Do I Eat Less Or Exercise More For Fat Loss?

Do you reach your fat loss goals by eating less or should you stick with your current diet and increase energy expenditure by exercising more? Let's go over each strategy and see what works best.

Do you reach your fat loss goals by eating less or should you stick with your current diet and increase energy expenditure by exercising more? Let's go over each strategy and see what works best.

Eating Less While Paying Less Attention to Exercise

Weight loss occurs when you consistently consume less calories than you burn; I'm sure everyone is aware of that by now. By tracking your calories and overhauling your diet with healthy whole foods, plenty of protein, fibre and vitamins, you will definitely lose weight. Some people are under the misconception that decreasing calories means eating less food; these are the same people that have problems managing their hunger levels - possible causing them to overeat or not adhere to their diet properly. The best way to control hunger levels while staying in a calorie deficit is to consume high volume foods, increase their protein intake and increase their meal frequency.

Examples of high volume foods include big salads, or substituting vegetables for your rice or pasta dish. Increasing protein intake can help with satiety and is achieved by consuming lean protein sources like lean beef, some seafoods, and vegetarian sources like tofu. A higher meal frequency, while shown not to have any beneficial effects on weight loss compared to a calorie-equated low meal frequency diet, can help people adhere to their diets more effectively and decrease the likelihood of overeating. Small to moderate size meals throughout the day can be better for diet adherence than eating 2-3 big meals a day.

What's wrong with this approach?

While you are certainly going to experience some weight and fat loss by eating less calories and improving your diet, your fat loss will plateau without paying extra attention to exercise. In order to consistently lose fat, your calories will have to decrease more and more. This is not only difficult in terms of managing hunger levels, but can be out right unhealthy - I've heard stories of females eating 1000 calorie diets attempting to lose weight. This is NOT okay and people will run the risk of nutrient deficiencies and low energy levels.

EXERCISE MORE WITHOUT CHANGING YOUR DIET

Exercise will do wonders for your body. Increased energy/calorie expenditure, improved nutrient partitioning (positively change the way your body deals with the nutrients and calories coming into your body), improved muscular and cardiovascular health, alleviate pain and prevent injuries. I recommend a combination of resistance training and cardio exercises for everyone, the most important thing is to make exercise sustainable and enjoyable.

My general recommendations for resistance exercise (lifting) would be a minimum 2 times a week. Cardio training can be done everyday (low intensity) or 2-3 times a week if performing challenging interval training. Doing that alone will increase your weekly calorie expenditure... as long as you're consistent!

What's wrong with this approach?

If you're a beginner trainee and you currently eat diet high in calories, its unlikely you'll be able to work off a bad diet. A beginner simply doesn't have the work or recovery capacity to exercise enough to out work a bad diet. Increasing muscle mass improves your fat and calorie burning abilities. However, new trainees do not experience significant muscle hypertrophy until 5-8 weeks into a consistent weight training program.

What should you do then? The answer lies in between the 2 strategies.

the perfect fitness and diet lifestyle

The perfect recipe for fat loss utilizes both strategies mentioned above. You should know now that fat loss can be achieved through either #1: increasing calorie expenditure, or #2: decreasing calorie consumption. Trying to take extreme measures on any 1 method will often cause you to fall short of your goals. It's very difficult to adhere to a hard exercise program when you're new to resistance or cardio training, and it's very hard to make your diet sustainable if it includes very low calories or foods you don't like eating.

The solution

Instead of taking extreme measures, take small steps to improve your exercise habits, diet and learn the concept of NEAT (Non-exercise activity thermogenesis).

NEAT is one of the most overlooked aspects of calorie expenditure and fat loss. NEAT represents all the physical activity throughout your day that isn't considered exercise. How much you walk a day, how many chores you do, how active your job is, how long you spend your day sitting and being sedentary, all of these are included in your NEAT.

"I eat pretty well, I exercise 3 times a week, how come I'm still not reaching my fat loss goals?" - Bob

Well I'm sorry to hear that Bob, but it might be because you sit on your ass all day when you're not exercising. Bob is most likely not training hard enough for exercise to have any significant effects on his calorie expenditure. Paired with that fact that he remains sedentary when not at the gym, his metabolism remains relatively slow.

This is an example of a breakdown of the daily calorie expenditure of a person that exercises moderately but stays relatively active in their daily life.

- Basal Metabolic Rate represents the calories burned just by staying alive (based on bodyweight, height, muscle mass, anthropometric features)

- NEAT represents the amount of activity level in a day not related to dedicated exercise

- Exercise represents a dedicated time to which you hit the gym/go for a run/follow your training program

- TE of Food represents the thermic effect of food - the amount of energy spent digesting the food you consume

As a beginner, there is only so much exercise you can do before it becomes unsustainable or you can recover from without being injured or burnt out. Seeing how the thermic effect of food plays a very small part in your metabolism and basal metabolic rate is dependent on genetic and body measurement factors, increasing NEAT would be the next best option.

As an intermediate/advanced trainee, your work capacity develops and the calories that can be burned through exercise increases. NEAT eventually turns into moderate-high intensity exercise. Many of these trainees can "outwork a bad diet", however, it still takes discipline and proper training/dieting strategies to become the leanest, strongest and fittest version of yourself.

There are plenty of ways to increase your NEAT, and consequently, energy expenditure throughout the day. Here are a few:

- Every hour or so of sitting, balance that out with 5-10 minutes of stretching and moving around

- Create a daily step count goal and hit it every day

- Walk to the grocery store instead of driving there

- Go on the stationary bike or treadmill while watching Netflix or studying for your upcoming exam

- Go for walk when listening to music or audiobooks

- Dance in the shower (careful there)

Achieving your fat loss goals and improving your fitness lifestyle does not occur while taking extreme measures, rather, working on all parts of the equation - diet, exercise, NEAT and building sustainable habits.

Exercise more, improve your diet, move more.

Thanks for reading! Here a few articles to get you started with your fitness and diet goals:

What Type Of Dieter Are You?

Surprising Reasons You're Not Reaching Your Fitness Goals (Habit Building Article)

How Much Protein Do You Really Need?

How To Pack On Muscle - Diet Tips For The Hardgainer

Need extra help? Want to jump start your training or diet? Feel free to contact me for a free consultation!

Benefits of Including Cardio Into A Strength Training Routine

As a trainer and coach, there are many things I've gotten wrong in the past. This series will cover topics I've been wrong and misinformed about, how I changed my stance, as well as how my practical recommendations and advice have evolved over the past months and years in light of newer information.

Admitting to your mistakes is the first step to self-improvement. In the personal training, performance and nutrition industry, you either learn and adapt, or you get left behind. As a trainer and coach, there are many things I've gotten wrong in the past. This series will cover topics I've been wrong and misinformed about, how I changed my stance, as well as how my practical recommendations and advice have evolved over the past months and years in light of newer information.

Cardio Training

Avoid cardio at all costs.

The treadmill are for cardio bunnies.

Cardio will make you smaller and steal your muscle and strength gains.

When I first started to strength train more seriously, these were the quotes I saw all over the internet. The young lifter that I was, I followed this advice and worst of all, I bought into the anti-cardio mindset. During my time powerlifting, I even read some advice from a big name saying something along the lines of: "The best thing you can do in terms of recovery from powerlifting is sit on your ass, the more time you spend resting, the more strength you'll gain". Ridiculous right? Well, at the time it didn't seem too ridiculous to me.

I grew up practicing martial arts, I ran track in elementary school, I was an explosive, high energy athlete as a kid. My whole life I didn't believe I was good at prolonged low-intensity cardio, so I did everything I could to avoid it. I didn't leave my comfort zone, simple as that. After injuring myself through powerlifting, I wasn't able to do what I loved. I knew the rehabilitation process would take a long time. Something had to change.

If I truly wanted to become the best personal trainer and the best coach I could be, why am I neglecting cardio? Why am I neglecting the science of endurance training and conditioning? A lot of people call themselves strength & conditioning coaches, yet only know how to strength train; I didn't want to be one of those people.

That's when I bought my first bike. I put in the hours on the pavement, flats, uphill, downhill; I fell in love with endurance training and the challenges that come with it. Taking time off strength training and putting more emphasis on conditioning helped me grow as a trainer, and as a strength & conditioning coach. It taught me how to be unbiased when designing a training program, and how to take the best pieces from each modality of training (strength training and endurance training) while discarding the misinformation, myths and negative mindsets that come from the strength training-only and the endurance training-only cultures.

it's all about the mindset

As someones who's been through it AND studied the science, I get where this anti-cardio mindset comes from. Strength athletes are still not buying into the benefits of cardio. I understand there are other ways of improving general work capacity other than jumping on an elliptical or stationary bike. But the biggest problem I see is that many recreational strength athletes and so called "fitness coaches" are neglecting cardio all together, and it's a shame. Not only is this anti-cardio mindset detrimental to the physical and the cardiovascular health-related attributes of an athlete, I have seen it manifests itself in the form of mental weakness and laziness; lifters that complain about 8 rep sets, lifters that embrace the unhealthy and overweight strength training lifestyle, lifters that have to demonize other forms of exercise to feed their own ego. If you're a fitness trainer and you preach an anti-cardio minset, you're not taking client's health seriously.

Over the last few months, I've realized muscle mass, strength and conditioning are not mutually exclusive, and you should as well. I've taken inspiration from some of the best MMA fighters, "hybrid athletes" like Alex Viada to top level Crossfit athletes.

Low-intensity cardio training is a lifters best friend. Here are some benefits:

Increased blood flow into working muscles for recovery in between lifting sessions

Great for cardiovascular health (low intensity training induces adaptions in the heart that high-intensity training simply can't)

Act as an anti-depressant and improves mental health and short term memory

Can be used as a form of active-meditation

I'm not telling you to hop on the elliptical for a 2 hour aerobic training session, just perform some type of steady state training 1-2x a week and acclimitize your mind to longer, prolonged efforts of physical activity.

Practical Recommendation and Takeaways

Perform 30-60 minutes of steady state low-intensity cardio on rest days to improve blood flow and muscle recovery.

Feel free to use several modalities, you don't have to just stick with one. Here's an example:

1 Modality Training

Stationary Bike - 45 minutes at low-intensity, conversational pace3 Modalities

Stationary Bike - 15 minutes

Skip Rope - 15 minutes

Incline Treadmill Walk - 15 minutes

Much like strength training, progressions can be planned, intensity can be undulated throughout the week. Here's an example from 1 week of training

Workout #1 Moderate steady state

5 minute easy warm up, 45 minutes at 75% of your maximum heart rate, 5 minute easy cool downWorkout #2 Easy steady state

70 minutes at 65% of your maximum heart rate.

Steady state aerobic training can improve your mental game and mindset more so than your physical performance. Get comfortable with uncomfortable situations, be humble and be willing to do things out of your comfort zone to grow and improve as an athlete, no matter what the sport.

MMA Strength and Conditioning: Endurance and Energy System Training for MMA (Part 2)

In this series, I talk about everything related to strength & conditioning and training in the sport of MMA.

WRITE BETTER PROGRAMS WITH THIS FREE CHAPTER

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

read PART 1 here

Part 2: endurance and metabolic demands of mma

In this part of the series, I will give you guys an overview of the body's energy systems, discuss the metabolic needs of an MMA fighter, and then lay out different training methods to improve endurance specific to MMA.

Energy system overview

Strikes, takedowns, grappling, submissions. A wide variety of physical capabilities and a diverse range of martial arts skills are required to excel in the sport of MMA. Don't forget the power and the endurance needed to pull off fight-finishing techniques or to last the whole duration of the fight. We are capable of all these movements thanks to our 3 energy systems: aerobic system, anaerobic system and alactic/phosphogen system. The intensity and duration of our movements is what dictates which energy systems are used, and which substrates are used to fuel that energy system. Each energy system takes a different substrate (fuel) to create energy molecules called ATP (energy currency of our body) that is then used to contract our muscles so we can move. As you can imagine, the energy demands of a sprinter and marathoner have completely different energy demands.

3 energy systems are used in the human body: Aerobic, Anaerobic and Alactic.

The AEROBIC system (also known as the oxidative system) is the slowest acting energy system in our body, yet it is capable of creating the most energy. At rest, around 65-70% of your energy comes from the utilization of fat, 25-30% comes from carbohydrates, while less than 5-10% comes from amino acids (protein). As intensity increases, these percentages shift - carbohydrates become more important because of its quicker availability in the body. That's why you need adequate blood sugar (carb) levels when exercising or doing intensive activity. The aerobic energy system is the predominant system involved in exercise lasting 2-3 minutes, to hours and even days. The aerobic system (aero meaning air) requires oxygen to utilize fat stores (body fat) and carbohydrate stores (in your muscles and liver).

The ANAEROBIC system (aka the glycolytic system), is a faster acting system that can produce ATP even in the absence of oxygen. The downside to this faster ATP-production rate is that it can only breakdown carbohydrates as fuel and it creates a significant amount of lactate (commonly known as lactic acid). Lactate is correlated with exercise and performance fatigue, but the concept is often misinterpreted in the MMA and strength & conditioning world (more on this later). Exercise bouts of moderate to high intensities, lasting upwards to 2-3 minutes are mainly fueled by the anaerobic energy system.

The ALACTIC system (aka the phosphagen or phosphocreatine system) is the energy system capable of producing the most energy within the shortest amount of time. A fight-ending flurry or combination uses this energy system. The alactic system is different to the aerobic and anaerobic system in that it produces energy by directly breaking down the ATP molecule, bypassing the conversion of fats, carbohydrates or protein into ATP. However, our body has limited stores of ATP, therefore the alactic system is the quickest to fatigue and can only produce large bursts of energy for up to 10 seconds. Fully restoring phosphocreatine and ATP stores takes around 5-8 minutes; this restoration time can be influenced by strength & conditioning training, as well as the level of development of the aerobic and anaerobic system.

One misconception about energy systems is that each energy system completely turns on or off during various intensities and durations of exercise. Instead, all three energy systems contribute to energy production during all modalities and intensities of exercise. The relative contributions of each will depend on the velocity and force demands of the exercise bout or sport.

Another misconception is that the aerobic energy system is not used during mixed-type and pure anaerobic sports, when in reality the aerobic system can supply anywhere from 30 to 65% of the energy used in an exercise bout lasting up 2 minutes (800m running event for example).

Endurance and metabolic demands of mma

Professional fights are 3 x 5 minute rounds with 1 minute rest in between rounds and Championship bouts are 5 x 5 minute rounds with 1 minute rest in between rounds. Amateur fights are slightly shorter, generally 3 x 3 minutes or less. A 15 minute or 25 minute fight then, requires a full spectrum of endurance capabilities. A respectable aerobic energy system must be developed to last the whole duration of the fight, while the short, repeated bursts of high-intensity action require a degree of anaerobic capacity and neuromuscular-alactic power.

It's widely known that fights often end before their allotted time limit, either via a knockout (KO) or technical knockout (TKO) by strikes, or by submission (SUB). This differs from other sports such as hockey or basketball where the players are required to play the whole length of the game. In MMA, fighters have the unique ability to control how long the fight lasts. This has huge implications on training strategies as well as damage and concussion mitigation. A fighter could technically never train their conditioning and achieve all their MMA wins by first round knockout... But... we all know that strategy does NOT work against equally-skilled opponents; even the most brutal knockout artists can be taken into deep waters. Professional MMA fighters must have the appropriate amount of conditioning to last at a minimum, 15 minutes. Failing to do so will prevent you from competing at the highest level of the sport.

Let's dive into the details.

MMA consists of intermittent bouts of high-intensity actions, followed by periods of moderate to low-intensity movement or disengagement. By compiling data from other combat sports, Lachlan et al (2016) categorized the metabolic demands based on 2 categories, grappling-based demands and striking-based demands.

Grappling-based sports like judo and wrestling appear to have a work-rest-ratio of approximately 3:1 with work phases lasting an average of 35 seconds, while striking-based sports like kickboxing and Muay Thai have a work-to-rest ratio ranging from 2:3 and 1:2, with work phases lasting around 7 seconds on average. MMA sits in-between these values, with a work-to-rest ratio between 1:2 and 1:4 with work phases lasting 6-14 seconds, which are then separated by low-intensity efforts of 15-36 seconds.

Work-to-rest ratios describe the amount of time exerting energy vs. the amount of the time disengaging and "taking the foot off the gas pedal". The more intense and long the work is, the more rest is needed to restore energy.

It should be noted that the structure of a typical professional MMA bout has a true work-to-complete rest ratio of 5:1 (5 minute rounds, 1 minute breaks), while the work-to-active rest ratio inside each 5 minute round is determined by the tactical strategies and the skill set of the MMA athletes. Fighters described as "grinders" such as Michael Bisping or Nick Diaz will display a much higher work-rest ratio than more "explosive" athletes like Jose Aldo or Tyron Woodley.

There is clearly a tradeoff between power/explosivity (lol Dada 5000) and the ability to perform optimally for the whole duration of the bout.

The best fighters in the world like Demetrious Johnson or GSP are not only in peak physical performance in terms of power and endurance, but have a high enough fight IQ to determine when to engage or disengage during a fight, when to perform a fight finishing flurry, or when to back off.

debunking conditioning myths in mma

"MMA matches only last 15-25 minutes, therefore high intensity interval training is the only way to improve endurance and conditioning"

The most common training mistake amongst fighters. In order to build elite level conditioning, fighters must have a solid aerobic base with a well-developed capacity for anaerobic efforts. As I mentioned earlier, the aerobic energy system is responsible for re-synthesizing ATP after periods of high intensity bursts, therefore influences how fighters recover in-between rounds AND in-between fighting exchanges. Since the aerobic system is developed through low-intensity cardio training, many coaches and fighters overlook this critical piece because it is, incorrectly, seen as inefficient. Oddly, fighters will perform an unnecessary amount of high intensity training along with their MMA training; a recipe for overtraining, sub-optimal recovery and increased risk of injury.

There are multiple contrasting studies on whether the addition of more frequent high intensity endurance training yielded any performance improvements. Some researchers found athletes that don't respond well to high volume low-intensity training showed greater improvements when they increased their frequency and volume of high intensity training. However on the contrary, the benefits of performing more high intensity training in already well-trained athletes, are limited.

What seems to be more important is the sparing use of these high intensity intervals outside of MMA training. By the way of training periodization, and the principle of specificity, the majority of the high intensity intervals should be performed few weeks out before the fight. Performing a high volume of high intensity training year round hinders a fighter's ability to improve their skills and stay injury-free.

Less is more sometimes.

"Being inefficient with your energy in the cage/octagon results in lactic acid build up in your muscles, causing a fighter to gas"

There's definitely some truth to this statement. When fighters "blow their wad" (a la Shane Carwin vs. Brock Lesnar), they're unable to recover, even with the 1 minute break in-between rounds. Why?

During moderate to high intensities, lactic acid and hydrogen ions begin to accumulate as the supply of oxygen does not match the demands of the working muscles - this is the byproduct of the anaerobic energy system. However, another byproduct of this energy system is lactate (mistakenly called lactic acid by the general population). Lactate is closely correlated with fatigue, however: correlation does not imply causation. Lactate is the 4th type of fuel that can be used to restore energy, primarily happening within the mitochondria of cells - the same location aerobic metabolism takes place.

Another common myth is that lactate doesn't form until you perform high-intensity exercises. Lactate actually forms even during lower intensity exercise (because the anaerobic system is still active to a degree). The amount of lactate produced is very minimal; we are able to shuttle this lactate into our mitochondria via the Cori-Cycle and effectively reuse it as energy. During the later round of a intense brawl however, the rate of lactate clearance simply cannot match the rate of which it is produced, this is called the lactate threshold. The figure below shows how lactate is recycled as energy after being produced as a by-product of fast glycoglysis (anaerobic metabolism).

The lactate threshold also represents the switch from using predominantly aerobic metabolism, to anaerobic metabolism. This is where the mental toughness and resilience of a fighter becomes more important. The fighters with the ability to push through the pain while maintaining their martial arts technique, will likely be the winner. In order to effectively delay the onset of muscular and mental fatigue, the goal of every fight should be to increase their lactate threshold.

While a well-developed aerobic base is needed, specifically training around lactate threshold is what will most effectively increase a fighter's ability to perform anaerobic work.

"That fighter has a lot of muscle mass and looks jacked, he will definitely gas out or probably has poor cardio!"

Holding a massive amount of muscle mass can negatively affect endurance, but not always. More often than not, jacked fighters possess poor conditioning due to a combination of poor energy utilization/strategy during fights, and neglecting lower intensity work in the off-season or fight camp. Fighters that put on muscle quickly most likely have focused too much of their time on hypertrophic training methods like heavy squats, deadlifts, presses, etc.

Each muscle is covered by capillaries that provide it blood and energy. Fighters that neglect endurance work crucial for increasing mitochondria density and capillarization of these muscles will have poor conditioning. Muscle mass and elite level conditioning are not mutually exclusive. Fighters who have focused on increasing muscle mass over the long-term while concurrently using training methods to increase capillarization will achieve the best results.

Fun fact: Yoel Romero (despite the blatant cheating) who looks like a Greek god, has 5 third round finishes in the UFC. Fans are quick to point the finger at jacked fighters and call them out for having poor conditioning when it's not always the case.

TRAINING variables & METHODS FOR IMPROVING ENDURANCE IN MMA

Training Variables

Conditioning work outside the MMA skills training revolves around the principles of intensity, volume and frequency.

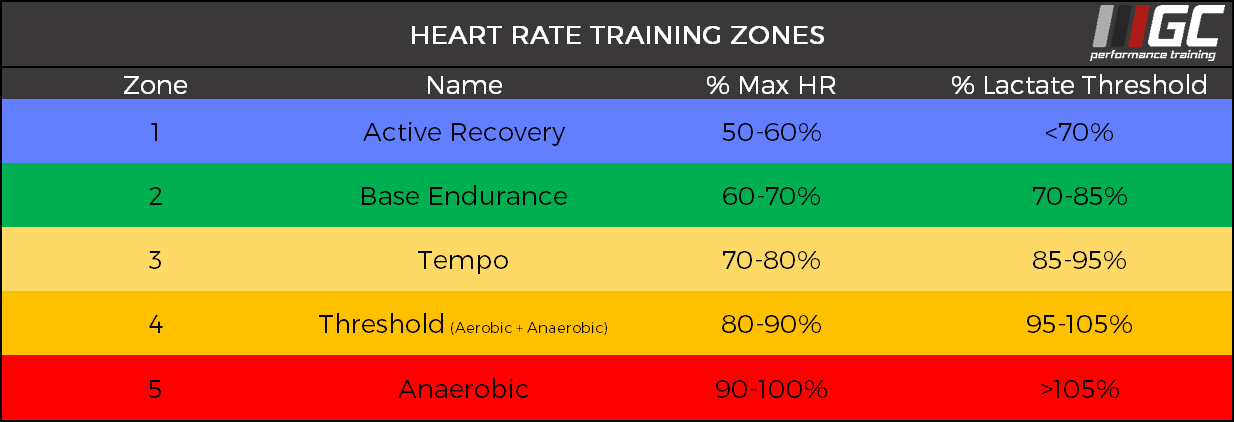

Intensity represents how hard or how close to maximal effort one is working. Maximal heart rate, lactate threshold, rate of perceived exertion (RPE) and power output can all be used to gauge endurance training intensity. Prescription of low, moderate and high intensity workouts are based on a percentage of these baseline or max values.

To make things simplier, intensity can be categorized into different training zones. In the chart below, training intensity zones are based off of a percentage of an athlete's maximal heart rate OR a percentage of their lactate threshold. Heart rate is well-known to have a linear relationship with exercise intensity, in that when workload or intensity increases, heart rate will also increase to supply the working muscles with blood.

Since lactate threshold represents the switch from aerobic to anaerobic energy production, using an athlete's lactate threshold is a more accurate method of prescribing conditioning work. For amateur fighters that may not have the access to equipment necessary to measure lactate threshold, heart rate is the next best option.

Volume indicates how much total work is being put into endurance training. In sports like running, cycling and swimming, volume will be represented by the total distance travelled during training. In team sports and sports like MMA, training volume is measured by using the "time in zone" method. How much time per training day or training week are we spending in each training zone? This will give us an idea on how much rest an athlete needs, or whether we need to push them harder to achieve the level of conditioning we're seeking.

Lastly, frequency indicates how often we are performing endurance training. Specifically, how many times a week we use a specific training method.

Breaking Down The Training Zones

Low Intensity

Zone 1 is commonly called warm-up or active recovery. This intensity is not hard enough for any surmountable enudrance to be developed, but enough to promote blood flow and therefore recovery to the working muscles. Training in Zone 1 primarily uses fatty acids for energy production.

Zone 2 is called base endurance or extensive endurance training. This represents the lower limits of the aerobic energy system and still uses predominantly fat as fuel. Training in this zone will promote higher cardiac output (heart pumps more blood), as well as the capillizarization of muscle fibres I talked about earlier.

Zone 3 is called tempo training or intensive endurance training. This zone challenges the upper limits of the aerobic system. Lactate production starts to ramp up at this Zone, however, there is no significant accumulation as intensity is still relatively low and clearance levels are still high due to the adequate of supply of oxygen to the muscles.

Moderate Intensity

Zone 4 is called threshold training. As the name implies, this training zone occurs near an athlete's lactate threshold (95-105% of lactate threshold). This intensity cannot be held for long, as hydrogen ions begin to accumulate. For this reason, training in this zone will improve an athlete's tolerance to pain/the burning sensation and will directly increase their ability to produce force and energy during muscle and mental fatigue.

High Intensity

Zone 5 often called anaerobic or VO2 max training, is considered true high intensity training. Training in Zone 5 is responsible for increasing an athlete's ability to produce force in a metabolically acidic environment. Paired with the large amounts of perceived exertion, the duration of which this intensity can be held is severly limited compared to lower and moderate intensity training.

Time In Zone

As alluded to earlier, the time in zone method is used to assess training volume. These are training times specific to improving an MMA fighter's conditioning

Zone 1 (Active Recovery) - Any where from 30-60 minutes to promote blood flow, joint flexilibility, muscle recovery. Multiple times a week, pre or post MMA training.

Zone 2 (Base Endurance) - 45-90+ minutes to improve the lower end of the aerobic energy system, increase muscle capillarization, improve aerobic enzymes, etc. 3-4 times a week.

Zone 3 (Tempo) - 30-60+ minutes to improve the higher end of the aerobic energy system. 2-3 times a week.

Zone 4 (Threshold) - 20-40+ minutes to increase lactate threshold and increase tolerance to muscle and mental fatigue. 1-2 times a week.

Zone 5 (Anaerobic) - 10-20 minutes in the form of high intensity intervals (work rest, work rest, repeat) to improve top end work capacity and power. Work intervals in this zone can last anywhere from 10 seconds to 90 seconds. 1-2 times a week.

PRactical training methods

Example Max Heart Rate: 200 BPM

Example Lactate Threshold: 165 BPM

Because I know my own lactate threshold, I'm basing my training zones off of that number.

Improving The Aerobic Energy System (60 minute workout - Low Intensity)

General Workout - 60 minutes total in Zone 2

Freestyle Swimming (20 minutes @ 115-140 BPM) *I like to aim for the middle of these ranges

Versa Climber (20 minutes @ 115-140 BPM)

Stationary Bike (20 minutes @ 115-140 BPM)

MMA Specific Workout - 60 minutes total in Zone 2 and 3

Shadow Kickboxing (15 minutes @ Zone 3 (141-150 BPM))

Skip Rope (15 minutes @ Zone 2 (115-140 BPM))

Takedown/Sprawl Drills (15 minutes @ Zone 3)

Rowing Machine (15 minutes @ Zone 2)

In both workouts, I'm using the most underutilized form of low intensity training - low intensity circuits. Instead of picking only 1 modality, let's say running, we're able to change the stimulus and muscles worked by switching exercises every 15-20 minutes. As long as we keep our heart rate in Zone 2, aerobic adaptations will be made. If we to only choose running, the endurance of our shoulders and arms would be neglected - not ideal for an MMA fighter.

The general workout is considered "general" because of it's lack of MMA-specific exercises. However, this is completely acceptable to do in the off-season. The MMA-specific workout can be utilized when a fighter comes closer to fight night. This shift from general to specific training is often seen in a well-designed, periodized training program.

Improving Lactate Threshold (30 minute workout - Moderate Intensity)

General Workout - 30 minutes total in Zone 4

Airdyne/Assault bike (10 minutes @ Zone 4 (156-173 BPM))

Active Rest - 2.5-5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Versaclimber (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

Active Rest - 2.5-5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Rowing Machine (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

MMA-Specific Workout - 30 minutes total in Zone 4

Heavybag Stand-up Work (10 minutes @ Zone 4 (156-173BPM))

Active Rest - 2.5-5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Partner Grappling/Clinch Drills (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

Active Rest - 2.5 - 5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Heavybag Ground n Pound (10 minutes @ Zone 4)

Threshold training can be done continuously, but because of the reasons stated above, I like switching it up and using a circuit style of training.

The name of the game here is pacing. It is easy to go a bit too hard on the heavybag or with grappling drills. Have a training partner monitor your heart rate so you stay in Zone 4.

Improving Top End Anaerobic Power (Multiple Intervals @ High Intensity)

General Workout

Hill Sprints or Prowler Push (4 x 20 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:6 work-rest ratio)

Active Rest - 5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Airdyne/Assault Bike (4 x 60 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:2 work-rest ratio)

Cooldown - 5-10 minutes @ Zone 1

MMA-Specific Workout

Heavybag All-Out Combinations (4 x 20 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:6 work-rest ratio)

Active Rest , Footwork - 5 minutes @ Zone 1-2

Heavybag Takedowns into Ground n Pound (4 x 60 second work: 2 minute complete rest) (1:2 work-rest ratio)

Cooldown - 5-10 minutes @ Zone 1

A wide variety of exercises could be used here. Get creative with your general and MMA-specific drills. The focus here is to work at 85-100% of maximal effort, and getting in a few minutes of complete rest. Power, explosion and the ability to end fights quickly is built here.

MMA Strength and Conditioning: The Role of S&C For MMA (Part 1: Introduction)

In this series, I talk about everything related to strength & conditioning and training in the sport of MMA.

Write better programs with this free chapter

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Introduction/Part 1

I spend a lot of time thinking about fitness, about strength & conditioning, about nutrition and about mixed martial arts (MMA). For those who don't know, MMA has been my favorite sport for the last 8 or so years. I love how raw the sport is, the amount of mental and physical preparation that goes into training and competing, as well as the movements and the culture itself. This series will not be as structured as I would like it to be, this is just a platform for me to elaborate on variables and methodologies I believe are crucial in creating a strength & conditioning program for fighters; some of which have been covered already, some of which, perhaps, haven’t been. I'll be providing sources and peer reviewed articles whenever necessary. With that said, lets dive into a brief history of martial arts and the creation of modern MMA.

Brief History

Practiced as a form of competition and for close combat conflicts, martial arts have existed for thousands of years. Professional modern mixed martial arts (MMA) however, has been in the mainstream eye for only ~20 years. Compared to professional ice hockey and football leagues (created almost 100 years ago), it is safe to say that MMA is still a young sport.

MMA initially exploded onto the scene thanks to the Ultimate Fighting Championship and their earliest competitions, pitting martial artists against each other from different disciplines to find out which martial art reigns supreme. Royce Gracie and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu proved to be the most superior at UFC 1, the first ever MMA tournament held by the UFC. After the famous, The Ultimate Fighter Finale fight between Forrest Griffin vs. Stephan Bonnar, MMA started to gain traction in the mainstream media. However, MMA hasn't been received all that nicely by all demographics. And you know what, it'll never be, seeing 2 athletes punch each other in the face or put each other in submission holds aren't for everyone. To this day, critics call the sport "barbaric" and liken it to "human cock-fighting". Ironic, because boxing was also once looked down upon for its aggressive nature and violence. It was not until the mainstream media and spectators learned more about to sport that it started to be called the "sweet science".

Compared to other sports, MMA's skill ceiling is ridiculously high. The skills of MMA fighters have drastically improved thanks to more education in the sport, and the growing community of fighters and coaches. We’re starting to see well-rounded martial artists and athletes and we're starting to witness techniques we used to see in old martial arts movie, like the karate-kid front kick, spinning heel kicks, and spinning elbows.

With the growing popularity of MMA, I really hope the sport will be more appreciated in the years to come.

Now, let's get down and dirty with the training side of things.

The Role of the Strength & Conditioning Coach

This is no longer the MMA of 1993, skills from many different disciplines of martial arts are needed to become a Top 3-5 fighter in any weight class. Strengths must be maintained and improved throughout a career, while weaknesses must be eliminated, or reduced enough to allow your strengths to shine. Positions, movement patterns, combinations and techniques that can be used in an MMA match are limitless.

Because of how novel strength & conditioning is in this sport, coaches are still trying to figure out the best exercises and training methodologies to build the best MMA athlete. Traditional endurance training modalities like running, or strength exercises like squats and power cleans may not always transfer well into the performance of a full contact athlete. The body types and skills in MMA differ greatly from fighter to fighter, there are no one-size-fit-all strength & conditioning protocols. Endurance and power drills must be tailored to the individual and must be prescribed in a way where it does not interfere with the skill acquisition of the athlete. A high performance coach must not forget that strength & conditioning training is only one piece of the puzzle. At the end of the day, MMA skills are the backbone of success in this sport.

The Goals of a S&C/Physical Preparation/High-Performance Coach:

1) Do not cause an injury to the athlete

2) Ensure the athletes physical attributes are peaked and tapered correctly going into a fight

3) Improve athlete-specific performance measures over time

4) Selectively pick exercises and training protocols that compliment the specific skill-set of the mixed martial artist

The Importance of Strength & Conditioning for MMA Athletes

Why do MMA fighters need strength & conditioning?

To develop physical capabilities that would otherwise be neglected or missed when exclusively performing MMA drills and sparring.

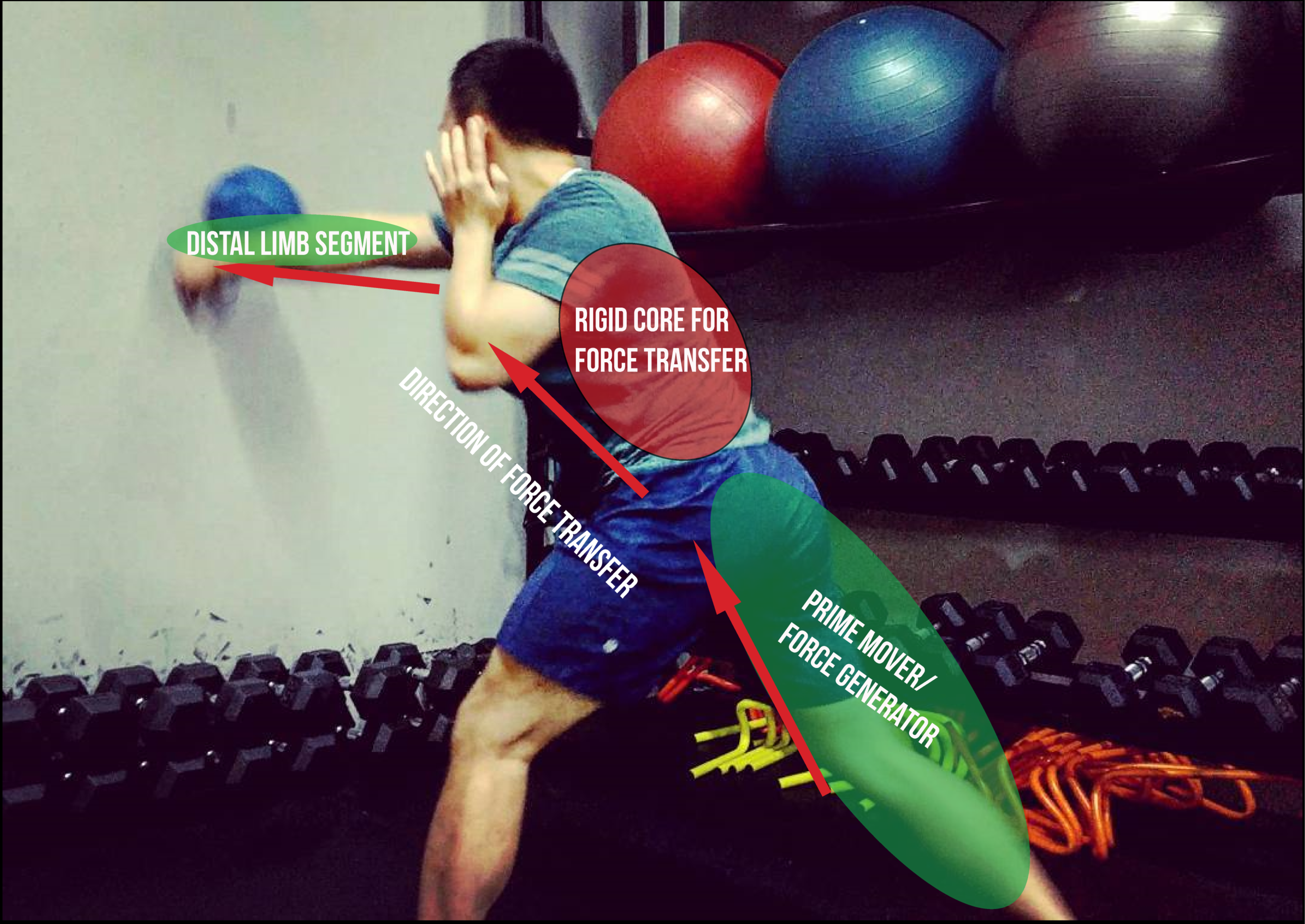

How does strength training improve performance?

The biggest benefits that come from strength training are increased force production and power, as well as injury prevention. I will be specifically talking about force production and power in a later part. Right now, I'll just dive into injury prevention.

Many muscle injuries come from the inability to decelerate a certain limb, or the inability to tolerate the forces produced when a muscle undergoes an eccentric contraction (EC). An EC happens when an external force is applied to a muscle, while the muscle fibers lengthen. Think of the lowering portion of a bicep curl, the deceleration/ground impact portion of a vertical jump, or the feeling in your quads while walking downhill. As long as we perform full range of motion resistance exercises and progressively overload them, we increase our ability to handle larger magnitudes of forces, especially at longer muscles lengths (where we're most susceptible to injury).

One of the most common injuries in professional sports are hamstring strains. Occurring in athletes from sports such as rugby, football, soccer and any other sport that requires running/sprinting. While the demands of MMA are much different and small strains and nagging injuries are bound to happen from rolling (Brazilian Jiu Jitsu) or sparring (striking), fighters can still learn from the modifiable risk factors involved in hamstring strains that are so prevalent in other sports in order to reduce chances of injury while training. These modifiable risk factors include sub-par functional muscle lengths, poor posture, strength and muscle imbalances and muscle inflexibility amongst others. Strength & conditioning practices should revolve around addressing these issues first, before focusing on increasing strength, power and endurance.

Isn't MMA practice enough for conditioning?

Yes and no, it depends on what training plan the head MMA coaches put their fighters through. Unless the head coach is knowledgeable on concepts such as heart rate monitor training, lactate threshold, cardiovascular training methods and periodization, a fighter's conditioning and physical preparation should be overlooked by a high performance coach. Much like how strength training should fill in gaps and address the weaknesses of a fighter, specific-conditioning work must be performed to optimize a fighter's gas tank on fight night.

Without getting too in-depth into the metabolic and endurance demands of MMA (I will cover this later in the series), conditioning must be done at the right intensity, at the right time, with the right amount of rest in order to induce the changes we want in a fighter.

Strength & Conditioning is useless?

Some MMA coaches don't believe in strength & conditioning outside of the skills training and sparring that fighters already perform. This may stem from stubbornness or undying tradition, I'm not quite sure. There are even elite fighters like George St. Pierre coming out and saying "I don't believe in strength & conditioning... I lift weight for looks". Ironically, GSP is known for being a pioneer in how fighters perform strength & conditioning routines. He was one of the first successful fighters to train in Olympic weightlifting and gymnastics during his fight preparation. I have a feeling these training modalities have contributed to increasing his power development, core stability and movement quality; although I could be wrong.

There is still some truth to what GSP is saying, however. Strength & conditioning should not be prioritized over skills training. A bigger, stronger, and more conditioned fighter does not always win, and we're reminded of that at almost every UFC event. Strength & conditioning is simply a platform and a preparation strategy that allows a fighter's skills to shine and allows them to develop those skills effectively and safely in training.

That's it for now. I'm interested in what you think, if you have any questions, opinions or insight, feel free to comment down below or contact me! In the future, I'll be writing about topics such as the metabolic/endurance requirements of MMA, how much hypertrophy and muscle mass plays a role, individualizing training strategies, training over-specificity, nutrition and more! See you guys in the next part!

PART 2 HERE

An Evidence-Based Approach to Hamstring Strain Injury (2009) by Mathew Prior et al.

Injury rate, mechanism, and risk factors of hamstring strain injuries in sports: A review of the literature (2012) Hui Liu et al.

Most Effective Way To Improve Lifting Technique

Learn the most effective way to improve technique for strength sports/

MOST EFFECTIVE WAY TO IMPROVE LIFTING TECHNIQUE

In strength sports, lifting technique is one of the most important traits in creating a strong, injury-free athlete. Lifters of all levels and experiences will benefit from improving technique.

If you've ever lifted heavy, you'll notice at a certain % of your 1RM, your form starts to deteriorate. Let's call this the technical breakdown threshold (TBT).

For example, if your 1 rep max on the barbell back squat is 315lbs, and your form starts to breakdown significantly when you lift weights over 250lbs (~80%). 80% is your technical breakdown threshold.

Generally speaking, beginner and intermediate lifters will have a lower TBT compared to more advanced and experienced lifters. Case in point: Have you ever noticed that some top level lifters look relatively calm and controlled during 1 rep max attempts? While less-experienced lifters will show more form break down during 1RM attempts.

So how do we use the TBT to help us improve technique? Here's how to do it:

Volume Progression Right Below Your TBT

To improve technique and form over the long term, we must start right at, or right below your TBT. For most of you reading this, I recommend using a load 5% lower than your TBT and progressively overloading at that intensity by either increasing sets, or increasing reps over the span of a training cycle.

Using the same example above (315lbs 1RM), and a TBT of 250lbs (~80%), an 8-week training cycle might look like this:

Week 1: 3x5 @ 235lbs (75%)

Week 2: 3x6 @ 235lbs

Week 3: 3x7 @ 235lbs

Week 4: 3x8 @ 235lbs

Week 5: 3x5 @ 245lbs

Week 6: 4x5 @ 245lbs

Week 7: 5x5 @ 245lbs

Week 8: 1xTechnical AMRAP @ 250lbs

*technical AMRAP means performing as many reps as you can with acceptable form, be honest with yourself.

Let's Break It Down (No Pun Intended)

During Weeks 1-4, you'll be working with 5% under your TBT, which is 235lbs (75% of current 1RM). Each week you'll be adding 1 rep to each set. This slight increase in volume over the span of 4 weeks will allow you to practice and dial in your technique.

During Weeks 5-7, you'll be working with a weight JUST under your TBT (245lbs). By now, your form should have improved drastically (hopefully) enough to perform sets at 7-8 RPE at a weight thats near to your TBT. The goal here is then to be able to maintain proper form over the increasing number of sets.

On Week 8, you'll be performing a technical AMRAP @ your TBT (250lbs). Put the number of reps performed into a 1RM calculator... This will be your new max.

INCREASING FREQUENCY

Increasing frequency is another good way to increase volume of the lift you're trying to improve. For example, if your squat needs work, I recommend increasing your frequency to up to 3 times a week. You can work at different rep ranges on each day, but keep the intensity low. The more quality reps you can perform and the more bad reps you avoid, the better. Using the same 315lb 1RM in the examples above, 1 week of training may look like this:

Day 1: 3x6 @ 235lbs (75%)

Day 3: 3x12 @ 190lbs (~60%)

Day 5: 4x3 @ 235lbs (~75%)

The philosophy

These are only examples, as there are other strategies that can be used here. However, the overarching philosophy of this method should be:

Consistently working with a sub-maximal weight that you are comfortable with.

Keeping intensity relatively the same (below your TBT) and progressive overloading by increasing reps or sets, NOT intensity (weight).

Spending plenty of time performing reps at the same intensity will make you more aware of technical changes and improvements from week to week.

Use this early on in your lifting career or ASAP if form breakdown is an issue for you.

Use this in the "off-season" and not as preparation for a powerlifting meet.

Please note that the set and rep schemes listed above are specific to the % of 1RM at which technique breaks down in the example I used.

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)