Optimizing The Warm-Up Using RAMP & Mobility Flows

The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

Its the general consensus that a warm-up is a mandatory component of any training session, no matter what sport or athlete you’re working with. The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

As a result of poor practices in the past, as well as noticing trends in the high-performance world, I remain unconvinced on the concept of needing to perform an overabundance of exercises to “activate” muscles or “mobilize” the joints prior to training. Banded distractions, foam rolling, all the bullshit that people waste their time on because “that’s how everyone else does it in the industry”.

I was unsatisfied and baffled over the fact that a warm-up could potentially take up 25% of the time out of a training session. The warm-up is the low hanging fruit in terms of programming improvements. Simple changes to the warm-up protocol afford coaches and athletes more time to put into more meaningful training that develops athletic performance.

Out of a necessity to make my personal coaching sessions run in a more smooth and efficient manner, I’ve created a mobility flow warm-up as a way to address the first 3 letters of RAMP within one series of exercises.

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

(R)aise body temperature

(A)ctivate muscles

(M)obilize joints

(P)otentiate to reach intensities seen in the training program

In this mobility flow, I’ve sequenced multiple foundational movement patterns together such as squatting, hinging, lunges, pressing and rotating. Alongside the obvious rise in body temperature from performing this, the emphasis on large range of motion movements and anti-rotational positions addresses both the “activation” and “mobilization” aspects of a warm-up, saving time that can be put into actual, meaningful training.

While this mobility is ground-based and has a lot more potential for additional exercises, the principles I work with remain the same - achieve rise in body temperature, put muscles and joints through a large range of motion and improve proprioception as quick as possible. Modify this flow as you see it fits your training demands.

After the mobility flow, some sort of potentiating training follows in order to reach the intensities seen in the training session (whether the session is strength-based, plyometric-based or concurrent). More details about exercise order and potentiation can be found in my exercise order article.

Application

This mobility flow can be performed as a warm-up, as a cooldown, or as an active recovery protocol.

Warm Up: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Cooldown: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Active Recovery Protocol: Multiple sets of 3-5 minutes, or one long set of 15-30 minutes (Keeping HR in Training Zones 1 and 2)

Great response from my athletes so far. Will be refining this over the next few months. I hope you enjoy it.

My Thoughts on the FMS (Functional Movement Screen)

I recently had someone ask me whether getting the FMS certification was worth it. Like many questions, I answered... "it depends".

FMS Certification For Trainers & Coaches: Good Idea? Or Stay Away?

I recently had someone ask me whether getting the FMS certification was worth it. Like many questions, I answered... "it depends".

For those who don't know, the FMS (functional movement screen) is a fitness assessment created to look for "movement dysfunction". The FMS can be a good tool for new personal trainer and coaches to use as an initial assessment and as practice as they become more familiar with human movement. But becoming dependent on an arbitrary set of exercises to understand movement dysfunction and predict injury risk is something many trainers and coaches should avoid as they progress through their career.

Using pre-determined movements and quantifying movement quality is the complete opposite of conscious coaching and dismisses the idea of movement variability.

Conscious coaching requires adaptability and interaction.

Stop staring at your piece of paper; start watching your athletes and patients move. Figure out which movements are required in their sport or daily life because the definition of "functional" movement varies from sport to sport and one environment to the next. Talk to your athlete or patient about their confidence (or uncertainty) about particular body positions or movements. Design well-structured training programs that control for load, fatigue management, and injury reduction. Since your athletes and patients will most likely come from many different backgrounds, conscious coaching and assessment will do heaps more than some standardized test will.

This is not to say I'm against writing anything down. Notes should be taken when necessary.

Instead of writing: "Scored a 2 on the lunge test", a conscious coach will watch their athlete and note: "knee valgus during fast change of direction when running - check hip and leg complex and assess previous injury history and running/agility technique."

Some argue that the fact that FMS can be standardized to help sports teams. Several of studies have come out showing that their findings do not support the "predictive validity of the FMS" and that the FMS does "not relate to any aspect of athletic performance", so using an invalid assessment is stubborn and a waste of precious time, no matter how consistent it is. Can the FMS be useful? Of course. But consider the picture blow:

The FMS is 8% better than a coin toss. Let that sink in.

Like I said earlier, the FMS can be useful for new trainers and coaches. However, the end goal should be to acquire enough knowledge on human movement, motor learning, movement variability and training load to be able to consciously watch our athletes and clients. The FMS is not a game-changer and I would advise you to consider whether or not getting certified will help you towards your goals given your current experience level.

Be adaptable.

The Current State Of The Fitness And Training Industry

This article is a reflection of the current state of the fitness industry and my opinion on the most commonly debated topics.

Over the past few years, social media and online interactions have been one of the main drivers in the fitness, personal training and coaching industry. The general population now have access to the most knowledgeable coaches, the best training advice and the most informative articles with just a click of a button. Trainers and coaches from all around the world also get to discuss the latest training and dieting protocols and sell their services to others.

However, with any good thing, come the negatives. Call-out culture, trolling, underqualified trainers and coaches, lies and accusations about other trainers, over-saturation of information, I'm sure we've seen it some of these to an extent. With that said, is this new age of fitness and personal training really a good thing.

This article is a reflection of the current state of the fitness industry and my opinion on the most commonly debated topics.

I've only been in the game for 5 years, but I'm lucky to be connected with the most brilliant minds in the fitness, nutrition and strength & conditioning realm. Our industry is special in that training methods, diets, and expert opinions can all be criticized and scrutinized on an open platform, Facebook, without much anonymity. Despite the stereotype that Facebook can't be used for serious and civil conversations about any complex topic, it's surprising that trainers and coaches around the world can participate in scientific discourse about all things related to human fitness. Anything you say or post will be read by your peers and can be criticized and improved on; so long that you're connected to the right people and not committing cases of confirmation bias on the daily basis (avoiding criticism or change, always seeking out people and information who agree with you).

I also remember when this was not the case. I remember when Facebook was just a platform to share your fitness routines and update your friends on your latest physique or strength progress. Over the years Facebook has become a vehicle for distributing truthful, evidence-backed fitness and nutrition advice. At the same time, a tool for trainers and coaches to market and sell their services and information. I don't understand fully how this came to be, but I have a few theories:

Fitness is a personal pursuit, but has a big social impact.

Improving health, fitness and looking great naked is a personal pursuit. YOU have to put in the time in and YOU have to put in the hard work to benefit YOURSELF. However, humans are social creatures. Some post pictures of themselves to motivate others, some workout to show off their bodies, some want validation and approval from others. Whatever the intentions are, sharing your fitness journey on Facebook has a huge impact on your circle of friends on Facebook. This is akin to foodies posting pictures of great local meals or car enthusiasts showing off their newest car mod; there's something positive and gratifying about being able to share your own experiences with others.

Social media is the perfect platform for marketing personal training services and, but can be very dangerous.

Social media can also be a platform for marketing personal training services and diet plans. Often paired with paragraphs about why and how your methods are scientifically proven to be effective or the best. I do this, many other trainers and coaches I know do this. It's an effective way to reach an audience you've already built through friendships in high schools or a way to acquire clientele through the acquaintances you've crossed paths with from work or weekend-hobbies.

Marketing on social media can also be very dangerous. It's easy to subscribe to too many different trainers with different view points, or at worse, subscribe to someone who teaches ineffective training methods and gives out dangerous nutrition advice. This results in an over-saturation of information for the general trainee and trainer, leading to something many people call "paralysis by analysis": over-thinking fitness and nutrition to the point where the trainee or trainer fails to stick with the basics or is confused to what steps to take to reach a goal.

Peer-reviewed scientific papers do not have the same reach and impact as a evidence-based coach that can effectively communicate to the masses.

Scientific journals and papers are made for scientists and researchers to communicate with each other, using statistics and logic to come to a consensus about a particular topic. The use of complex scientific terms is crucial for maintaining consistency in the field, but might not be the best for communicating with the masses on Facebook. Using scientific jargon and anatomical terms may be valid, but the average trainee or local personal trainer that don't possess the same vocabulary will be lost in the forest.

Share a breakthrough scientific article on carbohydrates and weight loss. You might get 100 views.

Read a breakthrough scientific article on carbohydrates and weight loss, dissecting the main points and communicating those points using both scientific and lay-man terms so the masses can understand and put to practice? Watch your view count go through the roof and your social impact increase.

This is what is so great about podcasts like Danny Lennon's Sigma Nutrition Podcast and research reviews like Alan Aragon's Research Review. They speak with respected researchers in the field and are able to package information in a way most people can understand.

This is not to say peer-reviewed scientific papers and research studies are not useful, far from it. Rather, we should be mindful of the way we communicate with our audience. Using the right terminology or using communication techniques like analogies can help, and are very important.

Call-Out Culture

Also related to Facebook and social media, I wanted to talk about "call-out culture" in the context of the fitness and nutrition world. This topic came to my mind after a thoughtful coach raised a question on Facebook on what the term "evidence-based" really means in the fitness industry and where to draw the line to divide people who are truly evidence-based away from those people who aren't.

Some trainers, researchers and coaches pride themselves for calling out bullshit they see in the industry, whether it be training methods that aren't scientifically backed or nutrition protocols that are considered fad diets. Some go as far as publicly shaming them on a Facebook status or write a whole article about why someone is wrong.

While I believe trainers who give out shady and dangerous advice should be called out, we have to examine their intentions:

A trainer who is purposely promoting stupid training methods and useless supplements for financial and egotistical gain at the expense of their follower's health and money, is an asshole and should be called out.

A trainer who has good-intentions but has mistakenly spread false information either from a lack of education or lack of carefulness, should not be bashed.

Much of the false information and pseudoscience I see being spread is by the latter group of trainers (I could be wrong...)

The best way to go about this problem is not to fight negativity with negativity, rather smothering them with positivity and giving them a chance to improve their critical thinking skills by providing them with sources (articles, podcasts, videos) that publish good information. Approach the coach or trainer in a respectful manner and challenge their ideas by making sound, logically points as to why they've made a mistake or that their information is outdated. If they fail to acknowledge the new information, your options are to 1) leave them alone, 2) reconsider your own stance and how to approach these types of trainers in the future. Forcing your ideas, or belittling them in a threatening manner benefits no one.

Positivity is something I've picked up from being a business owner. Trainees and potential clients are much more likely to be drawn to you if you're passionate about making a positive change. Constantly shitting on other trainers and failing to provide any useful advice to your own audience is a recipe for failure, something I've learned personally. Spending more time on honing communication skills and having good intentions is the key to making a positive impact you want to see in your clients, athletes and audience.

I understand that a budding scientist that dedicates their life to a particular area of research would be more likely to take offence to a personal trainer online spewing out false information about his/her area of expertise. The said scientist would then be more inclined to participate in call-out culture.

Call-out culture is bad for business and social impact, but may be practical for keeping misinformation and psuedoscience out of scientific discourse. It's all about context.

Stay in your own lane

"Stay in your own lane". The most dangerous, yet best advice any personal trainer and coach can receive.

Dangerous in the sense that this piece of advice can convince a trainer or coach to not branch out of what is currently comfortable to them; suppressing creativity and continuing education.

Best in the sense that trainers should not attempt to use practices and methods they are not fully comfortable with just to make a quick buck or play a know-it-all guru.

I do believe trainers and coaches should go out of their way to learn about topics they're not comfortable or educated on. Well-roundness and adaptability is what every professional should strive for. Learning about areas outside your scope of practice can provide perspective and benefits that "staying in your own lane" cannot achieve. I became a much better strength coach after dabbling in the world of pure endurance training, which lead me to researching about concurrent training theories and methodologies; ultimately improving my program writing abilities. This is just my personal example. I've seen some physiotherapists branch out into the strength training world, integrating strength training principles into their rehabilitation system to better understand and change the lives of their clients. Some have even completely overhauled how they look at the world of physiotherapist after understanding strength training, the adaptability of the human body, and how everything is interconnected.

A more common example would be trainers studying for a nutrition diploma or certificate to better understand how to adjust their clients' diet and dietary habits in order to fully reap in the benefits of fitness training.

So what's wrong with branching out? Why shouldn't trainers and coaches stay in their own lane?

The biggest problem is the self-inflated confidence of trainers and coaches that believe they are experts in areas they have barely scratched the surface of. Obviously this is a grey area. There is no line to draw to know when you're informed enough to give out advice on a particular topic. This part involves a lot of self-reflection and objectivity, so it's no wonder trainers get it "wrong".

There's a spectrum of people who don't stay in their own lane. Trainers who play sport nutritionist only having learned about "if it fits your macros" a few months ago. Personal trainers who play manual or physio-therapist despite not receiving any formal education in the area. Trainers who receive a NKT or cupping certificate over the weekend and think they're rehab gods or have figured out the code to rehabbing injured patients (don't even get me started on this). I could go on and on...

To make a quick buck, or to make themselves look like more of an expert. It doesn't matter. It waters down the field and is completely disrespectful to the professionals that have been in the trenches and have put in years learning the particular area or topic. It's not only stubborn to think that one can learn the in and outs of an area over the weekend, but dangerous to the potential clients, athletes and patients that follow these trainers.

Do some self-reflection on how much you really know of a topic before you decide to sell your services. Learn how to say "I don't know, I'll refer you to someone or I'll try to find out for you" to your clients and athletes. Be curious and sell the best services you can to your clients, but be humble.

The Fitness Industry Moving Forwards

With the rising popularity of celebrity diets, Instagram model-sponsored supplements, squats on bosu balls and all the problems I've been discussing above, is the state of the fitness and personal training industry the worst it's ever been?

I don't believe so. I think it's actually the best it's ever been and is improving a greater rate than ever before.

Availability heuristic is a cognitive bias that causes you to make incorrect assessments and assumptions, making you believe something happens more frequently or is more prevalent than it actually is.

If you ask the majority of people, they'll think poverty, murder and terrorism is much more serious and more prevalent than it was a few years or decades ago. When in fact, poverty and mortality rates have been as low as they've ever been, and other areas like literacy and basic education have been steadily improving (look at the figure below).

The increased exposure to social media, news outlets and daily news has made us believe these problems are more rampant than they actually are. People believe ISIS is the worse group ever in the history of the world, when there have actually been multiple factions of terrorist groups that have carried out the most gruesome massacres and genocides before the popularity of social media and news.

On a less serious note, some people in the fitness and personal training industry suffer from this availability heuristic. You see advice about knees not being allowed to go past your toes while squatting? You might be convinced the majority of trainers still don't know how to teach a proper squat.

Yes, there are still trainers spewing out garbage, big supplement companies are still cashing in money on people gullible enough to buy a plethora of useless supplements. But don't forget about the increased financial awareness of consumers in the age of technology, the ability to read reviews on fitness products, as well as the thoughtful debates and discussions about fitness and nutrition on Facebook (I use the word "thoughtful" loosely haha).

Anecdotally, I also noticed the personal trainers down at the local commercial gym have been improving as the demand for higher quality training from more self-aware consumers has been increasing. It's much harder to get away with heavy squats on a bosu ball nowadays without getting your fitness page and reputation ripped to shreds.

Here's a list of why I think the fitness industry is the best it's ever been:

The growing skepticism and awareness of consumers drives companies to create higher quality products

Amalgamation of professionals from different niches (Personal trainers, dieticians, strength & conditioning coaches, sport psychologists, rehabilitation therapists) on Facebook and online forums

The rise of evidence-based training and nutrition plus the growing demand for these methods

The benefits of strength training are reaching and influencing a greater number of people

More women are buying into the benefits of strength training and competing in strength sports

The pure strength training circle is starting to see the performance and health benefits of including cardio and endurance training

The biopsychosocial model of pain and rise of pain science is changing the way rehabilitation professionals look at injuries and chronic pain management

Trainers and coaches are able to help a wider range of clients worldwide through online training

Evidence-based nutrition recommendations plus knowledge of flexible dieting and intuitive eating are helping people reach their body weight and body transformation goals more effectively; alleviating body image issues and eating disorders

There will always be myths to bust and fad diets to tell people to stay away from, but I believe the fitness industry is improving. Maybe I'm suffering from avaiability heuristic myself, but as a trainer that used to be very vocal and cynical about bro-science and poor advice, I can't help but accept the fact that this industry has improved significantly since I started and can't wait to see what the future holds.

Have an opinion? What are your thoughts? I'd love to hear them. Comment down below or visit me on my Facebook page!

How To Get Started With Your Fitness and Diet Routine: Discipline, Motivation and Delaying Gratification

Picking up a new skill or committing to a new lifestyle change can be difficult, even down right daunting for some. As someone who constantly tries to challenge himself and help others overcome their biggest barriers, I see a big common obstacle holding people back.

Picking up a new skill or committing to a new lifestyle change can be difficult, even down right daunting for some. As someone who constantly tries to challenge himself and help others overcome their biggest barriers, I see a big common obstacle holding people back.

Many people are afraid to pursue new hobbies and learn skills because they're afraid their time commitment won't be worth it. In the realm of fitness and dieting, people hesitate to start to a training program if they don't see the value in it or if they don't believe the results will be worth the hard work. Let's face it, starting a work out plan SUCKS. You are get sore, you get tired, you feel like puking and worst of all, you don't see results until a few weeks in. Humans are naturally unable to hold of short-term gratification (continue living a sedentary life style because its easy) for long-term success (better metabolic health, fitter, healthier) - it's a survival mechanism! Why start a training program or diet if it cuts into your current schedule and takes time away from the hobbies you love? What if results aren't guaranteed?

The Marshmallow Experiment was a series of studies led by a professor from Standford University. In these studies, children were offered an immediate rewards (marshmallows or cookies in this case) or a much larger rewards (several marshmallows) if they waited for a short period of time. Follow-up studies found that children who were able to wait had better life outcomes.

Similar studies were done with younger adults who were offered either $5 immediately, or $15 if they waited a day or two (can't seem to find the studies, feel free to PM or link it to me if you do find it!).

My point is, the biggest obstacle that people face with their fitness goals is the uncertainty about the future. Being able to fight through pain and becoming more comfortable in uncomfortable situations, like from your first few weeks of working out and dieting, is crucial for long term success and health. I understand it's hard, but here are some solutions:

Educate yourself:

Watch a 10 minute video on fitness everyday. Expose yourself to the lifestyle before jumping in head first. This will help you build confidence.

Learn about the benefits of resistance training and cardiovascular exercise

Most importantly, find examples of people you know who have changed their life for the better through healthy living, exercise and fitness. Talk to these people. Ask questions! They'll be glad to share their story and help you.

The education process reinforces the notion that results WILL be made if you put the work in. You just have to give it time. This relieves uncertainty about the future and gives you direction and affirmation.

Ease your way into a routine:

Start off with 1-2 workouts a week.

Make small changes to your diet, whether its by elimination (no more soda or sugary drinks on weekdays), or introduction (including a minimum of 2 green salads on the weekend).

This is the "testing the waters" part. Gradual changes to your current lifestyle is the easiest way to transition into a more healthier one.

Big overhauls to your diet or schedule can be very effective, but be careful of burnout or rebounding. If you're a person that receives motivation through faster initial results, a big overhaul or sudden lifestyle change might be beneficial. This is why "fat loss challenges" or "30 day transformation challenges" can be so successful.

I hope this helps you kick start your fitness journey!

For a more detailed article on how to more successfully build habits in the fitness world, read my article "The Ultimate Guide To Building Sustainable Fitness Habits".

Lose Weight By Eating More?

Anyone who's followed a diet will notice that consuming less food can often result in lower energy levels throughout the day, negatively affecting our mood and most importantly, our activity levels. The better alternative is to eat a bit more to sustain a more active lifestyle. Learn more in this article!

Before anyone jumps down my throat, yes, I know well that to lose weight you have to be in a calorie deficit - eating less calories than you burn.

However, anyone who's followed a diet will notice that consuming less food can often result in lower energy levels throughout the day, negatively affecting our mood and most importantly, our activity levels.

NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis)

Represents all the physical activity throughout the day that isn't considered exercise - walking, fidgeting around, work, etc. When you restrict calorie intake, it can cause you to move less outside of the gym in your daily life. This decrease in NEAT can ultimately cause your fat loss to plateau. Although this is doesn't happen 100% of the time, it's smart to and monitor your physical activity using a basic activity tracker like the FitBit for example and see if your activity levels drop when dieting. It's also smart to be more aware of your mood from day to day and how it affects your motivation levels and your ability to get up and move.

I've written in detail about NEAT and daily calorie expenditure, what they are, and how to use it to your advantage to help your weight loss and fitness goals. Click here to read.

I am in no way advocating for ridiculously high calorie intakes and trying to catch up on your weight loss by performing hours upon hours of exercise. Most people do not have the time nor energy to do so. What I'm advocating for matching the positive mood and motivation levels that comes with a more moderate calorie intake, with higher NEAT levels throughout the day.

If you feel groggy and unmotivated eating 2000 calories a day, it may be smart to increase it to 2250 or a number you'll feel more comfortable or happier at. From here reach a calorie deficit by an extra 5000 steps a day or by staying more active outside of the gym.

Go for a walk on the beach. Go for a bike ride. Move more around the house. Keep yourself active, but keep it simple. The main goal here to is develop a more active lifestyle and making small tweaks to our diet to better accomodate it. Hope it helps!

Why The Pyramid Works So Well In Fitness

The pyramid works well in the fitness industry because it takes into account priorities, and base building. In an industry where the flashiest and most "advanced" training and dieting programs are being pushed down the throat of the consumers, educating beginner trainees on the importance of simplicity is crucial.

We've all seen training and nutrition principles put into a form of a pyramid before (some examples below), but why a pyramid? Why not a pie chart or a flow chart? Let's discuss.

The pyramid works well in the fitness industry because it takes into account priorities, and base building. In an industry where the flashiest and most "advanced" training and dieting programs are being pushed down the throat of the consumers, educating beginner trainees on the importance of simplicity is crucial.

Priorities

Everything you do in your training and nutrition should be effective and time efficient. Using a pyramid really illustrates what aspects of your training and diet needs the most focus on, and which aspects will give you the most bang for you buck.

Let's take the nutrition & fat loss pyramid for example: 90% of your bodyweight goals will come from just paying attention to calorie intake. Eating less calories than you burn will result in weight loss. However if you're concerned with keeping the most muscle mass as you can for aesthetic, or performance reasons, this is where we move up the pyramid and take into account macro-nutrient distribution (in this case, adequate protein intake), making sure you're hitting your micro-nutrient and fibre needs for good health.

Too many people, too often, major in the minors. Instead of spending the time to count calories, they'll go to the nearest GNC store to find a fat burning supplement that just simply won't work. Again, using pyramids helps you pin point which areas of training or diet to focus on, and which areas are details.

Building a base

The bigger base you build, the higher potential peak you can have. This holds true for performance training and performance nutrition. Athletes and trainees are often impatient and believe they'll progress faster than everyone else. They'll use professional athletes as examples of why to follow the most-intense training program, why they should specialize in their sport early on into their athletic career, and why they should use the most advanced training methods.

They're wrong.

Professionals and high-performers often do NOT specialize early (they play multiple sports growing up and dabble in many different types of training methodologies) and they MASTER THE FUNDAMENTALS!

Using the strength training pyramid for example: trainees make the mistake of spending their energy on intensity, volume and frequency before they develop proper movement quality. Improving technique and movement quality will make everything upstream more effective.

Good movement quality will open you up to a wider array of exercise selections, create consistency and accuracy in your periodized program, as well as set you up for proper strength progressions and ultimately, more advanced training methods.

started from the bottom now we're here

Don't forget about the basics, master the fundamentals and you'll achieve more results than you originally expected, I promise. There's nothing wrong with learning about advanced training or dieting methods, however, if you're a beginner or intermediate trainee, keep things simple and practical.

Do I Eat Less Or Exercise More For Fat Loss?

Do you reach your fat loss goals by eating less or should you stick with your current diet and increase energy expenditure by exercising more? Let's go over each strategy and see what works best.

Do you reach your fat loss goals by eating less or should you stick with your current diet and increase energy expenditure by exercising more? Let's go over each strategy and see what works best.

Eating Less While Paying Less Attention to Exercise

Weight loss occurs when you consistently consume less calories than you burn; I'm sure everyone is aware of that by now. By tracking your calories and overhauling your diet with healthy whole foods, plenty of protein, fibre and vitamins, you will definitely lose weight. Some people are under the misconception that decreasing calories means eating less food; these are the same people that have problems managing their hunger levels - possible causing them to overeat or not adhere to their diet properly. The best way to control hunger levels while staying in a calorie deficit is to consume high volume foods, increase their protein intake and increase their meal frequency.

Examples of high volume foods include big salads, or substituting vegetables for your rice or pasta dish. Increasing protein intake can help with satiety and is achieved by consuming lean protein sources like lean beef, some seafoods, and vegetarian sources like tofu. A higher meal frequency, while shown not to have any beneficial effects on weight loss compared to a calorie-equated low meal frequency diet, can help people adhere to their diets more effectively and decrease the likelihood of overeating. Small to moderate size meals throughout the day can be better for diet adherence than eating 2-3 big meals a day.

What's wrong with this approach?

While you are certainly going to experience some weight and fat loss by eating less calories and improving your diet, your fat loss will plateau without paying extra attention to exercise. In order to consistently lose fat, your calories will have to decrease more and more. This is not only difficult in terms of managing hunger levels, but can be out right unhealthy - I've heard stories of females eating 1000 calorie diets attempting to lose weight. This is NOT okay and people will run the risk of nutrient deficiencies and low energy levels.

EXERCISE MORE WITHOUT CHANGING YOUR DIET

Exercise will do wonders for your body. Increased energy/calorie expenditure, improved nutrient partitioning (positively change the way your body deals with the nutrients and calories coming into your body), improved muscular and cardiovascular health, alleviate pain and prevent injuries. I recommend a combination of resistance training and cardio exercises for everyone, the most important thing is to make exercise sustainable and enjoyable.

My general recommendations for resistance exercise (lifting) would be a minimum 2 times a week. Cardio training can be done everyday (low intensity) or 2-3 times a week if performing challenging interval training. Doing that alone will increase your weekly calorie expenditure... as long as you're consistent!

What's wrong with this approach?

If you're a beginner trainee and you currently eat diet high in calories, its unlikely you'll be able to work off a bad diet. A beginner simply doesn't have the work or recovery capacity to exercise enough to out work a bad diet. Increasing muscle mass improves your fat and calorie burning abilities. However, new trainees do not experience significant muscle hypertrophy until 5-8 weeks into a consistent weight training program.

What should you do then? The answer lies in between the 2 strategies.

the perfect fitness and diet lifestyle

The perfect recipe for fat loss utilizes both strategies mentioned above. You should know now that fat loss can be achieved through either #1: increasing calorie expenditure, or #2: decreasing calorie consumption. Trying to take extreme measures on any 1 method will often cause you to fall short of your goals. It's very difficult to adhere to a hard exercise program when you're new to resistance or cardio training, and it's very hard to make your diet sustainable if it includes very low calories or foods you don't like eating.

The solution

Instead of taking extreme measures, take small steps to improve your exercise habits, diet and learn the concept of NEAT (Non-exercise activity thermogenesis).

NEAT is one of the most overlooked aspects of calorie expenditure and fat loss. NEAT represents all the physical activity throughout your day that isn't considered exercise. How much you walk a day, how many chores you do, how active your job is, how long you spend your day sitting and being sedentary, all of these are included in your NEAT.

"I eat pretty well, I exercise 3 times a week, how come I'm still not reaching my fat loss goals?" - Bob

Well I'm sorry to hear that Bob, but it might be because you sit on your ass all day when you're not exercising. Bob is most likely not training hard enough for exercise to have any significant effects on his calorie expenditure. Paired with that fact that he remains sedentary when not at the gym, his metabolism remains relatively slow.

This is an example of a breakdown of the daily calorie expenditure of a person that exercises moderately but stays relatively active in their daily life.

- Basal Metabolic Rate represents the calories burned just by staying alive (based on bodyweight, height, muscle mass, anthropometric features)

- NEAT represents the amount of activity level in a day not related to dedicated exercise

- Exercise represents a dedicated time to which you hit the gym/go for a run/follow your training program

- TE of Food represents the thermic effect of food - the amount of energy spent digesting the food you consume

As a beginner, there is only so much exercise you can do before it becomes unsustainable or you can recover from without being injured or burnt out. Seeing how the thermic effect of food plays a very small part in your metabolism and basal metabolic rate is dependent on genetic and body measurement factors, increasing NEAT would be the next best option.

As an intermediate/advanced trainee, your work capacity develops and the calories that can be burned through exercise increases. NEAT eventually turns into moderate-high intensity exercise. Many of these trainees can "outwork a bad diet", however, it still takes discipline and proper training/dieting strategies to become the leanest, strongest and fittest version of yourself.

There are plenty of ways to increase your NEAT, and consequently, energy expenditure throughout the day. Here are a few:

- Every hour or so of sitting, balance that out with 5-10 minutes of stretching and moving around

- Create a daily step count goal and hit it every day

- Walk to the grocery store instead of driving there

- Go on the stationary bike or treadmill while watching Netflix or studying for your upcoming exam

- Go for walk when listening to music or audiobooks

- Dance in the shower (careful there)

Achieving your fat loss goals and improving your fitness lifestyle does not occur while taking extreme measures, rather, working on all parts of the equation - diet, exercise, NEAT and building sustainable habits.

Exercise more, improve your diet, move more.

Thanks for reading! Here a few articles to get you started with your fitness and diet goals:

What Type Of Dieter Are You?

Surprising Reasons You're Not Reaching Your Fitness Goals (Habit Building Article)

How Much Protein Do You Really Need?

How To Pack On Muscle - Diet Tips For The Hardgainer

Need extra help? Want to jump start your training or diet? Feel free to contact me for a free consultation!

What Type Of Dieter Are You?

Weight and fat loss can be achieved using different styles of dieting depending on your personality, eating habit, tendencies as well as how much knowledge you possess about nutrition and dieting itself. Are you a trainee motivated by quick results or are you a person that likes to take it slow and ensure sustainable weight loss?

Weight and fat loss can be achieved using different styles of dieting depending on your personality, eating habit, tendencies as well as how much knowledge you possess about nutrition and dieting itself. Are you a trainee motivated by quick results or are you a person that likes to take it slow and ensure sustainable weight loss?

1. The Shotgunner - Quick Weight Loss

The shotgun method is what I like to call diets that start out with a large calorie deficit, with that deficit decreasing as bodyweight drops. Why did I name this the shotgun method? Because like a shotgun, the initial blast is strong (large calorie deficit - ensures initial weight-loss) and can hurt the person if they're ill-prepared to handle the consequent recoil (junk food temptations, binge eating, etc).

This method works well for people who are motivated by quick results and find it difficult to adhere to a more conservative approach. For example, a person looking to lose a large amount of weight (eg: 30lbs) will start off with a 500+ calorie deficit (daily) and slowly reduce that to a 400, 300, 200 calorie deficit as the weeks progress and as body fat is being lost. As I believe protein intake should stay at an adequate level, most of the reduction from calories should come from partial elimination of carbohydrates and fats.

Pros

- Very effective for short term weight loss

- Initial stages can be very motivating for some individuals and help them adhere to future weight loss diets

Cons

- Large calorie deficits can be very mentally stressful

- Initial low energy and decreased performance in the gym or at a physical job

- The chance of the rebound effect is much higher, some dieters will use the initial weight loss to justify stuffing their face the following weeks... AVOID THIS AT ALL COSTS!

2. The Turtle - Slow And Steady

One of the more popular methods used in the past few years due to increasing research on food intake habits, willpower and weight loss sustainability. In contrast to the "shotgun" method, this style of dieting employs a conservative calorie deficit throughout the entirety of the weight loss period.

The caveat here is that dieters must be aware of their maintenance calories (I've talked about how to find out that number through estimations or tracking right here under section #3: Learn How To Count). So what's a conservative calorie deficit? A daily reduction of 200-300 calories coming from carbohydrates has worked well for me and my clients. Depending on your metabolism, expect to lose about 0.5-1lb per week. Trainees who employ this diet must be persistent and consistent with their calorie intake. If weight loss stagnates, consider increasing the amount of physical activity you do or further increasing the calorie deficit.

Pros

- The conservative calorie deficit allows dieters to lose weight without feeling the initial low energy that comes with large calorie deficits

- A small calorie deficit can sometimes be unnoticeable given the composition of your meals are healthy and based around nutritious and satiating, whole-foods.

- Paired with adequate protein intake, this style of dieting ensures maintenance of your hard-gained muscle!

Cons

- May not be suitable for beginners new to counting calories and portion controls

- Tests dieter's patience, weight loss may not occur for the first weeks either due to inaccurate tracking or using the wrong maintenance calories as a baseline

The Bottom Line

Both types of dieters can see success as long as they plan out their diet and adhere to it. Don't be quick to dismiss large calorie deficits and diets like the "shotgun method". While it doesn't always fit the modern dieting narrative that everything should be done conservatively to ensure long-term success, I've seen first hand that people can succeed with more daring weight loss methods. Pick the right dieting style that suits your goals and current level of experience with nutrition. Good luck!

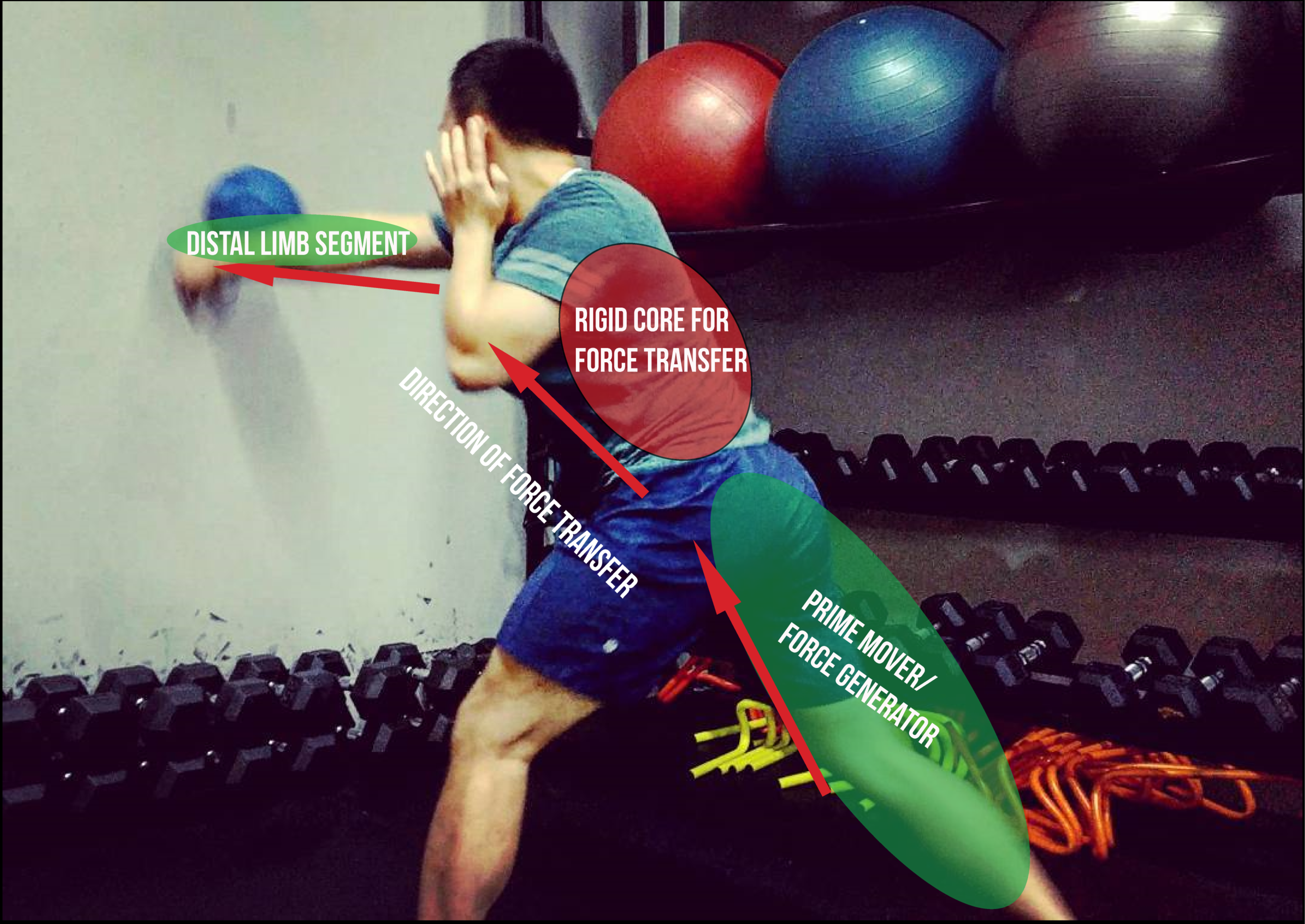

Medicine Ball Throws For Fitness and Power

Challenge your core strength and sculpt your oblique abs with these medicine ball throw variations!

There are few sounds as satisfying as a medicine ball slamming into a concrete wall. Whether your goals are to burn fat, increase your fitness or improve your sport performance, the use of medicine balls is a fun way to get you there.

I created this video showing you how many variations you can use. The non-rotational exercises will challenge your core strength while the rotational throws will blast and sculpt your oblique abs.

Add these to your circuit training or strength & conditioning routine and try them out! Enjoy!

How Functional Is Movement Training For Fitness & Performance?

With the rising emergence of “movement training” in both the fitness industry and high-performance athletics, it begs the question… Does movement training actually produce results?

With the rising emergence of “movement training” in both the fitness industry and high performance athletics, it begs the question… Does movement training actually produce results?

Here’s why you should probably take the hyped up movement training trend with a grain of salt, especially if you are focused on improving fitness and function. There are better ways to get fit, fast, strong and powerful, and they don’t involve becoming a functional training guru.

Defining The Un-Definable “Movement Training”

In order to clearly evaluate the benefits and pitfalls of movement training, we must first define the term. Unfortunately, there is no conclusive answer. The definition of movement training will differ from coach to coach, trainer to trainer, and athlete to athlete. Some may consider movement training the motor patterns and exercises specific to their respective sport, while others consider it the ability to express your body freely by adopting a multitude of complex movement patterns.

One of the most polarizing movement training specialists is of course Ido Portal, coach of UFC superstar Connor McGregor. So, what does he have to say about movement training? Ido describes movement culture as a “contemporary paradigm shift in physicality, moving us away from main culprits in movement and fitness as well as the separation between health, aesthetics, performance and art”.

Athlete and former UFC Interim Champion Carlos Condit has also been working with MovNat post-ACL injury. MovNat, much like the Ido Portal Method, believes in a “mindful approach to the full range of natural human movement abilities”.

Lastly, Naudi Aguilar from Functional Patterns is another name I can think of that falls under this category of “movement training”. I think we all know Naudi’s name by now after his explosion onto the scene after a rather fire filled exchange with the glute guy Dr. Bret Contreras a few short years ago.

Why’s Movement Training So Damn Popular In The First Place?

Movement training is becoming more and more popular in athletic performance and fitness mainly because:

Trainees are getting bored with traditional weightlifting exercises such as the squat, bench press and deadlift and seek more variation in their training

Trainees and the general population are buying into the touted benefits of movement training

Trainees have been convinced that traditional resistance training and rehabilitation exercises are “nonfunctional”

Let’s admit it. It looks pretty cool. People are drawn to ideas that are polarizing, different, flashy.

The Truth About “Functional” Training

Although it’s unfair to group the Ido Portal Method, MovNat and Functional Patterns together, they do have one thing in common. They do not believe that the current paradigm and landscape of movement is sufficient for sport performance and health.

The principle of specificity always plays a role when discussing anything performance or health related. Gurus who preach that movement training is all you need and anything in the sagittal plane sucks, is most likely trying to sell you a product by downplaying their competitors.

Many traditional weightlifting and bodyweight exercises (squat, presses, deadlift, cleans, snatches, pushups) all occur in the sagittal plane, but have been shown to be very effective for muscular growth and strength. In addition, these gurus often claim that these exercises are not “functional”.

This naturally leads us into the discussion of functionality, and the question…

What is functional? Do we really need to be rolling around on the ground or balancing on a wobble board?

Too many times have people defined functional training as exercises on a Bosu ball or on a balance beam. While these exercises may serve a function, functional training should be defined as exercises that meet the demands of a specific goal.

Balancing on a bosu ball may be functional to one population, while completely useless to another. For example, balancing exercises on unstable surfaces have shown to be effective for developing stabilizer muscles in injured populations or post-stroke patients. However, may be completely useless to a power athlete looking to improve strength and power as exercises done on unstable surfaces actually reduces force output and does not carry over to the field, court, or platform.

As Mel Siff once said “There is no such entity as a truly functional exercise, except for the actual sporting or daily movement that we are trying to enhance by training”.

So why train at all? The answer is improving skill transfer.

The point is to perform exercises that have a high amount of transfer to the movement or quality we are looking to improve, whether it be biomechanical, neuromuscular or metabolic. With that said, let’s evaluate how well movement training transfers to different populations, which populations can actually benefit from movement training and which populations should stay away from movement training.

Movement Training In Sports Performance

Athletes must practice and be able to perform a variation of movement patterns in order to prevent over-use injuries, and to develop weaknesses to improve sport performance. While I’m a believer that athletes should aim to progress beyond the traditional lifts (squat, bench press, deadlift, power cleans, power snatches), I’m not convinced exclusively performing movement training is the perfect solution.

The amount of movement variation that is required by an athlete depends on factors such as previous and existing movement base, type of athlete and type of sport. As an athlete, how much time should be allotted to movement training (if any at all…) and how much time should be allotted to sport-specific training and traditional strength & conditioning.

Optimizing sport performance is about pushing the human body and mind to the upper limits, as well as experimenting with different training methods. It would be foolish to state that movement training is completely useless or has no place being performed alongside a smart strength & conditioning protocol.

Contact Sport & Mixed Martial Arts Athletes

Running as a form of recovery or long slow distance (LSD) training is often utilized in various sport performance programs. However, the large eccentric component of running unnecessarily stresses the lower body joints and can hinder recovery. This is especially true for athletes in contact sports like MMA and rugby, or in sports that already have a large running component to them, such as soccer.

For this reason, water-jogging/running, swimming, cycling and other activities with concentric-dominant muscle actions are preferred over running. In this case, I propose that: movement training can replace road-work (running) as a form of integrated aerobic and mobility training.

Here’s How To Implement It With This Population:

Use a heart rate monitor (chest-strap preferred). Find or develop your own bodyweight movement routine that focuses on low-impact, and mobility-focused exercises (deep lunges with a chest-stretch/opener, Spiderman/alligator crawls, shoulder rolls, transverse plane rotation drills, etc)

Keep heart rate at 50-70% of your Max Heart Rate, for most people this is a heart rate of 100-135BPM (lower end for recovery, higher end for aerobic adaptations).The key is to keep heart rate under lactate/anaerobic threshold.

Perform this for 30-60 minutes, 1-2x a week. After training sessions and/or on rest days.

In this application of movement training, heart rate and work output is low enough not to interfere with recovery, all while challenging proprioception and putting muscles through a full range of motion. Movements utilized do not have to be specific to the sport, as we are only aiming to improve general aerobic adaptations and promote recovery.

Strength Athletes: Powerlifting, Olympic Weightlifting, Strongman

Powerlifters need enough mobility to hit depth on their squats, be able to bench press and deadlift safely. Olympic weightlifters need a good amount of mobility and flexibility to be able to catch barbell snatchs and clean & jerks in a deep squat position. Strongman competitors need enough hip mobility to pick up heavy stones as well as possess decent shoulder mobility to overhead press safely and effectively. Outside these exercises, strength athletes are not required to practice a plethora of movement patterns. Because of this, movement training can come in the form of maintaining joint and muscular health.

Here’s How To Implement It With This Population:

Movement specialists Max Shank and Hunter Cook have great routines for post-lifting or on off-days, which is comprised of taking all your body’s joints through its full range of motion.

Since the goals of strength athletes are so specialized – pack on muscle, improve strength and power on the main lifts, performing movement training may be a waste of time.

When it comes to cardiovascular conditioning for strength athletes, low intensity cyclical aerobic training like cycling or the elliptical machine may be the better option. MetCons can also be utilized for Olympic weightlifters and Strongman competitors.

Endurance Athletes: Triathletes, Runners, Swimmers, Cyclists

Many endurance sports are cyclical in nature, therefore implying low movement variation in competition and in training. Rather than utilizing movement training, endurance athletes should perform resistance training in conjunction with their endurance training program.

It is a common misconception that resistance training is detrimental for endurance performance or it somehow adds unneeded muscle mass to endurance athletes. However, it has been shown that resistance training can improve peak power output for short-event, anaerobic-endurance athletes as well as improve average power output and movement economy in longer-event, aerobic-endurance athletes.

General Health and Fitness Population

On the other hand, improving physical health and fitness is about reaching or maintaining a healthy lifestyle in a safe and efficient manner. I stress the term efficient because people who fall under this category most likely are not professional athletes, therefore training needs time-efficient. Can movement training improve bone density, blood lipid profile or other health markers? Yes. Can movement training improve these measures as effectively as traditional resistance and cardiovascular training? I’m not sure it can.

For populations looking to improve overall fitness, lose fat mass and put on muscle mass; movement training exclusively, will likely not yield the same results as performing a combination of resistance training and cardiovascular exercise. Stick to multi-joint, compound exercises, while carefully selecting isolation exercises to improve your weaknesses or fix muscular imbalances.

Here’s How To Implement It With This Population:

The following movement patterns should make up the bulk of a well-designed resistance training program:

Hip Hinge Pattern (Deadlift, Kettlebell Swings)

Squat Pattern (Back Squat, Split Squat)

Lunge Pattern (Forward lunge, Lateral Lunge)

Horizontal Push (Bench Press, Push Ups)

Vertical Push (Overhead Press, Landmine Shoulder Presss)

Horizontal Pull (1 Arm Dumbbell Row, Bent Over Barbell Row)

Vertical Pull (Pull Up, Chin Up)

Loaded Carries (Farmers Walk, Sled Pull/Bear Crawls)

Isometric Core Exercises (Forearm Plank, Side Plank)

Anti-Rotation Core Exercises (Pallof Press, Bird Dog Variations)

Performing variations of these exercises will help you develop stability, muscle mass, strength as well as build a well-rounded physique. Familiarize yourself with these movement patterns, progressively overload them, and form a solid base before dabbling in more complex movements like muscle-ups or dragon pistol squats.

When it comes to cardiovascular conditioning, 30-90 minutes of steady state aerobic training at 50-70% of your Max Heart Rate (100-135BPM for most individuals) as well as 10-20 minutes of moderate to high-intensity intervals can greatly improve cardiovascular health and aid in fat loss while performed in conjunction with a resistance training routine.

I say in conjunction because I believe everyone should strength train. Strength training puts on muscle mass. Muscle mass plays a role in whole-body protein metabolism, preventing pathologic conditions and chronic diseases such as sarcopenia, and is associated with longevity and lower mortality rates.

The Bottom Line About Movement Training

In terms of building muscle and strength, and improving overall fitness: progressive overload is king. The lack of clear cut progressions in movement training, the inability to load certain movements safely, and the inconclusive definition of the term itself makes it hard to implement effectively in populations seeking to improve general health and fitness.

Should we as humans aim to improve our flexibility, mobility and movement? Yes of course.

Should we spend time touching butts at the park (movement training reference) at the expense of exercises like squats, presses and deadlifts that have already proven to be effective for fat loss, muscle gain and strength? Probably not.

Movement training should be reserved for populations that already have an athletic base, whom are looking to promote recovery, improve mobility, balance and overall movement variation whether it be out of personal interest, or part of a strategically designed strength & conditioning program. For trainees looking for a safe and effective method of increasing their fitness and improving their health, stick to the basics.

Great Core Exercises You're Not Doing #1

Planks and crunches getting boring? Challenge your stabilization and strength with these core exercises you've probably never done before.

Core training is very popular in the field of fitness and strength & conditioning. Along with popularity, comes a lot of misinformation. Core training is more than just doing 1000 sit-ups or crunches hoping your 6-pack will show up the morning after. When core training is done properly, it can be a great way to alleviate lower back pain, reduce chances of injury during sports or daily living activities, as well as give you a strong and resilient mid-section.

I’m sure you’re familiar with planks and hanging leg raises… so what other core exercises are there? I’ll show you a few!

Front Rack Holds

Front rack holds, aka standing planks (that’s what I call them anyways…). Tired of doing regular planks? Try these out.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Use a cross-arm or Olympic-lifting grip

- Keep arms and elbows parallel to the floor

- DO NOT flare your rib cage or chest out

- Tighten your core, engage your glutes and grip the floor with your feet

- Hold for time, take deep breathes intermittently

The great thing about this exercise is being able easily control the load to your liking. The down side is that beginners might find this position uncomfortable on the collar bones or upper chest. In that case, a goblet hold may be a better variation.

Suitcase deadlifts

Yup, this exercise is what it sounds like: picking up a very heavy suitcase. As opposed to a trap bar deadlift where both sides of your body are loaded, suitcase deadlifts challenge unilateral core stability. The goal of this exercise is to prevent your torso from leaning to one side as you lift the weight up. Along with challenging your oblique abdominal muscles, it’s a great way to strengthen your grip.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Hip hinge and squat down to grab the weight

- Control the weight on the way up and on the way down

- Don’t allow your torso to lean excessively to any one side

Uneven farmers walk

If the farmers walk and the suitcase deadlift had a baby, this would be it. The goal of this exercise is to walk straight and to avoid excessive leaning as we are trying to improve core stabilization.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Start off slow to develop stability, increase the walking speed after a few workouts/weeks

- DO NOT flare your ribcage or chest out

- Tighten your core, engage your glutes and grip the floor with your feet with each step

- Pick a larger weight differential (between the 2 kettlebells or dumbbells) to make this exercise more challenging

Tire clean and hold

While this exercise does not exclusively work the core, the core is still very active in preventing your torso from collapsing during each rep. Unconventional, but fun.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Pick a lighter tire if you’re a beginner trainee

- Tighten your core, engage your glutes, push into the floor with your feet

- Hold the position for 3-5 seconds

Assisted Razor Curls

Is this an ab-rollout variation or is it a hamstring curl variation? Well, actually it’s both! I love this exercise, especially for hamstring injury prevention. As well as challenging your core, you’re putting your hamstrings on blast and working on that eccentric strength. You’ll need a partner to help you out with this one but it’s worth it. (Idea taken from Australian Strength Coach Lachlan Wilmot, thank you!!)

This is one of the more difficult core exercises to perform, so here are some pointers to keep in mind:

- Start the movement off with a hip hinge

- Progress this exercise by reaching further out or hold the position for time (isometric)

Give these exercises a try. Got any questions or feedback? Visit my Facebook and Instagram page down below and leave a comment!

Guilt and Shame: Motivation For Exercise and Gym Attendance?

Let's talk about exercise motivation and habit formation for a minute.

Photo Credit: Psypost.org & U.S Pacific Fleet

Today, I came across this article: http://www.psypost.org/2016/09/mens-hidden-guilt-shame-body-fat-can-fuel-gym-attendance-study-finds-44867

Body image, expectations and attitudes towards exercise is usually a topic for women in mainstream media. However, this article/study examines how feelings of guilt and shame in men affect their exercise habits and gym attendance. These are my thoughts:

"The researchers found that men worried about body fat were more likely than others to undertake spontaneous, unplanned work-outs – and warned that these ‘sporadic’ exercise patterns tend to be difficult to sustain over time."

Sporadic exercise patterns are better than no exercise at all. Some people/trainers may say: there is no harm in feeling a bit guilty for not hitting the gym, whatever gets you up and moving. I generally agree with this. In my experience, many guys need a little kick in the ass to get them started. Whether these exercise patterns can be sustained should be addressed AFTER someone has already started exercising. It is then a matter of habit formation, support systems (friends, family, workout partners) and most importantly whether they're seeing results or not.

"With the recent growth of ‘selfies’ and the return of muscle-bound Hollywood hero icons like Vin Diesel and Hugh Jackman, there’s a real risk that males may be more influenced to attend the gym more regularly and workout to a point where it becomes dangerous or detracts from their wellbeing."

Looking and feeling like Superman is a "real risk" I believe people shouldn't be afraid of taking. How many people do you know where their well-being is being threatened by regular exercise? Please note that many middle-aged celebrities are on some sort of testosterone-replacement-therapy. A guy in their teens, 20s or even early 30s can build a healthy physique and improve their health and well-being naturally. Exercise is also about balance. How can you fit exercise into your life without detracting too much from other areas such as work and family?

For others that have struggled with their body image and their fitness, I urge you not to take the role of the victim. Find a trainer, watch some Youtube videos, ask a friend to go to the gym with you. For the first few weeks, its okay to let the feelings of guilt and shame motivate you to get in the gym, on your bike, in your running shoes; or whatever gets you moving. Those feelings will go away as you start to change your perspective on exercise. A lot of people seem to forget exercise improves mental health as much as it does physically. What starts out as a sporadic exercise schedule will develop into what I hope to be, a healthy habit.

Thanks for reading!

Link to the study mentioned in the article: http://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/pages/articleviewer.aspx?year=2016&issue=09000&article=00024&type=abstract

P.S. One of the best articles I've ever written is on habit formation, and how to take advantage of your environment and support systems to reach your fitness goals. This article has a special place in my life as it combines my experiences with science to demystify the motivations and steps required to form a healthy exercise habit. Its all about stacking the odds in your favor.

Check it at my fitness colleague's website:

http://www.fitnesspollenator.com/2015/10/surprising-reasons-youre-not-reaching-your-fitness-goals.html

The ULTIMATE Guide To Building SUSTAINABLE FITNESS Habits

Article originally posted on Travis Pollen's website: http://www.fitnesspollenator.com/2015/10/surprising-reasons-youre-not-reaching-your-fitness-goals.html

Through years of experimental and observational research on human physiology and biomechanics, science has dictated the optimal way to train for specific fitness goals. The problem is, the most efficient route may not always be the most enjoyable -- especially for people new to exercise.

What often happens to beginners is that they begin to find their routine boring and monotonous. These people eventually fall off and stop working out all together; whether it’s due to boredom or a lack of progress/results. Now, much like science, where adherence is an important factor in experimental studies, adherence is also a crucial part of a beginner's long-term fitness success.

The Dual Process Approach

In order for a person to adhere to an exercise program, they must first have the intention of working out. Psychologists theorize that the strongest conscious predictor of behavior and adherence is intention (1). Does the person have an intention to lose weight? To get stronger? To run faster? The first step to exercising is being conscious about wanting to change their behavior. Psychologists have also proposed that the greatest unconscious predictor is habit (2). Habits are said to be automatic actions or responses to a specific cue. Together, they form what is called a Dual Process approach to exercise habit and behavior formation (3). The Dual Process approach proposes that both conscious and unconscious processes of the brain work in conjunction in order to successfully form a behavior.

Setting Goals – Intentions

Do you have a clear, conscious thought about exercising? Great, you have already formed an intention. But let’s get more in depth to make sure you take your first step towards exercising: setting goals.

Step 1) Evaluate your current lifestyle, what don’t you like about it? What areas in your life are problematic?

Step 2) Set long-term goals. This is what you dream about, losing 30 lbs of fat, putting 50 lbs on your bench press, being able to run a full marathon. Whatever your goals may be, write them down!

Step 3) Set a couple short-term goals. The word “short-term” can be ambiguous; does it mean within a 1-month time frame? 2 months? 6 months? I like considering short-term goals as the baby steps that you take towards your long-term goals. Some short-term goals might be

a) Finding a local gym and buying a membership

b) Planning your exercise frequency around your current work/school schedule (e.g. My short-term goal is to go to the gym three times a week. I will go after work on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for 45 minutes each session).

Make sure the goals that you are setting are realistic and sustainable (which helps with habit formation). Setting a goal to hit the gym before you leave for work isn’t realistic if you have to be at work by 8:00 am and it takes you an hour to drive there, especially if you’re not used to waking up at 5:00 am. (The exception here would be if you have a very tight schedule and can’t find an alternative time.) Setting a goal to lose 30 lbs of fat in one month is also not realistic, as it would likely cause you to resort to unhealthy and dangerous ways of losing the weight.

Habit Formation

Researchers suggest that there are four factors that contribute to habit formation: rewards, behavioral complexity, consistency and environmental cues (4). Let’s go over each factor, including suggestions for increasing your chances of forming long-lasting exercise habits.

Rewards

Operant conditioning (OC) often explains and drives many of our behaviors and psychology. The OC theory states that behaviors are controlled by consequences, specifically, through reinforcement and punishment (5). Reinforcement is a process that increases the frequency of the behavior either through a rewarding stimulus (positive reinforcement) or a removal of an unfavorable stimulus (negative reinforcement). Punishment, on the other hand, is a process that decreases the frequency of a certain behavior either through an introduction of an aversive stimulus (positive punishment -- yes, there is such a thing), or a removal of a favorable stimulus (negative punishment).

The following figure illustrates the breakdown of the OC theory.

Exercise is unique in the sense that you go through periods of positive punishment before you reach the stage of positive reinforcement. The physiological adaptations and side effects of exercise/working out (resistance exercise, especially) are usually muscle soreness and overall body fatigue, which is considered by definition to be positive punishment (because there is an introduction of unfavorable stimuli). These outcomes are unavoidable with exercise, but it is our body’s ability to adapt to these stressors that makes us better and healthier than we were before.

It’s important to fight the urge to give up and fall off the exercise program. The reason why we continue to exercise is that we know exercise is good for our health and that we expect results. So why do people quit after a few workouts? 1) They simply don’t experience the results they were aiming for, and 2) somewhere along their fitness journey, they decided that feeling uncomfortable, tired, and sore wasn’t worth it.

Getting a person to adhere to their exercise program (increasing behavior) is all about rewards (positive reinforcement). People’s exercise frequency and behavior increases when they start seeing their goals come to fruition in the form of fat loss, pain alleviation, increased mobility, etc. Knowing that, how do we increase the chance of positive reinforcement and maximize our rewards?

1) Education

Learning safe and effective exercise technique is key to maximizing your results and giving you the comfort of knowing that the exercises you are performing will move you towards your goal. Education is also important for setting realistic expectations. Knowing that it is physiological impossibility to gain 20 lbs of muscle mass in two weeks will save you frustration and disappointment when you realize that you look the same as you did before the past two weeks of “hardcore” weightlifting. People looking to lose fat mass may not see results until 3 weeks into exercising, whereas people looking to pack on muscle mass may not see results until 8-9 weeks of resistance training (depending on previous lifting experience).

2) Hire a knowledgeable personal trainer/coach

If you lack the free time to do your own research on health and fitness, it’s wise to hire a fitness professional to help you out. Unfortunately, it can be pretty hard to differentiate between a good and bad trainer (no, their physique doesn’t tell you much about their fitness knowledge). Read some reviews, and ask your friends or family members for a referral. Choosing a good personal trainer might also be a trial and error process.

3) Think long-term

Avoid programs like INSANITY, P90X, ab-blaster 9000 or any program that “promises” you results in a very short period of time. You will increase the chances of acquiring an injury, and the results you gain from these programs are most likely not sustainable. The truth is, you’ll most likely have to develop a good aerobic conditioning base, proper movement patterns, and flexibility before you can partake in high-intensity, high-impact, or heavy-loaded exercises. Ease your way into it and remind yourself that you’re in this for the long run.

Behavioral Complexity

The more complex the behavior, the more likely it will require conscious processes (6). Since the dual process approach proposes that habit is often created through unconscious, automated processes and cues, we must start off our exercise program with simple and easy-to-digest exercises. Although learning new exercise techniques does require conscious thoughts and increased body proprioception, it would be a much better idea to learn how to perform a bodyweight squat than it would be to learn a power snatch.

The complexity of the behavior (exercise in this case) is also related to self-efficacy. Exercises with a low complexity will boost our confidence as we believe we have more chances of succeeding it in (unconscious self-efficacy). This is why running, cycling, and hiking are more popular than resistance training or sports: they’re simple to do (plus the fact that they’re more accessible and convenient to the general population)!

Here are a few ways we can minimize behavioral complexity in hopes of maximizing habit formation:

1) Start slow and ease your way in

This relates to point #3 under Rewards. Building an aerobic conditioning base and learning simple movement patterns (squat, hip hinge, pushing, and pulling) will go a long way in helping you achieve your short- and long-term fitness goals.

2) Regressions and progressions

For bodyweight and resistance exercises, learn the regressions and progressions of each exercise (or hire a professional) so you can monitor your improvement and know how to reduce or increase the complexity of every exercise.

Environmental Cues

The environment also plays a big role in habit development, as it can “prompt or disrupt automatic behavior” (7). Contexts where we feel safe and comfortable will boost self-efficacy and greatly contribute to forming unconscious behavior. It’s hard for people with low self-esteem and social physique anxiety to participate in group classes or expose themselves to a whole gym. It takes time to realize that most people either a) don’t care about you or b) are willing to encourage you and help you achieve your goals. The rest are just assholes. So how do we control our environment for habit formation to work in our favor?

1) Choose an appropriate gym/health club

If you’re completely new to exercising, choosing a family-oriented health club may be the best decision. You will feel more comfortable and be around others with the same goals as you. Joining a hardcore powerlifting or bodybuilding gym (or any gym with an intimidating environment) would not be a good idea and may actually discourage you from going to the gym again. Also, picking a gym that is nearby will increase your chances of going (would you rather have a five-minute walk to the gym or an hour drive?

2) Partner training

Workout with your friend or family member. It’s a great way to hold each other accountable and motivate each other to reach your goals. You’ll feel more comfortable if someone you know is on the ride with you.