Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]

In part 2 of this article series, we’ll discuss principles and training methodologies that can be used to optimize combat sports training within-session and within the week.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

In part 2 (this part), we will discuss the specifics week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

Read PART 1 on Macrocyclic and Mesocyclic Training Here

the microcyclic layer

Programming on the microcyclic layer is concerned with optimizing training on the weekly level. Given the amount of sessions in a combat sports athletes’ schedule, we must consolidate them by avoiding any interference effects and create systems that can manage training stressors more consistently. Here are some guiding principles and strategies that you’ll find in my S&C programs.

High/low structure

I use a high/low structure to guide the initial parts of my program planning; a system popularized by track coach Charlie Francis to categorize running intensity and it’s affect on speed adaptations.

“High” training days consists of training modalities that require a large amount of neuromuscular-activation, a large energy expenditure and/or a high cognitive load - all stimuli that require a relatively longer period of full recovery (48-72 hours). Conversely, “low” training days are less neurally, bioenergetically and mentally demanding, requiring a relatively shorter period of full recovery (~24 hours).

Adapted to the world of combat sports, all training modalities, from sparring, technique work, heavy bag training to weight room sessions can all be categorized into high and low. This allows us to visualize the training and recovery demands of sessions throughout a full week of training.

Ideally, we would schedule training so that we alternate high and low training days so that the athlete is adequately rested for the most demanding sessions, but the reality of the fight game makes this challenging in practice. Some sessions, on paper, fall in between high and low categories in terms of physiological load. Regardless, using a high/low structure is a great start to help manage training stress within a week of training.

Condensed conjugate method

First of all, the conjugate method (CM), originally created for powerlifting performance by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell uses Max Effort (close to 1RM lifting), Dynamic Effort (low % of 1RM performed in high-velocity fashion and Repetition Effort (moderate % of 1RM performed for ~8-15 reps) all within a training week. The CM is based on a concurrent system (I discussed this in part 1, where training aims to develop several physical qualities within a shorter time frame - week and month).

The first time hearing of the condensed conjugate method (CMM) was from Phil Daru, S&C coach to several elite combat sport athletes out in Florida, USA who adapted the CM method to fit the tighter training schedule of fighters.

What is originally a 4-day split (CM) is condensed into 2 days (CMM). This is what the general structure/training split looks like within a week.

Day 1:

Lower Body Dynamic Effort

Upper Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Day 2:

Upper Body Dynamic Effort

Lower Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Max effort and dynamic effort training are both performed on the same day, however, to mitigate neuromuscular fatigue, they are rotated based on upper body and lower body lifts. If upper body compound lifts like heavy presses and rows are performed that day (max effort), bounds and jumps will be trained for the lower body to avoid excessive overload.

Similar to most concurrent-based training splits, a large benefit comes from the fact that movements are trained within the whole spectrum of the force-velocity curve (see figure below). Max effort training improves the body’s ability to create maximum amounts of force - grinding strength, while dynamic effort trains the body to be able to produce force at a faster rate - explosive strength/strength. Repetition effort is then used to target weak points and to create structural adaptations like muscle hypertrophy and joint robustness.

The CMM also shares some of the drawbacks of concurrent-based training set-ups. Single athletic qualities progress slower since multiple are being developed at the same time, however, this is only a minor issue considering the mixed demands of many combat sports. Certain modifications can be made to the template or perhaps block periodization can be utilized (see Part 1 of the article) if working with athletes that are clearly force-deficient or velocity-deficient (see the next section on velocity-split). Nonetheless, a pragmatic way to organize both high-velocity and slow-velocity exercises within a training week. I’ve had success implementing this type of training split in my combat sports S&C programs.

Velocity-split

Sticking with the theme of a concurrent-based system within the training week, another way to set up a microcycle is using a velocity-split. For example, in a 2-day training split, high-velocity exercises and low-velocity exercises would be trained separately.

Day 1:

Upper Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Lower Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Speed-Strength Exercises (Loaded throws, Olympic Lift deratives, Kettlebell swings, etc)

Day 2:

Upper Body Max Strength Lifts

Lower Body Max Strength Lifts

Repetition Effort Training (70-85% of 1RM)

Isolation Exercises

With concurrent training, we risk pulling an athlete’s physiology in opposite directions. This is avoided by grouping similar stressors together within each training day, throughout the week.

Additionally, this can be used to isolate high- or low-velocity training in order to target the weaknesses within an athlete’s force-velocity profile. Using the example split above, Day 2 would play a more important role in the training of a force-deficient athlete while Day 1 would be more effective for velocity-deficient athletes. We are still training both ends of the spectrum within a week but manipulate the training volume, and therefore emphasizing certain aspects of the training stimuli, to fit the needs of the athlete’s physical profile.

WITHIN-SESSION PROGRAMMING

When training multiple physical qualities within a workout, it is important to perform exercises in an order that optimizes training adaptations and reduces the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue. An effective training session will always start with a comprehensive warm-up routine, raising overall body temperature, warming up the muscles and joints, as well as “waking up” the nervous system so the athlete is ready for the work ahead. After that, we need a set of principles to guide how we will structure our training order.

principle of fatigability

Simply put, exercises that require higher neuromuscular output and physical readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue. These exercises are better performed at the beginning of a training session (after warm-ups) when the athlete is fresh and has all of their physical and mental resources. Max effort, max intent modalities like intensive plyometrics, high effort compound lifts and ballistics all fall under this category.

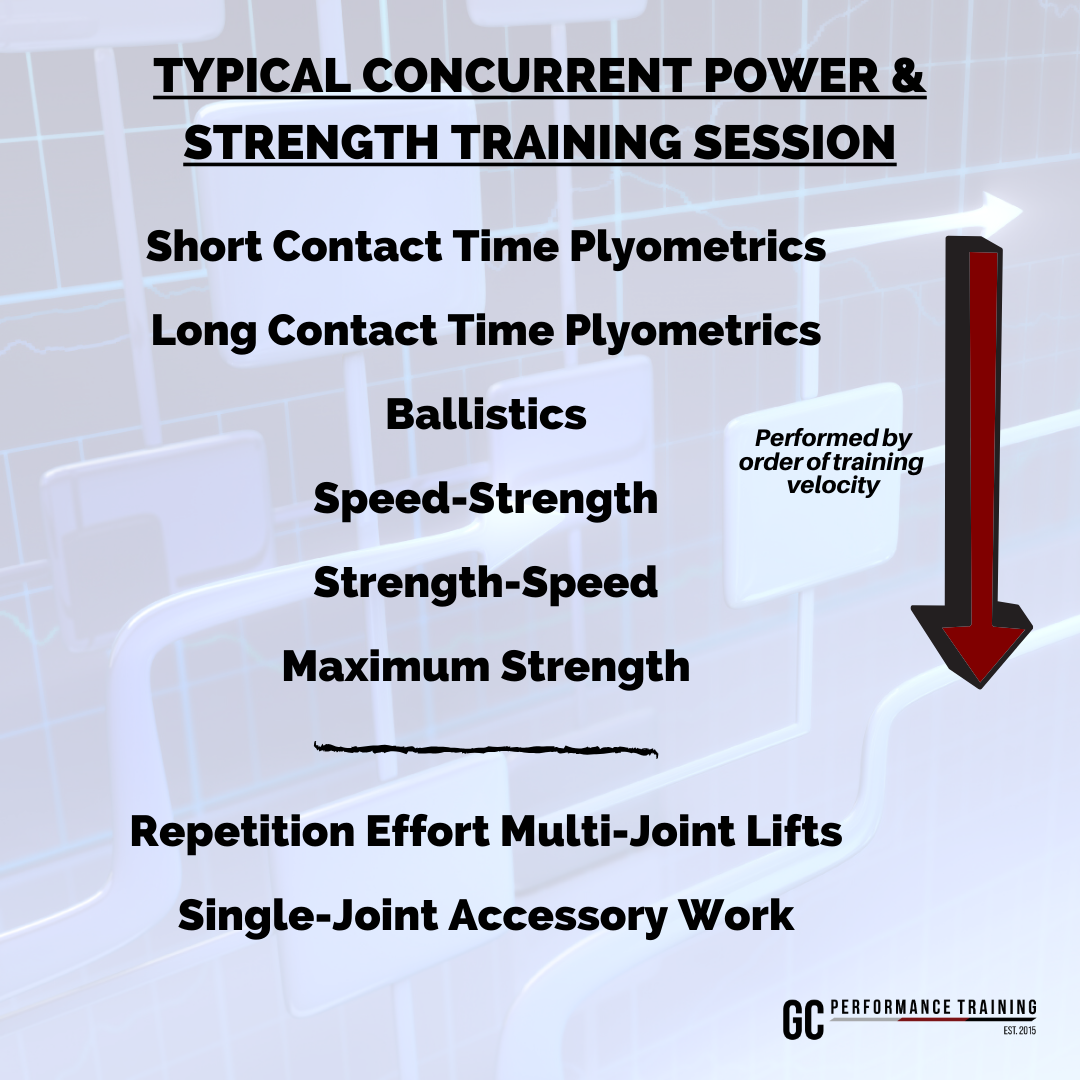

Contrastingly, exercises that require a lesser degree of neuromuscular output like accessory lifts, isolation lifts and stability training can be trained at the end of a session with little to no detrimental effects on training adaptations. If we use this principle to guide exercise order, this is what a typical concurrent power and strength training session might look like:

The same principle can be used if we were train both martial arts and S&C within the same day. Because of the importance of skills training, I would schedule it first. Pre-fatigue can be a tool to improve skill retention and transfer, but in most cases, only hampers skill acquisition and development by making it harder for combat athletes to participate in high quality, deliberate training.

PRIORITY

Prioritization is an exception to the principle of fatigability. An athlete should first perform exercises that are most important to their primary training goal (if they one that is clear-cut). Going back to our athlete is differing athletic profiles, a force-deficient athlete should focus on high-force producing exercises first thing in each training session in order to reap in the most training benefits. Likewise, a velocity-deficient athlete should perform high-velocity exercises before slower movements (the outcome is in line with the principle of fatigability but for different reasons).

Post-activation potentiation and contrast training

Post-activation-potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where rate of force development (RFD)/power is increased due to previous near-maximum neuromuscular excitations. This is another exception to the principles of priority and fatigability, whereby the athlete will deliberately perform heavy compound lifts first even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

I’ve written an article about this topic of within-session planning, covering these principles more in-depth. If you’d like to learn more, read “Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session”.

WRAPPING IT UP

Whenever I create an S&C program for combat sport athletes, I’m always considering all 4 layers of programming. Some of the specific methods I use like type of training-split or the type of volume/intensity undulating I use will change based on the athlete I’m working with, however, most of the governing philosophies (on the macrocyclic level - see Part 1) stay more or less the same.

It’s important for S&C coaches to adapt to information given in front of us, not be limited by scientific dogma, but at the same time, be willing to change and improve our philosophies over time. Since combat sports is a growing industry, so is S&C for combat sports. We must navigate through performance training with nuance.

The learning doesn’t stop there. Here are some combat sports S&C articles that will help you along the way.

Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high-performance combat sport athletes.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

This programming article series will be split into 2 parts.

In part 1 (this article), we will start with a low resolution view of training, in other words, the bigger picture. We will cover big concepts that guide our decisions when it comes to long-term athletic development and month to month training.

In part 2, we will work our way down to the specifics like week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

READ PART 2 ON MICROCYCLE AND WITHIN-SESSION PLANNING PROGRAMMING HERE

the MAcrocyclic layer

In training periodization, the macrocycle is the largest division of training periods, usually several months in length or even a years. When planning on the macrocyclic layer in combat sports, we are concerned with the long-term development of athletes. What the overall career trajectory looks like (considering factors like training and competition age) as well as overall athletic development/progression from fight to fight.

Below are some philosophies and frameworks I use to govern development on the macrocyclic level.

LTAD Model

The long-term athletic development model (LTAD) model is a framework created by Dr. Istvan Balyi to guide the participation, training and competitive aspects of sports and physical activity throughout different stages of development for any athlete.

No matter what stage an athlete comes into the sport, a base must be built for performance potential to flourish in the future. Whether your athletes’ goal is to compete in boxing, wrestling or Judo in the Olympics, or turn to a career in prize fighting for international organizations such as the UFC or One Championship, a coach must see S&C as a long-term investment. Coaches that partake in short-term thinking - disregarding joint health, brain health and overall athletic longevity do nothing but limit the potential of an athlete.

Skill Practice Rules All

The skill practice rules all paradigm acknowledges that skill is the most important aspect of combat sports, rather than physical ability. S&C coaches new to the combat sports world are hesitant on adopting this philosophy (the ones who do fail to manifest this in their programming) as many of them view high performance training through a purely physical and bioenergetic point of view - thinking that maximum strength, power and great endurance (as objectified through lab testing numbers) is what ultimately influences the outcome of a fight.

However, by undervaluing sport-specific skills such as pattern recognition, tactical strategies and fight experience, these coaches make mistakes in the training process that sacrifices skill development and expression for superficial strength and power gains.

Without getting into too much detail, I’ve used this skill practice rules all paradigm to influence my programming so that training stress is distributed more optimally throughout training camps and S&C plays a supplementary role, allowing skill expression to shine on the night of a fight.

If you’d like to learn exactly how I apply this into my S&C programs, I highly recommend you check out the eBook I mentioned earlier.

The Barbell Strategy

Originally a financial investment strategy, the barbell strategy adapted to S&C involves utilizing “low-risk” training methodologies as the main driver behind performance improvements; only prescribing special developmental exercises and “high-risk” exercises when the foundational bases have been thoroughly covered.

With the rise of social media and wild exercise variations promising transfer to the sport, it’s easy to get lost and major in the minors. Landmine punches and brutal conditioning circuits have a place in combat sports S&C but plays a very small role in driving meaningful improvements in fighters.

As a rule of thumb, 80-90% of time should be invested in “low-risk” exercises, and the rest 10-20% into more specialized training. However, don’t fall into the trap of thinking “low-risk” exercises are don’t drive any improvements in sports performance or that they are picked blindly, they should still be selected with the physical demands of the specific sport in mind. A comprehensive needs-analysis of the sport needs to be performed beforehand. Given the limited time I may have with a fighter (2-3 sessions a week), I must select exercises that have a favourable cost-to-benefit ratio.

Looking at the bigger picture, the barbell strategy keeps my programming and exercise selection process grounded by reminding me what improvements I can realistically make with combat fights as an S&C coach and what influence I have over the training process.

Agile Periodization

This is a term coined by S&C coach Mladen Jovanovic. As described by Mladen:

“Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistic approach to planning” (Jovanovic, 2018).

Agile periodization represents a training philosophy that’s based on the uncertainty of human performance and one that permeates multiple layers of my programming and planning.

Rigid periodization models that we S&C coaches learn from textbooks and university classes unfortunately have little success given the unpredictability of the real-world and the volatility of combat sports training schedules, competition dates and career trajectories. Furthermore, mindlessly following scientific dogma and abstractions give us a false sense of predictability and stability in the training/planning process.

While we still need to set objective long-term goals and have a vision of what success looks like for our high-performance athletes, the agile periodization framework encourages simultaneous bottoms-up planning: what does the next best step look like given the athletic and environmental constraints in front of us? Does the long term goal change with the new information we’re receiving about the athlete and their progress?

The mesocyclic layer

Mesocyclic planning is concerned with how training variables change from month to month - most of these strategies have fancy names and are ones you normally hear when reading about training periodization.

The overarching goal with mesocyclic planning is to create a training program that bests develops the athletic qualities a combat athlete needs in order to excel at their sport. Whether these qualities should be trained simultaneously, sequentially or in a specific order is what makes one periodization model different than the other.

Let’s explore a few options.

Block Periodization

Commonly confused with programs that simply have “blocks” or “phases” of training, block periodization (BP) is a specific periodization strategy popularized by soviet coaching figures like Verkoshanksy, Bondarchuk and Issurin (article here on a review on different types of training periodization). BP consists of distinct blocks of training aggressively targeting certain physical qualities, such as maximum strength, or plyometric ability (and doing the bare minimum to attempt to maintain other qualities). The basis behind BP is that elite-level athletes who are reaching the functional limits of their physical performance require highly concentrated training loads in order to further increase performance. This becomes problematic when translating it to the world of combat sports training. Here’s why:

Imagine a 4-week block dedicated to increasing maximum strength where the majority of your weight room training volume comes from heavy lifts above >85% of 1RM. The lack of a high-velocity stimulus combined with the fatigue incurred throughout this block will unquestionably hinder an athlete’s ability to develop new skills on the mats or clock in high-quality sparring sessions.

The physical demands of combat sports are not extreme (compared to pure-strength or pure-endurance sports), what’s important is improving key qualities slowly over time while still maintaining physical and mental energy to excel in the practice room - where it counts.

It’s a good idea to separate training into distinct blocks/phases with clear goals, However, implementation of BP, characterized by aggressive investments into single traits and heavily reliance on cumulative and residual training effects, is best left for sports like cycling and powerlifting.

Triphasic Training

Triphasic training, popularized by Cal Dietz, also shares some elements of block periodization, where each block heavily emphasizes the eccentric, isometric and concentric (3 phases - triphasic) muscle actions sequentially to improve speed and power at the end of the block.

Typically, a general preparation phase (GPP) is done prior to jumping into a 6-week triphasic training phase consisting of 2 weeks of eccentric focus, 2 weeks of isometric focus and 2 weeks of concentric focus. This is all capped off with a high velocity peaking/realization block lasting several weeks (depends on the athlete/sport/schedule).

Much like block periodization, triphasic training requires adequate preparation time before a fight or competition and can run into the same problems that BP does, of sacrificing quality of skills training in order to further build physical abilities.

Some coaches have made this work, notably William Wayland of Powering Through Performance, who adapted the triphasic model to MMA athletes, compressing the model and by utilizing supramaximal loading. William breaks it down much better than me so I suggest reading up on it here: “Applying The Compressed Triphasic Model with MMA Fighters”.

Concurrent Method

Like the name suggests, this method involves developing multiple physical qualities concurrently, from month to month. The emphasis on each quality is not implemented as aggressively as it would be in BP or a triphasic set up, so it allows for more programming flexibility - changing intensities and volumes where the S&C coach sees fit (see agile periodization).

By training concurrently, the training stimulus is spread amongst all physical qualities (endurance, strength, plyometric ability, power-endurance, etc) - no physical trait is being neglected, therefore an athlete’s physical readiness remains relatively stable from month to month. A potential downside to this method is that if we’re spreading the training volume thin amongst different traits, we risk watering down the training process and end up not making any tangible process in each area.

Contrastingly, this coincides with the concept of minimal-viable program (MVP) brought up by Mladen Jovanovic, a concept that states that a program that covers all areas will, over time, tell us what changes need to be made based on strengths, weaknesses and any data that comes out of that. Each subsequent training phase will then be modified to suit the needs of the athlete.

These paradigms and philosophies that occur on the macro- and mesocyclic level govern the way we view physical preparation for combat sport athletes, also affecting the decisions we make downstream. In part 2, we will go over strategies we can apply on the microcyclic level and within any given S&C session. (Click here to read part 2).

Squats vs. Trapbar Deadlift, Hypertrophy Training and Plyometrics - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #2

This week’s topics discuss the differences between squats and trapbar deadlifts in a training program, the use of a “hypertrophy phase” for combat athletes as well as how to introduce plyometrics in a fighter’s training.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is the difference between squats and trapbar deadlifts? They both have similar joint angles.

To the naked eye, they have similar joint angles - especially if you’re using the high handles of a trap bar, meaning you’re “sitting” much deeper into the deadlift. Even if this is the case, squats should have a much larger degree of knee flexion, stimulating more of the distal quadriceps and lower leg muscles.

In terms of programming, there are distinct scenarios where I would use one over the other.

The trapbar deadlift is one of the exercises in the weight room that allows an athlete to lift the most weight. Because of this, I use this to build systemic, full-body strength through high-intensity loads. Although the degree of knee flexion is larger than other variations like the conventional or Romanian deadlift, an emphasis is still being put on the muscles of the mid- and lower-back. Trapbar deadlifts play a big role in improving “pulling-strength” in my combat sport athletes.

In contrast, when I want to build more robust knees and lower-body “pushing-strength”, I prescribe squats. Front squats, safety bar squats, back squats, heels-elevated cyclist squats; any variation that I can load safely and effectively with my athletes and achieve the deep knee flexion angles we want to see in order to develop quad strength.

QUESTION #2 - How would you structure hypertrophy phase while doing MMA?

I wouldn’t. Muscle hypertrophy is rarely a training goal for combat athletes, unless they’re trying to move up a weight class and even then, that is better performed over the span of several months or years, not through a 8 or 12 week phase.

If you find yourself in that position, the best options are to slowly increase the training volume of compound lifts and increase caloric intake over time. The key here is a gradual increase over the span of several training cycles. This way, the muscle soreness from sharp increases in resistance training volume will not disrupt skills training. As well, this gives time for the athlete to become acclimated to their increasing bodyweight.

There are more benefits to a high volume training phase than just hypertrophy.

Increased muscle coordination via repetition volume

Re-sensitization to high-intensity training

Muscular endurance and work capacity

Pair this with proper fueling and let hypertrophy be a by-product.

Question #3 - How would you start with plyometrics for a fighter that’s never done plyometric training before?

For lower body plyometrics like jumps and hops, start with “extensive” plyometrics. Also known as low level plyometrics. Simple exercises like plyometric pogo hops can be prescribed to help the fighter familiarize themselves with redirecting energy/force before moving onto more intensive plyometrics like depth jumps and lateral bounding.

Because extensive/low-level plyometrics are lower impact, they can be trained with relatively high volumes which in turn, will develop favourable tendon and muscle properties that will aid in getting the most out of intensive plyometrics.

For the upper body, exercises like assisted plyometric push ups as well as continuous medicine ball slams are a good choice.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Training Session Structure, Single Leg Explosiveness and High/Low Training - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #1

This week’s questions and answers session covers topics such as training session structure, single leg training for power and explosiveness as well as high/low training categorization.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is your philosophy on the structuring of a training session?

The overarching goal behind structuring a training session is to optimize the training adaptations from each exercise within the given session.

First things first, any strength and conditioning training session for a combat sport athlete will start off with a warm-up. I utilize a “RAMP” warm up, the main goal is to raise body temperature, activate muscles, mobilize the joints and potentiate the athlete’s neuromuscular system system to reach the intensities seen in the training session.

The second order of training involves performing exercises that have require a high neuromuscular demand. These are usually high-velocity or high-force output exercises like plyometric jumps and medicine ball slams or heavy compound lifts. The reason why these are performed first is because these training modalities are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigued. In other words, athletes will not be able to reap in the benefits of plyometric and max-strength training if those exercises are placed near the end of the session.

Followed by this, are accessory exercises that are single-jointed or aimed at smaller muscle groups. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Conditioning, depending on the type, will usually be placed at the end of the session.

Here is an example of a full body MMA workout (performed descending order) following these training session structure principles:

RAMP Warm Up (Mobility flow, FRC, Core training, Bodyweight Jumps)

DB Weighted Plyometric Jump

Plyometric Push-Ups

Banded Zercher Squats

Barbell Overhead Press

Cossack Squats + Rotating Lower Back Extension Superset

Banded Rear Delt Flies + Bicep Curl Superset

Aerobic Power Intervals

Cooldown

There are some nuances to structuring a training session however, especially if you’re using methods like post-activation-potentiation or if you’re prioritizing certain power, strength or structural training qualities. I’ve written an in-depth article “Exercise Order - Principle for Sequencing A Training Session”. In this article, I also detail the principles of fatigability and prioritization to help you navigate training session programming. Check it out.

Question #2 - How do you develop single leg or staggered stance explosivity?

Single leg power is first built on a base of bilateral strength and unilateral stability. Before chasing power and explosivity in split or staggered stance movements, ensure that you have spent time building up your strength through squat, deadlift and split squat variations.

Moving forward, some of my favorite exercises for combat sport athletes include lateral bounding exercises, staggered stance kettlebell swings and staggered stance trapbar deadlifts (links included).

The reason I prefer these exercises is because of their ability to transfer over to both striking and grappling performance.

Lateral bounding variations develops lower body power in a way that compliments the in-and-out and angle changing agility demands of striking sports.

Staggered stance variations like kettlebell swings and trapbar deadlifts develops all of the strength and power qualities similar to it’s even-stance counterpart but puts extra emphasis on the back leg. By overloading the back foot and hip, it can possibly enhance force production in back-foot-driven grappling and striking movements such as shooting the double leg takedown or the power-straight and rear power-kick.

Question #3 - What happens if MMA workouts fall in between the high/low categorization of training you’re talking about in ebook?

Many training sessions or training days in reality will fall in between high and low. When this happens, I tend to side on the conservative side and count them as high.

The high/low categorization I mention in my ebook is simply a tool used to help us better understand and balance training stress throughout a training week. The important thing is to consider the training volume and intensity of each training session, the associated recovery cost, and how it will affect performance on subsequent training sessions or the next training day.

If you have a hunch a particular training session or class incurs much more stress than you originally thought, take some readiness data post-training and track fatigue markers like muscle soreness or nervous system readiness through jump or grip testing.

Remember, nothing in the chaotic world of combat sports training is set in stone. It’s great to have a framework to guide you, but this does not replace trial and error and constant refining of the training and planning process.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Alternatives to Olympic Weightlifting For Power Development

Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

This is a guest post written by Vancouver-based personal trainer and S&C coach Jason Lau of Performance Purpose. Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

Olympic Weightlifting for S&C

Olympic Weightlifting is a sport in which athletes attempt to lift a maximum weight overhead using the two competition lifts: Snatch and Clean & Jerk. These competition lifts and their derivatives: hang snatch/clean, push press, snatch/clean pulls, power clean/snatch/jerk, can often be seen programmed outside of the sport, in an athlete’s strength and conditioning program.

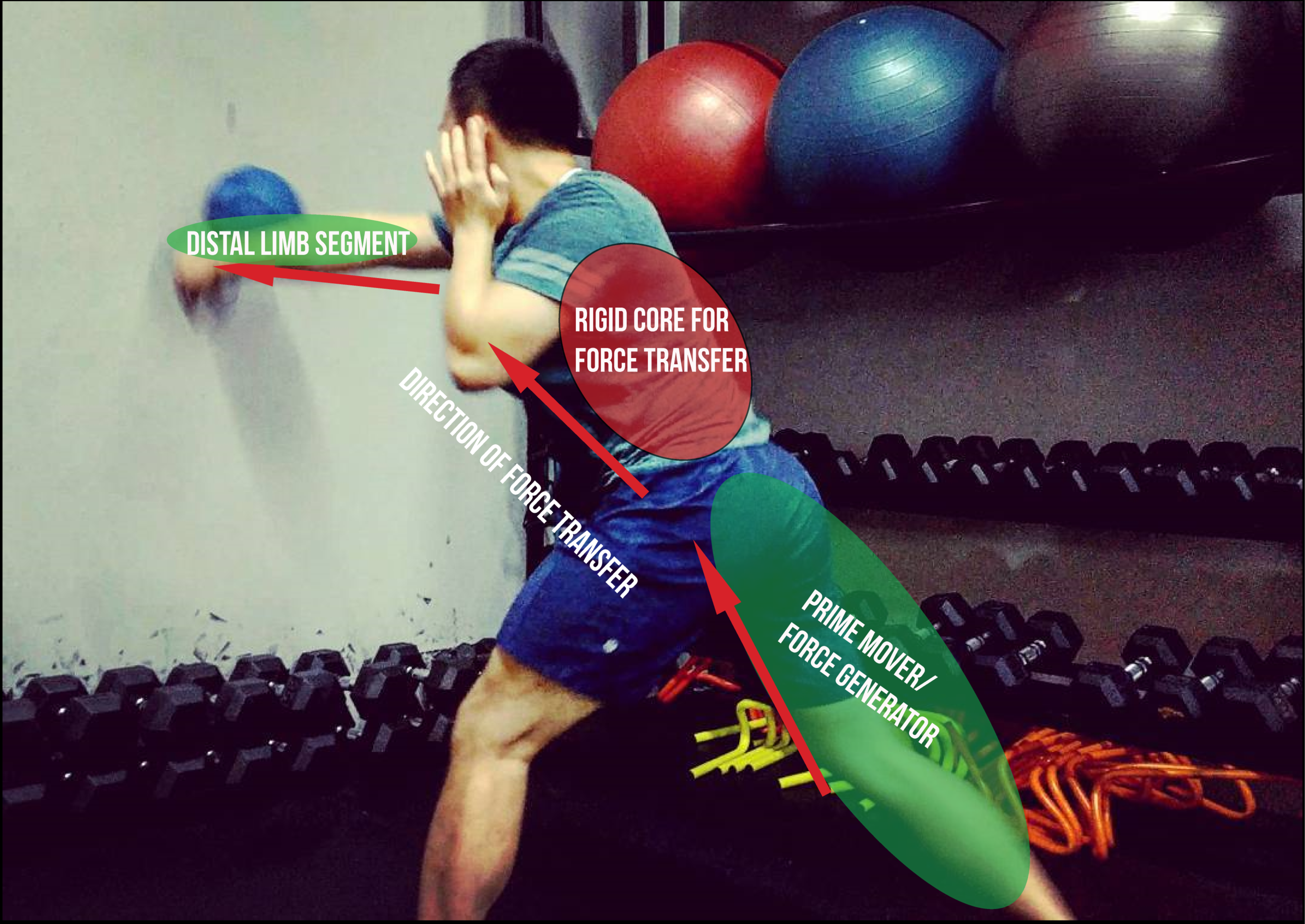

Due to the identical triple extension movement pattern (extension of ankles, knees and hips), seen commonly in weightlifting and sports, an athlete training the weightlifting movements can greatly improve the transfer of power from feet through torso to hands, as well as athletic coordination. In that sense, weightlifting can serve as a specific preparatory exercise that matches the high force and high velocity seen in sport that traditional heavy lifting cannot satisfy.

To quote Cal Dietz – “In order for an athlete to become fast, they must train fast.”

Then Why Use Alternatives?

Despite the power development that the weightlifting movements provides for athletes, there are also risks that you will have to consider as well.

Aside from aggravated joints such as knees, shoulders and hips, the lifts requires a high technical demand to perform correctly and safely. Time is required to master the technical aspect of the lifts. Time that should not be carelessly managed when an athlete is training for an upcoming game or season. Another factor to consider is the amount of training experience the athlete has in the weight-room. Mobility and injury restrictions may also interfere with the athlete’s ability in performing the lifts. Lack of ankle and overhead mobility and stability are restrictions are common and should be addressed before progressively overloading as it may lead to injury down the road.

Power development is also specific. In the world of S&C, specificity is king as game/competition date draws close. Does the athlete have to move heavy external or light loads within the sport? This will determine what type of loading scheme and stimulus is required. For example, a football linebacker will lean towards higher intensity hang cleans including prioritisation of strength due to the demands of their sport. On the other hand, the intensities a volleyball athlete’s program would see lighter intensities as external load is not needed to the same degree within the sport.

By taking into consideration of the limitations listed previously, alternatives can be performed and taught with relative ease while mimicking the classic lifts in velocity and movement pattern. Through alternatives, we can achieve the same stimulus that weightlifting movements bring while still improving strength in high-velocities.

Alternative Exercises

Trap Bar Jumps – Trap Bar Jumps is one of the go-to replacements for weightlifting. A previous study done by Timothy J. Suchomel indicates that when utilizing lighter loads (<40% of 1RM), the jumps displayed higher force output compared to a hang power clean at the same load. The learning curve of this exercise is relatively low where the majority of athletes can perform without difficulty while staying true to the natural movement pattern of jumping. With the versatility of the trap bar jump, it can be performed with a counter-movement while loaded with bands or weights.

Squat Jumps – Squat Jumps is a great transition towards power as an athlete is transferring out of their strength focused block. Aside from a smooth transition, a squat jump replicates the second pull during a clean. This can be performed from a quarter squat depth or full squat depth, all dependent on the athlete’s goals. Considering this exercise utilizes the squat movement pattern, it is different from an athlete’s natural jumping form so it may not satisfy the need of specificity.

Medicine Ball Toss – The med ball toss is a great exercise to have within one’s arsenal. Ballistics are predominantly concentric in nature allowing the athlete to focus on the acceleration phase without having to catch or decelerate at the end. The ability to reap the benefits of fast twitch muscle fibre contractions without the negative effects of eccentric forces can benefit the athlete. Tosses can be expressed throughout multiple planes of motion as well, not only vertically, that is what makes this movement so versatile.

Prowler Push – The vast majority of alternatives are bilateral in nature, but with Prowler Pushes and drags, we can achieve unilateral power with little technical demand on the athlete. This allows the athlete to drive off the ground and transfer force through the torso and into the prowler with no eccentric forces. This movement is versatile and can serve as a special developmental exercise for athletes in frequent sprinting sports.

To weightlift or not to weightlift?

That is the question. My answer? It depends.

I encourage coaches to look at the bigger picture. Does the athlete have enough time to learn the technicalities of the lifts? Are the athlete’s movement patterns proficient enough? Does the athlete have enough weight-room experience? Are there any severe mobility or stability issues that the athlete has to address beforehand? Are the alternatives sufficient for the time being? There is more than one route to achieve ideal athletic qualities. The factors that set apart good and bad S&C programs from each others are the risk to reward ratio, efficiency and specificity.

References

Suchomel, T. J., & Sole, C. J. (2017, September 1). Power-Time Curve Comparison between Weightlifting Derivatives. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5592293/

Shattock, K. (2018, February). The Use of Olympic Lifts and Their Derivatives to Enhance Athletic / Sporting Performance: A Mental Model. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322901416_The_Use_of_Olympic_Lifts_and_Their_Derivatives_to_Enhance_Athletic_Sporting_Performance_A_Mental_Model

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JASON LAU is a Strength & Conditioning / Physical Preparation coach and owner of PERFORMANCE PURPOSE based out of Richmond, BC. His passions include coaching and refining badminton, volleyball and hockey athletes, beginner to provincial level powerlifters, return-to-play rehab and general population clientele of all ages.

He aims to offer a systematic and evidence based approach to off-season and in-season training, translating the athlete’s weight room progress towards their specialized sport. His goal is to drive improvement and progress of each individual within the field of athletic performance.

Website: https://performancepurpose.ca/

Instagram: @performancepurpose

Optimizing The Warm-Up Using RAMP & Mobility Flows

The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

Its the general consensus that a warm-up is a mandatory component of any training session, no matter what sport or athlete you’re working with. The warm-up is also a component I’ve never stopped trying to refine over the years of coaching. I continuously ask myself: how do I help my athletes reach physiological and psychological readiness in the fastest, most efficient way possible?

As a result of poor practices in the past, as well as noticing trends in the high-performance world, I remain unconvinced on the concept of needing to perform an overabundance of exercises to “activate” muscles or “mobilize” the joints prior to training. Banded distractions, foam rolling, all the bullshit that people waste their time on because “that’s how everyone else does it in the industry”.

I was unsatisfied and baffled over the fact that a warm-up could potentially take up 25% of the time out of a training session. The warm-up is the low hanging fruit in terms of programming improvements. Simple changes to the warm-up protocol afford coaches and athletes more time to put into more meaningful training that develops athletic performance.

Out of a necessity to make my personal coaching sessions run in a more smooth and efficient manner, I’ve created a mobility flow warm-up as a way to address the first 3 letters of RAMP within one series of exercises.

A few principles I utilise follows the “RAMP” acronym.

(R)aise body temperature

(A)ctivate muscles

(M)obilize joints

(P)otentiate to reach intensities seen in the training program

In this mobility flow, I’ve sequenced multiple foundational movement patterns together such as squatting, hinging, lunges, pressing and rotating. Alongside the obvious rise in body temperature from performing this, the emphasis on large range of motion movements and anti-rotational positions addresses both the “activation” and “mobilization” aspects of a warm-up, saving time that can be put into actual, meaningful training.

While this mobility is ground-based and has a lot more potential for additional exercises, the principles I work with remain the same - achieve rise in body temperature, put muscles and joints through a large range of motion and improve proprioception as quick as possible. Modify this flow as you see it fits your training demands.

After the mobility flow, some sort of potentiating training follows in order to reach the intensities seen in the training session (whether the session is strength-based, plyometric-based or concurrent). More details about exercise order and potentiation can be found in my exercise order article.

Application

This mobility flow can be performed as a warm-up, as a cooldown, or as an active recovery protocol.

Warm Up: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Cooldown: 1-2 sets of 3-5 minutes

Active Recovery Protocol: Multiple sets of 3-5 minutes, or one long set of 15-30 minutes (Keeping HR in Training Zones 1 and 2)

Great response from my athletes so far. Will be refining this over the next few months. I hope you enjoy it.

[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports

My latest guest post on Fight Camp Conditioning covers the complexities of developing conditioning in the world of combat sports.

The training industry has come a long way since the time when tire flips and sledgehammer tire slams were the gold-standard for building endurance in MMA. As the sport becomes more popular and the quality of education for trainers improve, the way we approach conditioning should also improve. In the modern industry, it’s now about air-dyne assault bikes, mobility flows, perfectly crafted work-to-rest ratios and the use of heart rate tracking technology.

While there is nothing flawed with the current methods, I want to take a step back, revisit the components that make up conditioning performance in the world of combat sports and consider the application of these methods. My goal is to equip coaches, especially new coaches entering in the world of combat sports, with the knowledge needed to tackle the complexities that these combat sports possess.

Read More on the Fight Camp Conditioning Website

Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Given that you are able to select a handful of exercises that have a good chance of influencing strength & conditioning performance measures in athletes, you must be able to sequence each training session with the exercises in the “correct” order.

I say the word “correct” very cautiously as there are no absolute truths or right or wrong in the complex, unpredictable world of human performance. To navigate through the unpredictable nature of training, it pays off greatly to have a set of principles to prescribe and coach by, while still leaving room for flexibility when new information or new prioritizations arise.

Principles for sequencing a training session

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Fatigability

The principle of fatigability accounts for each exercise modality’s sensitivity to neuromuscular fatigue. Exercises that require high nervous system output and higher physiological and psychological readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue.

One explanation for this lie in the physiological characteristics of our muscle fibers. Fast-twitch, type 2 muscle fibers possess higher contractile speeds and a higher potential to produce contractile force. For this reason, they are favored during exercises that demand high-velocities and high-force outputs. Type 1 muscle fibers in contrast, are more resistant to fatigue due to their higher oxidative properties but as a consequence, have lower force-producing capabilities.

The larger velocity and force demands, the shorter they can be sustained for.

Following the principle of fatigability, exercises modalities like plyometrics, ballistic and maximum strength should then be performed first if they are to be trained concurrently within a training session.

Accessory exercises that are single-joint in nature, aimed at smaller muscles groups can be placed in the latter half of a training session. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Priority

The principle of priority is highly correlated to the principle of fatigue, and states that an athlete should be performing the exercises that are most important to their primary training goal, at a time when they have the most resources to do so. From an energetic and fatigue standpoint, this usually means the beginning of a training session when the athletes are at their highest point of psychological and physiological readiness (after a proper warm-up of course).

Not including the athletes at the ends of the endurance-strength spectrum (like endurance cyclists and powerlifters) the primary goal of many athletes is to develop higher rate of force development (RFD) / power and transfer this improved athleticism to sport-specific skills. Strength training is a secondary goal but must also be considered as it is crucial for second order effects such as injury risk reduction, slower-velocity force production and carryover to RFD training.

If your primary goal however, is to develop maximum strength, heavy compound lifts should come before high-velocity training. This sequencing does not follow the principle of fatigability, but satisfies the principle of prioritization.

the contrast training exception

Contrast training offers an exception to the principles of fatigability and priority, where heavy compound lifts are deliberately performed first to elicit a post-activation-potentiation (PAP) effect, even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where RDF/power is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. You’ve probably seen protocols utilized by strength & conditioning coaches such as heavy back squats paired with sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses paired with ballistic medicine ball throws and slams.

While the most common form of potentiating modality is maximum strength (85-100% of 1RM or <0.5m/s bar speed if you’re using VBT), I, along with other coaches I’ve communicated with, have had success using strength-speed exercises as a potentiating modality. Exercises like weighted trapbar jumps or Olympic weightlifting variations, loaded to achieve velocities around 0.75 - 1.0m/s.

Isolating Before Integrating in Rehabilitation & Return-To-Play settings

In the context of rehabilitation, priority is given to exercises that are aimed towards rebuilding the capacity of the injured muscle, joint, tendons and/or ligaments. In my return-to-play protocols for my athletes, I will place single-joint, stability and balance-based exercises in the beginning of the training session before integrating them back into strength and plyometric exercise regressions.

Since our main goal is rebuilding the athletes’ capacities, velocities and force-outputs are not expected to be high, therefore there will be little detrimental effects to placing those exercises last.

Anecdotally, my athlete’s have reported feeling more confident in performing strength and plyometric exercises after an extended warm up and emphasis on their injured area.

Wrapping it up

Exercise sequencing should be individualized on an athlete-by-athlete basis using the principles of fatigability and priority, while taking into account special circumstances like performing advanced training protocols or managing injured athletes. While some can argue exercise selection has a larger impact influencing performance outcomes and that exercise order is of less importance, using principles for exercise sequencing bring a consistent and strategic approach to the design and implementation of a training session that cannot be overlooked by high performance athletes and coaches.

Best Strength & Conditioning Books For The Thinking Coach

Almost monthly, I receive the question - “What books on strength & conditioning do you recommend?”. And every month I list out several books off the top of my head that I think ANY strength & conditioning coach can benefit from. But the reality is, the content you should be reading will be determined largely by your experience as a coach thus far in your career as well as the education you’ve received up until now.

Almost monthly, I receive the question - “What books on strength & conditioning do you recommend?”. And every month I list out several books off the top of my head that I think ANY strength & conditioning coach can benefit from. But the reality is, the content you should be reading will be determined largely by your experience as a coach thus far in your career as well as the education you’ve received up until now.

What good is it if a novice coach reads a science-heavy Soviet training textbook on subjects he is unable to fully grasp and put into practice?

Before you dive into the list below, I should start off by saying that this list is in no way exhaustive. These are only books I’ve came across over the last 6-7 years, I am sure there are way more. Some of these I’ve read from front to back, others - I’ve only read several chapters of. There is also nothing wrong with reading “past” your experience level as the categories below were created fairly loosely and only act as a guider.

[UPDATED JANUARY 2020] Here are my recommended readings based on experience level:

The Novice Coach

Anyone that has just entered the strength & conditioning field as a coach… all the way to coaches with 1-2 years of professional experience working with competitive athletes. Ideally already possessing basic knowledge of training program design, movement pattern coaching and general physical preparation.

Exercise Physiology 8th Edition - Nutrition, Energy and Human Performance by William McArdle

Periodization - Theory and Methodology of Training by Tudor Bompa, Carlo Buzzichelli

Practical Programming For Strength Training by Mark Rippetoe, Andy Baker

Olympic Weightlifting For Sports by Greg Evertt

Scientific Principles of Strength Training by Mike Israetel, Juggernaut Training Systems

Ultimate MMA Conditioning by Joel Jamieson

Training and Racing With A Power Meter by Huner Allen and Andrew Coggan

The Hybrid Athlete by Alex Viada

Conscious Coaching - The Art & Science Of Building Buy In by Brett Bartholomew

Optimal Nutrition For Injury Recovery by Lyle McDonald

Applied Nutrition for Mixed Sports by Lyle McDonald

the experienced coach

A strength & conditioning coach with 2+ years of experience coaching amateur competitive and/or professional athletes in multiple sports. This coach is familiar with the underlying mechanisms of exercise physiology and movement, understands how to manipulate training variables in a periodized plan and is ready to learn more training methods to further augment specific training adaptations.

Supertraining by Yuri Verkoshanksky, Mel Siff

Shock Method by Yuri Verkoshanksky

Science and Practice of Strength Training by Vladimir Zatsiorsky

Block Periodization - Breakthrough in Sport Training by Vladimir Issurin

Strength Training Manual - The Agile Periodization Approach Volumes One & Two by Mladen Jovanović

Triphasic Training: A Systematic Approach to Elite Speed and Explosive by Cal Dietz, Ben Peterson

The Governing Dynamics of Coaching - A Unified Theory of Sports Preparation by James Smith

Applied Principles of Optimal Power Development - Max Schmarzo, Matt Van Dyke

The Veteran coach

A highly read coach that also possesses extensive experience implementing the knowledge and methods learned from the previous section. These type of coaches are ready to further challenge their own training philosophies by reading work on psychology and philosophy in order to improve. Readings in this section teach us how to be more efficient thinkers and be more aware of our own logical fallacies and cognitive biases when it comes to planning, implementing and coaching in the field of strength & conditioning. These books can be read concurrently with any of the above.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb Collection - The Black Swan, Antifragile, Skin In The Game, The Bed of Proscrutes

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius

Economy of Truth: Practical Maxims and Reflections by Vizi Andrei

Got some suggestions? Comment down below, I would love to know which books have been positively impactful in your career as a coach.

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)

![[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1559464401554-UTSFUHZQUTNOISFNVX1P/Daryyl-Wong-Court.jpg)

![Tapering & Peaking: How To Design A Taper and Peak For Sports Performance [Part 2 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501283047888-1OMY4OC27GHE81P94CPG/mountains-sport-nature-human-mountain-climbing-wallpaper-hd-black-1920x1080.jpg)

![Overreaching and Overtraining [Part 1 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501052506104-FOT7NYG35KYOVLK3J12R/crossfit.jpg)