Training Session Structure, Single Leg Explosiveness and High/Low Training - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #1

This week’s questions and answers session covers topics such as training session structure, single leg training for power and explosiveness as well as high/low training categorization.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is your philosophy on the structuring of a training session?

The overarching goal behind structuring a training session is to optimize the training adaptations from each exercise within the given session.

First things first, any strength and conditioning training session for a combat sport athlete will start off with a warm-up. I utilize a “RAMP” warm up, the main goal is to raise body temperature, activate muscles, mobilize the joints and potentiate the athlete’s neuromuscular system system to reach the intensities seen in the training session.

The second order of training involves performing exercises that have require a high neuromuscular demand. These are usually high-velocity or high-force output exercises like plyometric jumps and medicine ball slams or heavy compound lifts. The reason why these are performed first is because these training modalities are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigued. In other words, athletes will not be able to reap in the benefits of plyometric and max-strength training if those exercises are placed near the end of the session.

Followed by this, are accessory exercises that are single-jointed or aimed at smaller muscle groups. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Conditioning, depending on the type, will usually be placed at the end of the session.

Here is an example of a full body MMA workout (performed descending order) following these training session structure principles:

RAMP Warm Up (Mobility flow, FRC, Core training, Bodyweight Jumps)

DB Weighted Plyometric Jump

Plyometric Push-Ups

Banded Zercher Squats

Barbell Overhead Press

Cossack Squats + Rotating Lower Back Extension Superset

Banded Rear Delt Flies + Bicep Curl Superset

Aerobic Power Intervals

Cooldown

There are some nuances to structuring a training session however, especially if you’re using methods like post-activation-potentiation or if you’re prioritizing certain power, strength or structural training qualities. I’ve written an in-depth article “Exercise Order - Principle for Sequencing A Training Session”. In this article, I also detail the principles of fatigability and prioritization to help you navigate training session programming. Check it out.

Question #2 - How do you develop single leg or staggered stance explosivity?

Single leg power is first built on a base of bilateral strength and unilateral stability. Before chasing power and explosivity in split or staggered stance movements, ensure that you have spent time building up your strength through squat, deadlift and split squat variations.

Moving forward, some of my favorite exercises for combat sport athletes include lateral bounding exercises, staggered stance kettlebell swings and staggered stance trapbar deadlifts (links included).

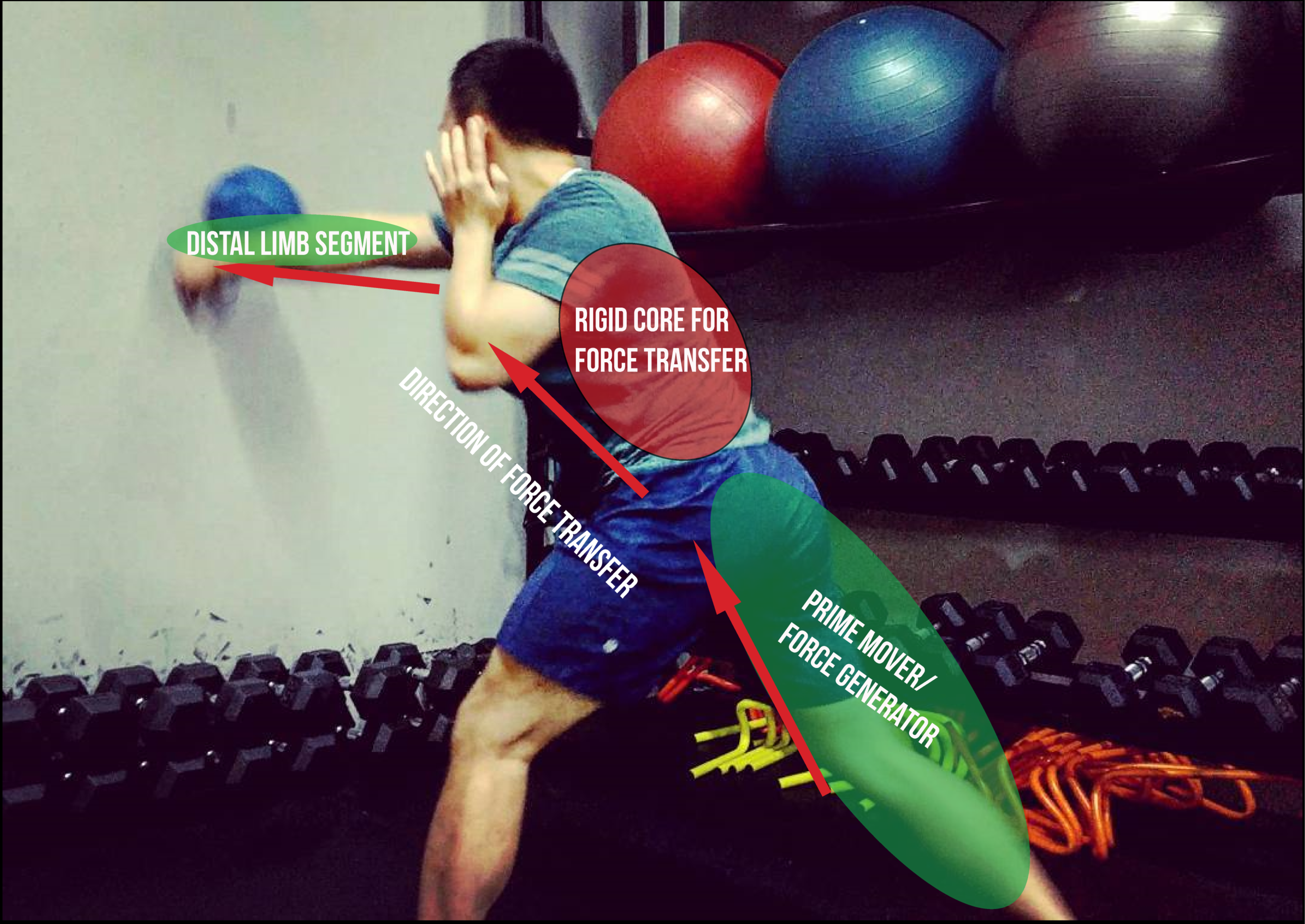

The reason I prefer these exercises is because of their ability to transfer over to both striking and grappling performance.

Lateral bounding variations develops lower body power in a way that compliments the in-and-out and angle changing agility demands of striking sports.

Staggered stance variations like kettlebell swings and trapbar deadlifts develops all of the strength and power qualities similar to it’s even-stance counterpart but puts extra emphasis on the back leg. By overloading the back foot and hip, it can possibly enhance force production in back-foot-driven grappling and striking movements such as shooting the double leg takedown or the power-straight and rear power-kick.

Question #3 - What happens if MMA workouts fall in between the high/low categorization of training you’re talking about in ebook?

Many training sessions or training days in reality will fall in between high and low. When this happens, I tend to side on the conservative side and count them as high.

The high/low categorization I mention in my ebook is simply a tool used to help us better understand and balance training stress throughout a training week. The important thing is to consider the training volume and intensity of each training session, the associated recovery cost, and how it will affect performance on subsequent training sessions or the next training day.

If you have a hunch a particular training session or class incurs much more stress than you originally thought, take some readiness data post-training and track fatigue markers like muscle soreness or nervous system readiness through jump or grip testing.

Remember, nothing in the chaotic world of combat sports training is set in stone. It’s great to have a framework to guide you, but this does not replace trial and error and constant refining of the training and planning process.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Optimizing The Warm-Up Using RAMP & Mobility Flows

The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

Its the general consensus that a warm-up is a mandatory component of any training session, no matter what sport or athlete you’re working with. The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

As a result of poor practices in the past, as well as noticing trends in the high-performance world, I remain unconvinced on the concept of needing to perform an overabundance of exercises to “activate” muscles or “mobilize” the joints prior to training. Banded distractions, foam rolling, all the bullshit that people waste their time on because “that’s how everyone else does it in the industry”.

I was unsatisfied and baffled over the fact that a warm-up could potentially take up 25% of the time out of a training session. The warm-up is the low hanging fruit in terms of programming improvements. Simple changes to the warm-up protocol afford coaches and athletes more time to put into more meaningful training that develops athletic performance.

Out of a necessity to make my personal coaching sessions run in a more smooth and efficient manner, I’ve created a mobility flow warm-up as a way to address the first 3 letters of RAMP within one series of exercises.

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

(R)aise body temperature

(A)ctivate muscles

(M)obilize joints

(P)otentiate to reach intensities seen in the training program

In this mobility flow, I’ve sequenced multiple foundational movement patterns together such as squatting, hinging, lunges, pressing and rotating. Alongside the obvious rise in body temperature from performing this, the emphasis on large range of motion movements and anti-rotational positions addresses both the “activation” and “mobilization” aspects of a warm-up, saving time that can be put into actual, meaningful training.

While this mobility is ground-based and has a lot more potential for additional exercises, the principles I work with remain the same - achieve rise in body temperature, put muscles and joints through a large range of motion and improve proprioception as quick as possible. Modify this flow as you see it fits your training demands.

After the mobility flow, some sort of potentiating training follows in order to reach the intensities seen in the training session (whether the session is strength-based, plyometric-based or concurrent). More details about exercise order and potentiation can be found in my exercise order article.

Application

This mobility flow can be performed as a warm-up, as a cooldown, or as an active recovery protocol.

Warm Up: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Cooldown: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Active Recovery Protocol: Multiple sets of 3-5 minutes, or one long set of 15-30 minutes (Keeping HR in Training Zones 1 and 2)

Great response from my athletes so far. Will be refining this over the next few months. I hope you enjoy it.

Best Strength & Conditioning Books For The Thinking Coach

Almost monthly, I receive the question - “What books on strength & conditioning do you recommend?”. And every month I list out several books off the top of my head that I think ANY strength & conditioning coach can benefit from. But the reality is, the content you should be reading will be determined largely by your experience as a coach thus far in your career as well as the education you’ve received up until now.

Almost monthly, I receive the question - “What books on strength & conditioning do you recommend?”. And every month I list out several books off the top of my head that I think ANY strength & conditioning coach can benefit from. But the reality is, the content you should be reading will be determined largely by your experience as a coach thus far in your career as well as the education you’ve received up until now.

What good is it if a novice coach reads a science-heavy Soviet training textbook on subjects he is unable to fully grasp and put into practice?

Before you dive into the list below, I should start off by saying that this list is in no way exhaustive. These are only books I’ve came across over the last 6-7 years, I am sure there are way more. Some of these I’ve read from front to back, others - I’ve only read several chapters of. There is also nothing wrong with reading “past” your experience level as the categories below were created fairly loosely and only act as a guider.

[UPDATED JANUARY 2020] Here are my recommended readings based on experience level:

The Novice Coach

Anyone that has just entered the strength & conditioning field as a coach… all the way to coaches with 1-2 years of professional experience working with competitive athletes. Ideally already possessing basic knowledge of training program design, movement pattern coaching and general physical preparation.

Exercise Physiology 8th Edition - Nutrition, Energy and Human Performance by William McArdle

Periodization - Theory and Methodology of Training by Tudor Bompa, Carlo Buzzichelli

Practical Programming For Strength Training by Mark Rippetoe, Andy Baker

Olympic Weightlifting For Sports by Greg Evertt

Scientific Principles of Strength Training by Mike Israetel, Juggernaut Training Systems

Ultimate MMA Conditioning by Joel Jamieson

Training and Racing With A Power Meter by Huner Allen and Andrew Coggan

The Hybrid Athlete by Alex Viada

Conscious Coaching - The Art & Science Of Building Buy In by Brett Bartholomew

Optimal Nutrition For Injury Recovery by Lyle McDonald

Applied Nutrition for Mixed Sports by Lyle McDonald

the experienced coach

A strength & conditioning coach with 2+ years of experience coaching amateur competitive and/or professional athletes in multiple sports. This coach is familiar with the underlying mechanisms of exercise physiology and movement, understands how to manipulate training variables in a periodized plan and is ready to learn more training methods to further augment specific training adaptations.

Supertraining by Yuri Verkoshanksky, Mel Siff

Shock Method by Yuri Verkoshanksky

Science and Practice of Strength Training by Vladimir Zatsiorsky

Block Periodization - Breakthrough in Sport Training by Vladimir Issurin

Strength Training Manual - The Agile Periodization Approach Volumes One & Two by Mladen Jovanović

Triphasic Training: A Systematic Approach to Elite Speed and Explosive by Cal Dietz, Ben Peterson

The Governing Dynamics of Coaching - A Unified Theory of Sports Preparation by James Smith

Applied Principles of Optimal Power Development - Max Schmarzo, Matt Van Dyke

The Veteran coach

A highly read coach that also possesses extensive experience implementing the knowledge and methods learned from the previous section. These type of coaches are ready to further challenge their own training philosophies by reading work on psychology and philosophy in order to improve. Readings in this section teach us how to be more efficient thinkers and be more aware of our own logical fallacies and cognitive biases when it comes to planning, implementing and coaching in the field of strength & conditioning. These books can be read concurrently with any of the above.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb Collection - The Black Swan, Antifragile, Skin In The Game, The Bed of Proscrutes

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Economy of Truth: Practical Maxims and Reflections by Vizi Andrei

Got some suggestions? Comment down below, I would love to know which books have been positively impactful in your career as a coach.

Balance The Grind Interview with Hao Nguyen

Had to pleasure of speaking to Hao from Balance The Grind about my career, launching GC Performance Training, balancing coaching and business responsibilities, the myth of work-life balance and plenty more.

Image by Hao Nguyen of Balance The Grind

Had to pleasure of speaking to Hao from Balance The Grind about my career, launching GC Performance Training, balancing coaching and business responsibilities, the myth of work-life balance and plenty more.

READ MORE @ BALANCE THE GRIND WEBSITE [LINK HERE]

8 Lessons Learned In The Field of Strength & Conditioning: A Coaching Reflection

What was originally planned as a journal for myself, I decided to edit and share with the world. As the title suggests, the list below consists of lessons I have learned throughout the years in the field of strength & conditioning and coaching. Many of them were unexpected and hard to bounce back from. But all of them made me a better coach at the end of the day.

What was originally planned as a journal for myself, I decided to edit and share with the world. As the title suggests, the list below consists of lessons I have learned throughout the years in the field of strength & conditioning and coaching. Many of them were unexpected and hard to bounce back from. But all of them made me a better coach at the end of the day.

I am an introspective person and this reflects in my job as a coach. I’m a big believer that introspection is needed in the path to self-improvement. 2019 is my 6th year working as a professional trainer and coach. Safe to say, I am still very young with a lot more to learn. I’m positive that this list will grow as I mature. Anyways, I digress. Let’s dive into it.

#1 Specific periodization methods and programming knowledge will only take you so far.

You need effective communication and interpersonal coaching skills. Your ability to break down the complex into simple and understandable bits that athletes will learn and retain, is very important. This is not to say programming knowledge doesn't matter. To break down the complex, you must understand it. Exercise physiology, biomechanics, transfer of training, are all core components of building a good training program. What takes it to “great” - what takes it to the next level, is the coach’s ability to implement the plan to his/her athletes.

A particular book I recommend, that I’m sure many of you have already heard of, is Brett Bartholomew’s “Conscious Coaching”. Excellent read, and a great start to becoming more understanding of the processes behind navigating and influencing the people you work with.

#2 There is no such thing as injury prevention - only injury mitigation.

All athletes get injured, from the amateur rec-league level, to the highest levels of elite sports. The root cause of an injury can be hypothesized by a couple schools of thought: some believe it’s only a matter of inadequate recovery, others believe it’s purely biomechanics and that “perfect” textbook technique some how prevents injury.

Injury risk is composed of multiple interconnected variables – the interplay of adequate recovery in between training sessions, volume load management, psychological stress management, biomechanics, and sometimes just pure luck.

For a coach to say they can control ALL the possible variables and prevent an injury, is bullshitting you. The job of the S&C coach and physiotherapist is to MITIGATE injury risk. An analogy I like to use is martial arts sparring/striking sports – whenever you throw a punch or a kick, you are exposed. Being offensive while not getting hit is then, is a matter of controlling the variables where you can – timing your opponent, creating and breaking patterns, setting traps. Be the most offensive you can, while mitigating the risk of being hit yourself. This is what strength & conditioning is also about. Putting athletes in the best position to perform optimally, choosing the best exercises and training methods available, while reducing the chance of injury.

#3 Get used to walking the thin line all the time.

What exercises should I prescribe? How much variation is too much? Is this program too specific? Not specific enough? Should I be using more external and internal cues or should I let the athlete explore? How long should the taper be to ensure athletic abilities are peaked but the athlete isn’t too fatigued heading into competition? These are ultimately the questions a coach will have to deal with throughout their career.

The one thing I have seen drastic improvements in myself as a coach over the years, is the ability to make these hard decisions in stressful circumstances, and be confident with my choice. Improving athletic performance is hardly a linear path. One must know when to back off, and when to step on the gas pedal. Knowing what to do comes from a unique mixture of intuition and textbook-knowledge.

It is also okay to make the wrong decision, it is inevitable. Just let that guide your decision-making in the future.

#4 – Contentment will be the death of you.

The day you’re satisfied with where your knowledge at; the day you’re satisfied with the results your clients are getting, is the day you should retire. If you’re serious about being the best trainer and coach you can be, you require on-going self improvement. This doesn’t always mean trying to learn new training protocols, or racking up on certifications. This means using the puzzle pieces/skill set you already possess and rearranging them in a different way to solve an existing problem in a different perspective.

This can also mean improving your interpersonal skills, learning how to connect with your athletes, learning how to create buy-in so that your training program can be that much more effective.

#5 – Watch your athletes play their respective sports.

Take it a step further, play their respective sport yourself. It is sad seeing a coach that is fully disconnected with their athletes’ sport because I believe there are more dynamics at play than just “strength” and “conditioning”. In order to excel and become an elite coach, I believe one needs to go beyond a textbook needs-analysis. I understand this may be challenging for coaches who don’t “Specialize” and coach athletes from various sporting backgrounds. But to be the best, and to diversify your skillset, step up to the challenge. Understanding the meta of the game/sport, and the culture of the players, will undoubtedly improve your role as a coach.

#6 – The definition of AN “Elite” trainer/coach isn’t what I thought IT used to be

An elite coach is not always defined by the athletes they produce, but the quality of service and commitment they put into their athletes. Of course there is a knowledge and skill gap difference between a coach who produces great athletes, and a coach that doesn’t. But the type of high quality coaching I am referring to are the trainers and coaches give their 100% each and every day to connect with their athletes on a personal level. The ones developing kids and high-school athletes in silence. The ones that get forgotten by the public because they don’t work with a professional team or athlete. The ones that don’t get nearly as much attention because they don’t have controversial things to say on social media.

High level coaching comes in many various forms and the idea of success looks different to different people.

#7 – Treat your own development as a coach similar to tHE development of an athlete

Widen the base before trying to specialize. Study nutrition, learn about the principles of physiotherapy, brush up on sport psychology concepts. Like I touched on earlier, there are more dynamics at play than just strength & conditioning. Human performance is an interdisciplinary matter. While nutrition and psychology may be outside the scope of practice, it is absolutely beneficial to be well-read in those topics.

Similar to many young aspiring strength & conditioning coaches, I started off wanting to train athletes and no one else other than athletes. I was not happy stuck training the general population, a population I saw as hard to teach and unmotivated to learn. I quickly retracted this negative, toxic mindset when I realized the learning experiences I received from working with so-called “non-athletes”.

Do the things you don’t want to do, to reap in the benefits you did not know existed.

#8 - Business and career development/planning is essential

And I wish someone told me sooner. I am speaking with the private training sector in mind since it is the field where I have the most experience in. Passion for the science of training and coaching is a must, but in most cases, is not enough to take you to where you want to be. Become financially literate, marketing-savvy and building a strong network re skills that must be prioritized. The more I communicate with more experienced, veteran coaches, the more I realize the importance. This is something I am continually improving on along side my coaching ability. Definitely a work in progress.

Your own self reflection

Now is a good time to reflect on your own training and coaching journey. What lessons have you learned this past year? What are the biggest improvements you have made since beginning your career as a coach and trainer? What would you tell yourself if you could travel back in time 1 year? 5 years? 10 years?

Hypertrophy vs. Strength Periodization: Thoughts on Linear vs. DUP Programming

Recently, there's been some discussion about the differences in periodization for hypertrophy/muscle gain vs. strength and I just wanted to clear the air and give my take on it.

Recently, there's been some discussion about the differences in periodization for hypertrophy/muscle gain vs. strength and I just wanted to clear the air and give my take on it.

"Strength and hypertrophy adaptations between low- versus high-load resistance training: A systematic review and meta-analysis"

Conclusions: Both low- and high-load training are beneficial for hypertrophy but high-load training is better for strength adaptations.

"Effects of linear and daily undulating periodized resistance training programs on measures of muscle hypertrophy: a systematic review and meta-analysis"

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5571788/)

Conclusion: Linear- and & DUP are both similar for muscle hypertrophy.

These 2 papers compliment each other more than people think.

Here's why:

HYPERTROPHY is an anatomical adaptation whereby your muscles grow in size as a result of mechanical tension, metabolic stress and muscle damage; each having different contributions to the muscle building process. ("The Mechanisms of Muscle Hypertrophy and Their Application to Resistance Training" by Brad Schoenfeld)

STRENGTH is both an anatomical adaptation AND skill, which takes into account the practice of specific motor patterns. When it comes to the "performance" aspect, strength is expressed through lifting a heavy load, so by the way specificity, high load training obviously transfers over better to strength performance.

Whenever you plan or organize training principles (periodization), you first look at how the body behaves to certain stressors (exercise physiology). If rep range is fairly irrelevant in terms of building muscle, it's pretty clear that a DUP set up where you vary intensities/weight on the bar from day to day would offer the same benefits, if not more, than a linear set up where you commit to a certain rep range/intensity for multiple weeks at a time.

From here, it is safe to say:

Low and high-load training works for hypertrophy given the same effort - therefore DUP-based training is a valid strategy for hypertrophy.

Strength is a skill, which is built on high-load training, and expressed through a withdrawal of stress; which is termed a taper/peak (performance = fitness - fatigue).

Periodization for hypertrophy comes primarily in the form of volume progression and effort management. Pretty simple.

Periodization for strength however, volume, intensity, frequency, and fatigue all must be managed more closely in order to address the aspect of skill and motor learning development, as well as maximum strength specificity and expression

Without getting into TOO much detail. Let's keep it at that for now.

Cheers!

My Thoughts on the FMS (Functional Movement Screen)

I recently had someone ask me whether getting the FMS certification was worth it. Like many questions, I answered... "it depends".

FMS Certification For Trainers & Coaches: Good Idea? Or Stay Away?

I recently had someone ask me whether getting the FMS certification was worth it. Like many questions, I answered... "it depends".

For those who don't know, the FMS (functional movement screen) is a fitness assessment created to look for "movement dysfunction". The FMS can be a good tool for new personal trainer and coaches to use as an initial assessment and as practice as they become more familiar with human movement. But becoming dependent on an arbitrary set of exercises to understand movement dysfunction and predict injury risk is something many trainers and coaches should avoid as they progress through their career.

Using pre-determined movements and quantifying movement quality is the complete opposite of conscious coaching and dismisses the idea of movement variability.

Conscious coaching requires adaptability and interaction.

Stop staring at your piece of paper; start watching your athletes and patients move. Figure out which movements are required in their sport or daily life because the definition of "functional" movement varies from sport to sport and one environment to the next. Talk to your athlete or patient about their confidence (or uncertainty) about particular body positions or movements. Design well-structured training programs that control for load, fatigue management, and injury reduction. Since your athletes and patients will most likely come from many different backgrounds, conscious coaching and assessment will do heaps more than some standardized test will.

This is not to say I'm against writing anything down. Notes should be taken when necessary.

Instead of writing: "Scored a 2 on the lunge test", a conscious coach will watch their athlete and note: "knee valgus during fast change of direction when running - check hip and leg complex and assess previous injury history and running/agility technique."

Some argue that the fact that FMS can be standardized to help sports teams. Several of studies have come out showing that their findings do not support the "predictive validity of the FMS" and that the FMS does "not relate to any aspect of athletic performance", so using an invalid assessment is stubborn and a waste of precious time, no matter how consistent it is. Can the FMS be useful? Of course. But consider the picture blow:

The FMS is 8% better than a coin toss. Let that sink in.

Like I said earlier, the FMS can be useful for new trainers and coaches. However, the end goal should be to acquire enough knowledge on human movement, motor learning, movement variability and training load to be able to consciously watch our athletes and clients. The FMS is not a game-changer and I would advise you to consider whether or not getting certified will help you towards your goals given your current experience level.

Be adaptable.

Periodization 202: Training Phases, Residual & Cumulative Training Effects

Periodization, the systematic planning of exercise and athletic training. It is one of the cornerstones of high level sports and physical performance and without it, training has no context and no direction.

This series will cover the big picture as well as dive into the small nuances of what makes periodization such an important topic to learn for any aspiring strength & conditioning coach or high performance trainer.

Periodization, the systematic planning of exercise and athletic training. It is one of the cornerstones of high level sports and physical performance and without it, training has no context and no direction.

This series will cover the big picture as well as dive into the small nuances of what makes periodization such an important topic to learn for any aspiring strength & conditioning coach or high performance trainer.

This third part will discuss cumulative and residual training effects as well as the phases of training (off, pre, in-season).

~1800 words; 8-16 minute read

Read Part 101: Introduction

Read Part 201: Training Variation

Read Part 202: Training Effect & Phases

Read Part 301: Review of Periodization Models

Read Part 401: The Complexities and Problems of Periodization Theory

Training variation recap

As discussed in Part 2 (201), training stimuli can be described to fit a general-to-specific paradigm, where specific qualities are movements, mental states and physical attributes that are seen in the sport or competition the athlete or trainee is preparing for; while general qualities are variations of sport-specific attributes that builds the base to allow specific qualities to flourish in the long-term. Along with this general-to-specific paradigm, some physical attributes and motor skills are thought to be better developed in a sequential manner; either from a general-to-specific or simple-to-complex paradigm. For example, muscle hypertrophy is thought to be better developed prior to maximizing strength and power potential while jump-landing mechanics are better learned before more complex plyometric drills.

The general-to-specific paradigm can be applied to various training and programming variables, from exercise selection, to intensity, volume and frequency. The amount of variation included into a training program differentiates one periodization model from another. Before we take a critical look at each periodization model, we have to understand training effects and the concept of training phases.

Cumulative & residual training effects

If we run long miles, we build incredible endurance. If we resistance train in high volumes, we experience muscle hypertrophy. When we provide a training stressor, we adapt and experience a training effect. But how come we don't experience muscle hypertrophy right after a training session? How come it takes weeks of training in the 1-5 rep range to get strong?

Training effects can be categorized into:

Immediate and Acute effects (the immediate effects of training are: muscle fatigue, energy depletion, increased blood flow to working muscles, immediate changes on blood pressure and heart rate, etc)

Chronic and Cumulative effects (increased endurance, muscle hypertrophy, increased strength and power, etc over the long term)

Residual effects (to what extent training adaptations deteriorate after bouts of detraining or deloading)

For the purpose of this article, we'll be discussing cumulative and residual effects as it pertains to periodization and programming.

The cumulative training effect refers to the changes in "physiological capabilities and level of physical/technical abilities resulting from a long-lasting athletic preparation" (source). Vladimir Issurin, an expert and innovator of Block Periodization, notes that there are functional limits to our body's physiological systems, some of which are more trainable than others. Changes in aerobic characteristics from endurance training such as mitochondrial biogenesis and muscle capillarization are more pronounced compared to anaerobic characteristics such as hydrogen ion buffering.

In contrast, residual training effects refer to how long these adaptations are maintained after an acute withdrawal of training volume load or absolute cessation of training. The table below shows the residual training effects of different physical adaptations:

The degree of detraining is dependent on several factors.

First, the duration of training before cessation. Residual training effects usually follow an analogy made by Vladmimir Zatsiorsky (author of The Science and Practice Of Strength Training) and Dr. William Kraeme: "soon ripe, soon rotten". This suggest that physical attributes that have been developed for a longer time, can be maintained for longer before there is a decrease in performance following a deload or periods of no training. In a similar view, Nick Winkleman and Issurin note that adaptations that result from a structural change, such as cardiac remodelling, muscle capillizaration and muscle hypertrophy last longer after detraining, compared to adaptations that occur on the enzymatic level such as anaerobic performance, hydrogen ion buffering and phosphocreatine storage. A great example of this in the strength training realm and one that many of you can relate to is the fact that many lifters and trainees are able to maintain their muscle mass even with prolonged periods of low volume, high-intensity training. Muscle mass loss is a fear many bodybuilders and fitness enthusiasts have. But if you've spent some quality time building that muscle and protein intake during periods of deload are high, chances are, it won't waste away as quickly or as easy as you think.

Secondly, the training age and experience of an athlete/trainee also plays a factor in training residuals. Older and more advanced level athletes tend to experience longer residuals because of their higher accumulated training time, in line with the "soon ripe, soon rotten" analogy.

Lastly, the intensity used during retraining or detraining loads plays a role in mediating training residuals as well. The use of moderate to high-intensity training slows down the rate of detraining, however, volume must be controlled in order to avoid disrupting the recovery process. Residual training effects are of extreme importance especially when using non-traditional periodization methods like block periodization or when managing the training loads for sports team athletes during the in-season or competition-period. Residual training effects also give way to the method of tapering, where volume is decreased to reduce fatigue and allow for the expression of fitness (Fitness-Fatigue Model).

An extreme example of this is a study carried out by Pritchard et al. 2017, where resistance trained males completed two 4-week training programs followed by either 3.5 or 5.5 days of training cessation. Following this deload (in the form of no training, NOT lowered volume), peak force in the bench press and mid-thigh pull increased above baseline.

Infographic Designed by @YLMSportScience

I will cover the concept of tapering and include some practical methods/recommendations in future articles.

Since not all physical abilities can be developed concurrently in a periodized program to the same degree, knowledge on the cumulative and residual effects enables coaches to prioritize certain performance measures, allowing them to make better strategic choices when planning a training program.

Phases of Training

One of the most agreed upon definitions of periodization is the division of training phases and periods within a training macrocycle. However, the names of these phases vary depending ont he sport, characteristics of the periodization model, and the philosophy of the coach.

Mesocycles/phases commonly follow the names: preparatory phase, competition phase and transitional/active-rest phase. The preparatory phase can further be divided into general preparatory phase (GPP) and specific/specialized preparatory phase (SPP).

PREPARATORY PHASE/OFF-SEASON

In GPP, the training variables are more general and varied in nature, stimulating a wide variety of physical attributes while during the SPP, variables and movements are more sport-specific, aiming to further prepare the athlete for competition.

GPP and SPP can be further broken down into extensive and intensive phases, describing the average intensities of that particular phase. An extensive phase will primarily consist of low-intensity, high volume training, using 50-70% of 1RM during resistance training (muscle endurance and hypertrophy) and working in Zones 2-3 in endurance training (aerobic). While an intensive phase will include a larger amount of medium to high-intensity training using training loads above 75-80% of 1RM and high intensity interval training for conditioning.

The preparatory phase is often called the off-season in seasonal, team-based sports like hockey, soccer/futbol, rugby, etc. This off-season or preparatory phase is where the most aggressive and creative periodization strategies occur to induce the most improvements in performance variables before a competition date or competitive season. Any weaknessess identified from previous training cycles or competitive matches is best addressed here, and any strengths should be further improved.

TRANSITIONAL-1 PHASE/PRE-COMPETITION/PRE-SEASON

After a preparatory training phase and prior to a competition date or competitive season, the volume load of training starts to decrease. This decrease is meant to achieve 2 things:

Reduce training fatigue so physical and mental attributes are peaked for the upcoming competition/season

Make time and room to accomodate the upcoming competition schedule, travelling schedule, media obligations and hone in technical sport-specific skills

This phase is called the transitional-1 stage, or the pre-competition phase or pre-season phase. Because of the length of many sports' in-season (lasting anywhere from 4-7 months depending on playoff eligibility), team-based sports should avoid any aggressive tapering methods heading into the competition season, and a more strategically planned maintanence program should be prescribed. This differs from climatic sports like many sports in the Olympics or combat sports like MMA and boxing where the athletes are preparing for a one-day/one-night competition. In those cases, aggressive tapers are necessary as there is less of need to maintain physical attributes post-competition.

COMPETITION PHASE/IN-SEASON

The competition phase, also known as in-season for team-based sports, is dedicated to maintaining specific performance variables such as strength and anaerobic conditioning in order to attenuate any detraining effects an athlete or team may experience. Knowledge of residual effects really plays a big role here. A coach needs to know how many hypertrophy-based, strength-based, power-based and conditioning-based training sessions are needed in order to maintain an acceptable level of fitness when their athletes are busy competing in matches, games and tournaments. A coach must also take into account what physical attributes are already being trained just by competing and playing in games. This may differ from position to position depending on the sport. A goalie in soccer will not utilize the same energy systems as a forward, a post will not have the same energy expenditure as a point guard in basketball. The most time and energy-efficient method of maintaining physical attributes must be performed when athletes have a full competition schedule.

TRANSITIONAL-2 PHASE/ACTIVE REST PERIOD

The transitional-2 or active-rest phase of a yearly training plan is dedicated to complete restoration of the team and athletes, both from a physical and mental standpoint. It is common for athletes to engage in physical activity or exercises that do not relate to their respective sports. However, exercises should be low-impact in nature and should not impede or jeopardize the recovery process if high performance is the goal. The main goal of the transitional-2, active-rest period is to withdraw physical and mental stress and pressure that accumulated from hard training and competition, in order to avoid overtraining and mental burnout.

Rinse & Repeat

When the athletes have undergone adequate rest, they are now ready to re-enter the preparatory training cycle or off-season. These phases or seasonal compartmentalization of training occur on the macrocyclic level, with each phase lasting several months (depending on the sport, of course). There are a few exceptions, like in combat sports, where competition dates differ year to year, usually controlled by fighter rankings, and business-driven promoter decisions. In these sports, rigid periodization models often fail in properly preparing the athletes for competition; therefore a more flexible approach to periodization and training programming must be used. In the next article of this series, we'll dive into specific periodization models and their defining characteristics.

5-Part Periodization Series Links:

Read Part 101: Introduction

Read Part 201: Training Variation

Read Part 202: Training Effect & Phases

Read Part 301: Review of Periodization Models

Read Part 401: The Complexities and Problems of Periodization Theory

Benefits of Including Cardio Into A Strength Training Routine

As a trainer and coach, there are many things I've gotten wrong in the past. This series will cover topics I've been wrong and misinformed about, how I changed my stance, as well as how my practical recommendations and advice have evolved over the past months and years in light of newer information.

Admitting to your mistakes is the first step to self-improvement. In the personal training, performance and nutrition industry, you either learn and adapt, or you get left behind. As a trainer and coach, there are many things I've gotten wrong in the past. This series will cover topics I've been wrong and misinformed about, how I changed my stance, as well as how my practical recommendations and advice have evolved over the past months and years in light of newer information.

Cardio Training

Avoid cardio at all costs.

The treadmill are for cardio bunnies.

Cardio will make you smaller and steal your muscle and strength gains.

When I first started to strength train more seriously, these were the quotes I saw all over the internet. The young lifter that I was, I followed this advice and worst of all, I bought into the anti-cardio mindset. During my time powerlifting, I even read some advice from a big name saying something along the lines of: "The best thing you can do in terms of recovery from powerlifting is sit on your ass, the more time you spend resting, the more strength you'll gain". Ridiculous right? Well, at the time it didn't seem too ridiculous to me.

I grew up practicing martial arts, I ran track in elementary school, I was an explosive, high energy athlete as a kid. My whole life I didn't believe I was good at prolonged low-intensity cardio, so I did everything I could to avoid it. I didn't leave my comfort zone, simple as that. After injuring myself through powerlifting, I wasn't able to do what I loved. I knew the rehabilitation process would take a long time. Something had to change.

If I truly wanted to become the best personal trainer and the best coach I could be, why am I neglecting cardio? Why am I neglecting the science of endurance training and conditioning? A lot of people call themselves strength & conditioning coaches, yet only know how to strength train; I didn't want to be one of those people.

That's when I bought my first bike. I put in the hours on the pavement, flats, uphill, downhill; I fell in love with endurance training and the challenges that come with it. Taking time off strength training and putting more emphasis on conditioning helped me grow as a trainer, and as a strength & conditioning coach. It taught me how to be unbiased when designing a training program, and how to take the best pieces from each modality of training (strength training and endurance training) while discarding the misinformation, myths and negative mindsets that come from the strength training-only and the endurance training-only cultures.

it's all about the mindset

As someones who's been through it AND studied the science, I get where this anti-cardio mindset comes from. Strength athletes are still not buying into the benefits of cardio. I understand there are other ways of improving general work capacity other than jumping on an elliptical or stationary bike. But the biggest problem I see is that many recreational strength athletes and so called "fitness coaches" are neglecting cardio all together, and it's a shame. Not only is this anti-cardio mindset detrimental to the physical and the cardiovascular health-related attributes of an athlete, I have seen it manifests itself in the form of mental weakness and laziness; lifters that complain about 8 rep sets, lifters that embrace the unhealthy and overweight strength training lifestyle, lifters that have to demonize other forms of exercise to feed their own ego. If you're a fitness trainer and you preach an anti-cardio minset, you're not taking client's health seriously.

Over the last few months, I've realized muscle mass, strength and conditioning are not mutually exclusive, and you should as well. I've taken inspiration from some of the best MMA fighters, "hybrid athletes" like Alex Viada to top level Crossfit athletes.

Low-intensity cardio training is a lifters best friend. Here are some benefits:

Increased blood flow into working muscles for recovery in between lifting sessions

Great for cardiovascular health (low intensity training induces adaptions in the heart that high-intensity training simply can't)

Act as an anti-depressant and improves mental health and short term memory

Can be used as a form of active-meditation

I'm not telling you to hop on the elliptical for a 2 hour aerobic training session, just perform some type of steady state training 1-2x a week and acclimitize your mind to longer, prolonged efforts of physical activity.

Practical Recommendation and Takeaways

Perform 30-60 minutes of steady state low-intensity cardio on rest days to improve blood flow and muscle recovery.

Feel free to use several modalities, you don't have to just stick with one. Here's an example:

1 Modality Training

Stationary Bike - 45 minutes at low-intensity, conversational pace3 Modalities

Stationary Bike - 15 minutes

Skip Rope - 15 minutes

Incline Treadmill Walk - 15 minutes

Much like strength training, progressions can be planned, intensity can be undulated throughout the week. Here's an example from 1 week of training

Workout #1 Moderate steady state

5 minute easy warm up, 45 minutes at 75% of your maximum heart rate, 5 minute easy cool downWorkout #2 Easy steady state

70 minutes at 65% of your maximum heart rate.

Steady state aerobic training can improve your mental game and mindset more so than your physical performance. Get comfortable with uncomfortable situations, be humble and be willing to do things out of your comfort zone to grow and improve as an athlete, no matter what the sport.

Most Effective Way To Improve Lifting Technique

Learn the most effective way to improve technique for strength sports/

MOST EFFECTIVE WAY TO IMPROVE LIFTING TECHNIQUE

In strength sports, lifting technique is one of the most important traits in creating a strong, injury-free athlete. Lifters of all levels and experiences will benefit from improving technique.

If you've ever lifted heavy, you'll notice at a certain % of your 1RM, your form starts to deteriorate. Let's call this the technical breakdown threshold (TBT).

For example, if your 1 rep max on the barbell back squat is 315lbs, and your form starts to breakdown significantly when you lift weights over 250lbs (~80%). 80% is your technical breakdown threshold.

Generally speaking, beginner and intermediate lifters will have a lower TBT compared to more advanced and experienced lifters. Case in point: Have you ever noticed that some top level lifters look relatively calm and controlled during 1 rep max attempts? While less-experienced lifters will show more form break down during 1RM attempts.

So how do we use the TBT to help us improve technique? Here's how to do it:

Volume Progression Right Below Your TBT

To improve technique and form over the long term, we must start right at, or right below your TBT. For most of you reading this, I recommend using a load 5% lower than your TBT and progressively overloading at that intensity by either increasing sets, or increasing reps over the span of a training cycle.

Using the same example above (315lbs 1RM), and a TBT of 250lbs (~80%), an 8-week training cycle might look like this:

Week 1: 3x5 @ 235lbs (75%)

Week 2: 3x6 @ 235lbs

Week 3: 3x7 @ 235lbs

Week 4: 3x8 @ 235lbs

Week 5: 3x5 @ 245lbs

Week 6: 4x5 @ 245lbs

Week 7: 5x5 @ 245lbs

Week 8: 1xTechnical AMRAP @ 250lbs

*technical AMRAP means performing as many reps as you can with acceptable form, be honest with yourself.

Let's Break It Down (No Pun Intended)

During Weeks 1-4, you'll be working with 5% under your TBT, which is 235lbs (75% of current 1RM). Each week you'll be adding 1 rep to each set. This slight increase in volume over the span of 4 weeks will allow you to practice and dial in your technique.

During Weeks 5-7, you'll be working with a weight JUST under your TBT (245lbs). By now, your form should have improved drastically (hopefully) enough to perform sets at 7-8 RPE at a weight thats near to your TBT. The goal here is then to be able to maintain proper form over the increasing number of sets.

On Week 8, you'll be performing a technical AMRAP @ your TBT (250lbs). Put the number of reps performed into a 1RM calculator... This will be your new max.

INCREASING FREQUENCY

Increasing frequency is another good way to increase volume of the lift you're trying to improve. For example, if your squat needs work, I recommend increasing your frequency to up to 3 times a week. You can work at different rep ranges on each day, but keep the intensity low. The more quality reps you can perform and the more bad reps you avoid, the better. Using the same 315lb 1RM in the examples above, 1 week of training may look like this:

Day 1: 3x6 @ 235lbs (75%)

Day 3: 3x12 @ 190lbs (~60%)

Day 5: 4x3 @ 235lbs (~75%)

The philosophy

These are only examples, as there are other strategies that can be used here. However, the overarching philosophy of this method should be:

Consistently working with a sub-maximal weight that you are comfortable with.

Keeping intensity relatively the same (below your TBT) and progressive overloading by increasing reps or sets, NOT intensity (weight).

Spending plenty of time performing reps at the same intensity will make you more aware of technical changes and improvements from week to week.

Use this early on in your lifting career or ASAP if form breakdown is an issue for you.

Use this in the "off-season" and not as preparation for a powerlifting meet.

Please note that the set and rep schemes listed above are specific to the % of 1RM at which technique breaks down in the example I used.

Coaching vs. Programming: Is There a Difference?

Is there a difference between coaching and exercise programming? What makes a good coach?

initially a note post on my Facebook Page

Wait, if you’re programming for an athlete, aren’t you coaching them? I don’t see it that way.

Programming is writing out a specific training or nutrition program to cater to an athlete’s goal, whether it be improving their powerlifting total or body composition, etc. A knowledgeable exercise physiologist or personal trainer will be able to control training parameters well enough for their athletes to reach their goals effectively but a coach’s role extends beyond that.

Along side programming skills, a coach must be able to:

- Work WITH the person, not on.

- Dictate the training process and outline process-oriented goals

- Ensure that the athlete is tune with the process. So much can be learned working with a coach compared to jumping on a cookie cutter template program... HOWEVER, it is not uncommon for athletes to perform better on a cookie cutter program (over-individualization is problematic, more on this in another article).

- Effectively communicate with the athlete; this means communicating in a way the athlete can best understand what you expect out of them and what you’re teaching them

- Create curiosity in athletes, encourage questions and appropriately answer them (not just a “I’m the coach, you’re doing this cause I say so”)

- Understand that training and performance is multi-factorial, and that your athlete experience multiple stressors out of your control

- Care about their athletes. If you don’t give a shit about your athletes or clients, just write a training template and sell that. Simple as that.

A Lifter's Best Friend [PART 1]

Sorry, we won't be talking about dogs! Fortunately, these tools will help you take your training to the next level.

Whether you're a bodybuilder, powerlifter, Crossfitter, Olympic weightlifter or strongman, there are always tools to help you reach your goals more effectively. Aside from perfecting your technique and consistently training hard and smart, the following is a list of the best sidekicks/pieces of technology that can make a lifter's life easier and their training process more fun and effective.

1. A Coach

It doesn't matter if you're new to strength training, or if you're a seasoned lifter. Hiring a coach can eliminate any biases your own program may have. Even if you're well-versed in programming, having another coach adjust your programming variables or monitor your progress can add some objectivity and accountability to your training.

Benefits of working with a coach:

Objectivity, accountability in day to day training

Planned progression --> know when to go hard, know when to back off

Ability to learn from your coach --> pick his/her brain, don't be afraid to ask questions!

2. Cardio/Endurance Training

I'm very well aware cardio has been a controversial and often joked-about topic within the strength training community. Specifically, many lifters believe that performing any amount of endurance training will significantly hold back their powerlifting total and steal their hard-earned muscle mass gains: to the point where any mention of cardiovascular/endurance training in a strength training program can't be taken seriously among strength training circles. I'm not sure if this stems from laziness, a social stigma in strength sports, or just a case of misinformed lifters (I'd like to think the latter).

Without getting too much into detail about endurance and concurrent training in this post, the truth is: cardio will not steal your gains when done at the correct intensity and at the right time in your microcycle.

So how will cardio/endurance training help a lifter? Some benefits include:

Increased general work capacity --> which means less fatigue over the course of a training session, more sets and reps can be done in each training session over time

Quicker recovery in between sets

Great for promoting blood flow and recovery after training --> cooldown

Most importantly: mental health and cardiovascular (heart/blood vessel) health --> cardio can also be a form of active meditation (it is for me)

2.1. Heart Rate Monitor

As I mentioned above, cardio will not steal your gains when done at the right intensity. Similar to how weight on the bar is used to gauge intensity in strength sports, heart rate (beats per minute - BPM) is used to gauge intensity during cardio/endurance training. For a serious strength athlete looking to optimize muscle mass, strength, and power, LOW-INTENSITY steady-state cardio will be the best for maximizing aerobic adaptations without interfering with strength adaptations. Hard 30 minute runs or multiple sets of high-intensity intervals simply detract too much energy that could be used for strength training. Also, the recovery costs are also too high when performed on top of a dedicated strength training routine.

A heart rate monitor either in a watch-form or chest-strap will be useful for helping you pace/limit your intensity during cardio. The number to aim for is 55-70% of your Maximum Heart Rate for anywhere from 30 to 180 minutes (please note these values may change slightly depending on your level of fitness or any endurance sporting aspirations). The goal here is to work well below your anaerobic/lactate threshold; in layman's terms, work at an intensity where you can hold a conversation with the person beside you, and where you don't feel the burn in your muscles, as this may cut into your strength training recovery.

2.2. Bike/Rower

Ah, the bike and the indoor rower, the two things I like to call a lifter's best friend next to barbells and freeweights. The bike and rower are a much more favorable modality of cardio/endurance. training as they have less of an eccentric muscle action component to it compared to running. While running, the ankle, knee and hip joint take much more of a beating due to contact with the ground with every step you make. This stress from having to decelerate your whole body is potentially problematic, especially for larger lifters. Biking and rowing has less of a recovery cost compared to running and won't cut into recovery from your lifting session to a significant degree. However, if running is preferred, I recommend starting off at a slow pace for a short distance, slowly increasing distance as your running technique and joint health improves.

-- In Part 2, I will talk about :

personalized intensity charts for each of your lifts,

the value of good training partners,

as well as other tools to help track your progress and to aid in recovery --

Any questions? Comment below. While you're at it, feel free to give me a follow on Facebook and Instagram.

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)

![[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1559464401554-UTSFUHZQUTNOISFNVX1P/Daryyl-Wong-Court.jpg)

![Tapering & Peaking: How To Design A Taper and Peak For Sports Performance [Part 2 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501283047888-1OMY4OC27GHE81P94CPG/mountains-sport-nature-human-mountain-climbing-wallpaper-hd-black-1920x1080.jpg)

![Overreaching and Overtraining [Part 1 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501052506104-FOT7NYG35KYOVLK3J12R/crossfit.jpg)

![A Lifter's Best Friend [PART 1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1473812813105-P772BN3OYK45JFS4SDTR/crossfanatico.PNGcrossfanatico_0.PNG)