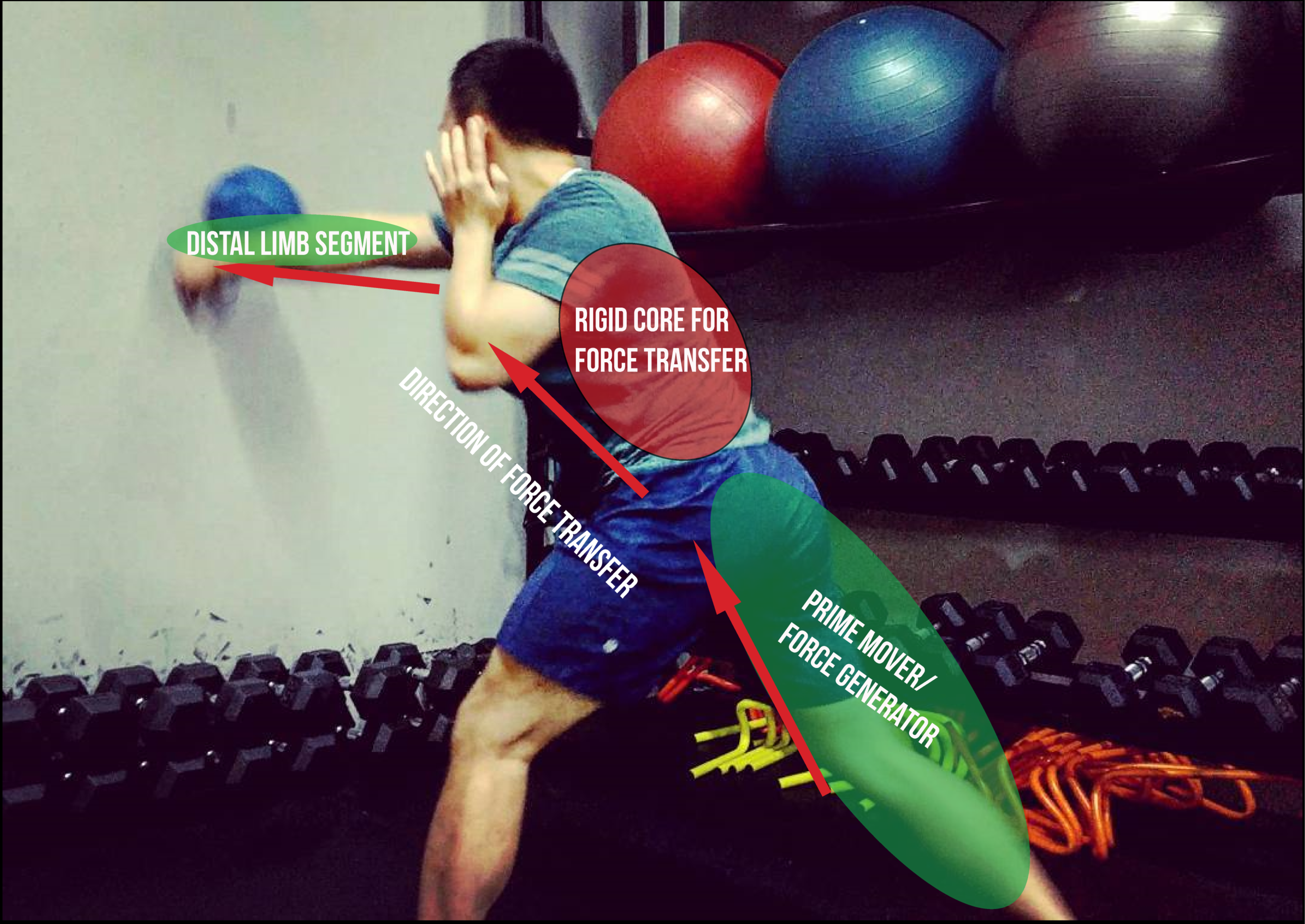

With the rise of social media and wild exercise variations promising transfer to the sport, it’s easy to get lost and major in the minors. Landmine punches and brutal conditioning circuits have a place in combat sports S&C but plays a very small role in driving meaningful improvements in fighters.

As a rule of thumb, 80-90% of time should be invested in “low-risk” exercises, and the rest 10-20% into more specialized training. However, don’t fall into the trap of thinking “low-risk” exercises are don’t drive any improvements in sports performance or that they are picked blindly, they should still be selected with the physical demands of the specific sport in mind. A comprehensive needs-analysis of the sport needs to be performed beforehand. Given the limited time I may have with a fighter (2-3 sessions a week), I must select exercises that have a favourable cost-to-benefit ratio.

Looking at the bigger picture, the barbell strategy keeps my programming and exercise selection process grounded by reminding me what improvements I can realistically make with combat fights as an S&C coach and what influence I have over the training process.

Agile Periodization

This is a term coined by S&C coach Mladen Jovanovic. As described by Mladen:

“Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistic approach to planning” (Jovanovic, 2018).

Agile periodization represents a training philosophy that’s based on the uncertainty of human performance and one that permeates multiple layers of my programming and planning.

Rigid periodization models that we S&C coaches learn from textbooks and university classes unfortunately have little success given the unpredictability of the real-world and the volatility of combat sports training schedules, competition dates and career trajectories. Furthermore, mindlessly following scientific dogma and abstractions give us a false sense of predictability and stability in the training/planning process.

While we still need to set objective long-term goals and have a vision of what success looks like for our high-performance athletes, the agile periodization framework encourages simultaneous bottoms-up planning: what does the next best step look like given the athletic and environmental constraints in front of us? Does the long term goal change with the new information we’re receiving about the athlete and their progress?

The mesocyclic layer

Mesocyclic planning is concerned with how training variables change from month to month - most of these strategies have fancy names and are ones you normally hear when reading about training periodization.

The overarching goal with mesocyclic planning is to create a training program that bests develops the athletic qualities a combat athlete needs in order to excel at their sport. Whether these qualities should be trained simultaneously, sequentially or in a specific order is what makes one periodization model different than the other.

Let’s explore a few options.

Block Periodization

Commonly confused with programs that simply have “blocks” or “phases” of training, block periodization (BP) is a specific periodization strategy popularized by soviet coaching figures like Verkoshanksy, Bondarchuk and Issurin (article here on a review on different types of training periodization). BP consists of distinct blocks of training aggressively targeting certain physical qualities, such as maximum strength, or plyometric ability (and doing the bare minimum to attempt to maintain other qualities). The basis behind BP is that elite-level athletes who are reaching the functional limits of their physical performance require highly concentrated training loads in order to further increase performance. This becomes problematic when translating it to the world of combat sports training. Here’s why:

Imagine a 4-week block dedicated to increasing maximum strength where the majority of your weight room training volume comes from heavy lifts above >85% of 1RM. The lack of a high-velocity stimulus combined with the fatigue incurred throughout this block will unquestionably hinder an athlete’s ability to develop new skills on the mats or clock in high-quality sparring sessions.

The physical demands of combat sports are not extreme (compared to pure-strength or pure-endurance sports), what’s important is improving key qualities slowly over time while still maintaining physical and mental energy to excel in the practice room - where it counts.

It’s a good idea to separate training into distinct blocks/phases with clear goals, However, implementation of BP, characterized by aggressive investments into single traits and heavily reliance on cumulative and residual training effects, is best left for sports like cycling and powerlifting.

Triphasic Training

Triphasic training, popularized by Cal Dietz, also shares some elements of block periodization, where each block heavily emphasizes the eccentric, isometric and concentric (3 phases - triphasic) muscle actions sequentially to improve speed and power at the end of the block.

Typically, a general preparation phase (GPP) is done prior to jumping into a 6-week triphasic training phase consisting of 2 weeks of eccentric focus, 2 weeks of isometric focus and 2 weeks of concentric focus. This is all capped off with a high velocity peaking/realization block lasting several weeks (depends on the athlete/sport/schedule).

Much like block periodization, triphasic training requires adequate preparation time before a fight or competition and can run into the same problems that BP does, of sacrificing quality of skills training in order to further build physical abilities.

Some coaches have made this work, notably William Wayland of Powering Through Performance, who adapted the triphasic model to MMA athletes, compressing the model and by utilizing supramaximal loading. William breaks it down much better than me so I suggest reading up on it here: “Applying The Compressed Triphasic Model with MMA Fighters”.

Concurrent Method

Like the name suggests, this method involves developing multiple physical qualities concurrently, from month to month. The emphasis on each quality is not implemented as aggressively as it would be in BP or a triphasic set up, so it allows for more programming flexibility - changing intensities and volumes where the S&C coach sees fit (see agile periodization).

By training concurrently, the training stimulus is spread amongst all physical qualities (endurance, strength, plyometric ability, power-endurance, etc) - no physical trait is being neglected, therefore an athlete’s physical readiness remains relatively stable from month to month. A potential downside to this method is that if we’re spreading the training volume thin amongst different traits, we risk watering down the training process and end up not making any tangible process in each area.

Contrastingly, this coincides with the concept of minimal-viable program (MVP) brought up by Mladen Jovanovic, a concept that states that a program that covers all areas will, over time, tell us what changes need to be made based on strengths, weaknesses and any data that comes out of that. Each subsequent training phase will then be modified to suit the needs of the athlete.

These paradigms and philosophies that occur on the macro- and mesocyclic level govern the way we view physical preparation for combat sport athletes, also affecting the decisions we make downstream. In part 2, we will go over strategies we can apply on the microcyclic level and within any given S&C session. (Click here to read part 2).

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)