Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]

In part 2 of this article series, we’ll discuss principles and training methodologies that can be used to optimize combat sports training within-session and within the week.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

In part 2 (this part), we will discuss the specifics week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

Read PART 1 on Macrocyclic and Mesocyclic Training Here

the microcyclic layer

Programming on the microcyclic layer is concerned with optimizing training on the weekly level. Given the amount of sessions in a combat sports athletes’ schedule, we must consolidate them by avoiding any interference effects and create systems that can manage training stressors more consistently. Here are some guiding principles and strategies that you’ll find in my S&C programs.

High/low structure

I use a high/low structure to guide the initial parts of my program planning; a system popularized by track coach Charlie Francis to categorize running intensity and it’s affect on speed adaptations.

“High” training days consists of training modalities that require a large amount of neuromuscular-activation, a large energy expenditure and/or a high cognitive load - all stimuli that require a relatively longer period of full recovery (48-72 hours). Conversely, “low” training days are less neurally, bioenergetically and mentally demanding, requiring a relatively shorter period of full recovery (~24 hours).

Adapted to the world of combat sports, all training modalities, from sparring, technique work, heavy bag training to weight room sessions can all be categorized into high and low. This allows us to visualize the training and recovery demands of sessions throughout a full week of training.

Ideally, we would schedule training so that we alternate high and low training days so that the athlete is adequately rested for the most demanding sessions, but the reality of the fight game makes this challenging in practice. Some sessions, on paper, fall in between high and low categories in terms of physiological load. Regardless, using a high/low structure is a great start to help manage training stress within a week of training.

Condensed conjugate method

First of all, the conjugate method (CM), originally created for powerlifting performance by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell uses Max Effort (close to 1RM lifting), Dynamic Effort (low % of 1RM performed in high-velocity fashion and Repetition Effort (moderate % of 1RM performed for ~8-15 reps) all within a training week. The CM is based on a concurrent system (I discussed this in part 1, where training aims to develop several physical qualities within a shorter time frame - week and month).

The first time hearing of the condensed conjugate method (CMM) was from Phil Daru, S&C coach to several elite combat sport athletes out in Florida, USA who adapted the CM method to fit the tighter training schedule of fighters.

What is originally a 4-day split (CM) is condensed into 2 days (CMM). This is what the general structure/training split looks like within a week.

Day 1:

Lower Body Dynamic Effort

Upper Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Day 2:

Upper Body Dynamic Effort

Lower Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Max effort and dynamic effort training are both performed on the same day, however, to mitigate neuromuscular fatigue, they are rotated based on upper body and lower body lifts. If upper body compound lifts like heavy presses and rows are performed that day (max effort), bounds and jumps will be trained for the lower body to avoid excessive overload.

Similar to most concurrent-based training splits, a large benefit comes from the fact that movements are trained within the whole spectrum of the force-velocity curve (see figure below). Max effort training improves the body’s ability to create maximum amounts of force - grinding strength, while dynamic effort trains the body to be able to produce force at a faster rate - explosive strength/strength. Repetition effort is then used to target weak points and to create structural adaptations like muscle hypertrophy and joint robustness.

The CMM also shares some of the drawbacks of concurrent-based training set-ups. Single athletic qualities progress slower since multiple are being developed at the same time, however, this is only a minor issue considering the mixed demands of many combat sports. Certain modifications can be made to the template or perhaps block periodization can be utilized (see Part 1 of the article) if working with athletes that are clearly force-deficient or velocity-deficient (see the next section on velocity-split). Nonetheless, a pragmatic way to organize both high-velocity and slow-velocity exercises within a training week. I’ve had success implementing this type of training split in my combat sports S&C programs.

Velocity-split

Sticking with the theme of a concurrent-based system within the training week, another way to set up a microcycle is using a velocity-split. For example, in a 2-day training split, high-velocity exercises and low-velocity exercises would be trained separately.

Day 1:

Upper Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Lower Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Speed-Strength Exercises (Loaded throws, Olympic Lift deratives, Kettlebell swings, etc)

Day 2:

Upper Body Max Strength Lifts

Lower Body Max Strength Lifts

Repetition Effort Training (70-85% of 1RM)

Isolation Exercises

With concurrent training, we risk pulling an athlete’s physiology in opposite directions. This is avoided by grouping similar stressors together within each training day, throughout the week.

Additionally, this can be used to isolate high- or low-velocity training in order to target the weaknesses within an athlete’s force-velocity profile. Using the example split above, Day 2 would play a more important role in the training of a force-deficient athlete while Day 1 would be more effective for velocity-deficient athletes. We are still training both ends of the spectrum within a week but manipulate the training volume, and therefore emphasizing certain aspects of the training stimuli, to fit the needs of the athlete’s physical profile.

WITHIN-SESSION PROGRAMMING

When training multiple physical qualities within a workout, it is important to perform exercises in an order that optimizes training adaptations and reduces the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue. An effective training session will always start with a comprehensive warm-up routine, raising overall body temperature, warming up the muscles and joints, as well as “waking up” the nervous system so the athlete is ready for the work ahead. After that, we need a set of principles to guide how we will structure our training order.

principle of fatigability

Simply put, exercises that require higher neuromuscular output and physical readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue. These exercises are better performed at the beginning of a training session (after warm-ups) when the athlete is fresh and has all of their physical and mental resources. Max effort, max intent modalities like intensive plyometrics, high effort compound lifts and ballistics all fall under this category.

Contrastingly, exercises that require a lesser degree of neuromuscular output like accessory lifts, isolation lifts and stability training can be trained at the end of a session with little to no detrimental effects on training adaptations. If we use this principle to guide exercise order, this is what a typical concurrent power and strength training session might look like:

The same principle can be used if we were train both martial arts and S&C within the same day. Because of the importance of skills training, I would schedule it first. Pre-fatigue can be a tool to improve skill retention and transfer, but in most cases, only hampers skill acquisition and development by making it harder for combat athletes to participate in high quality, deliberate training.

PRIORITY

Prioritization is an exception to the principle of fatigability. An athlete should first perform exercises that are most important to their primary training goal (if they one that is clear-cut). Going back to our athlete is differing athletic profiles, a force-deficient athlete should focus on high-force producing exercises first thing in each training session in order to reap in the most training benefits. Likewise, a velocity-deficient athlete should perform high-velocity exercises before slower movements (the outcome is in line with the principle of fatigability but for different reasons).

Post-activation potentiation and contrast training

Post-activation-potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where rate of force development (RFD)/power is increased due to previous near-maximum neuromuscular excitations. This is another exception to the principles of priority and fatigability, whereby the athlete will deliberately perform heavy compound lifts first even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

I’ve written an article about this topic of within-session planning, covering these principles more in-depth. If you’d like to learn more, read “Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session”.

WRAPPING IT UP

Whenever I create an S&C program for combat sport athletes, I’m always considering all 4 layers of programming. Some of the specific methods I use like type of training-split or the type of volume/intensity undulating I use will change based on the athlete I’m working with, however, most of the governing philosophies (on the macrocyclic level - see Part 1) stay more or less the same.

It’s important for S&C coaches to adapt to information given in front of us, not be limited by scientific dogma, but at the same time, be willing to change and improve our philosophies over time. Since combat sports is a growing industry, so is S&C for combat sports. We must navigate through performance training with nuance.

The learning doesn’t stop there. Here are some combat sports S&C articles that will help you along the way.

Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high-performance combat sport athletes.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

This programming article series will be split into 2 parts.

In part 1 (this article), we will start with a low resolution view of training, in other words, the bigger picture. We will cover big concepts that guide our decisions when it comes to long-term athletic development and month to month training.

In part 2, we will work our way down to the specifics like week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

READ PART 2 ON MICROCYCLE AND WITHIN-SESSION PLANNING PROGRAMMING HERE

the MAcrocyclic layer

In training periodization, the macrocycle is the largest division of training periods, usually several months in length or even a years. When planning on the macrocyclic layer in combat sports, we are concerned with the long-term development of athletes. What the overall career trajectory looks like (considering factors like training and competition age) as well as overall athletic development/progression from fight to fight.

Below are some philosophies and frameworks I use to govern development on the macrocyclic level.

LTAD Model

The long-term athletic development model (LTAD) model is a framework created by Dr. Istvan Balyi to guide the participation, training and competitive aspects of sports and physical activity throughout different stages of development for any athlete.

No matter what stage an athlete comes into the sport, a base must be built for performance potential to flourish in the future. Whether your athletes’ goal is to compete in boxing, wrestling or Judo in the Olympics, or turn to a career in prize fighting for international organizations such as the UFC or One Championship, a coach must see S&C as a long-term investment. Coaches that partake in short-term thinking - disregarding joint health, brain health and overall athletic longevity do nothing but limit the potential of an athlete.

Skill Practice Rules All

The skill practice rules all paradigm acknowledges that skill is the most important aspect of combat sports, rather than physical ability. S&C coaches new to the combat sports world are hesitant on adopting this philosophy (the ones who do fail to manifest this in their programming) as many of them view high performance training through a purely physical and bioenergetic point of view - thinking that maximum strength, power and great endurance (as objectified through lab testing numbers) is what ultimately influences the outcome of a fight.

However, by undervaluing sport-specific skills such as pattern recognition, tactical strategies and fight experience, these coaches make mistakes in the training process that sacrifices skill development and expression for superficial strength and power gains.

Without getting into too much detail, I’ve used this skill practice rules all paradigm to influence my programming so that training stress is distributed more optimally throughout training camps and S&C plays a supplementary role, allowing skill expression to shine on the night of a fight.

If you’d like to learn exactly how I apply this into my S&C programs, I highly recommend you check out the eBook I mentioned earlier.

The Barbell Strategy

Originally a financial investment strategy, the barbell strategy adapted to S&C involves utilizing “low-risk” training methodologies as the main driver behind performance improvements; only prescribing special developmental exercises and “high-risk” exercises when the foundational bases have been thoroughly covered.

With the rise of social media and wild exercise variations promising transfer to the sport, it’s easy to get lost and major in the minors. Landmine punches and brutal conditioning circuits have a place in combat sports S&C but plays a very small role in driving meaningful improvements in fighters.

As a rule of thumb, 80-90% of time should be invested in “low-risk” exercises, and the rest 10-20% into more specialized training. However, don’t fall into the trap of thinking “low-risk” exercises are don’t drive any improvements in sports performance or that they are picked blindly, they should still be selected with the physical demands of the specific sport in mind. A comprehensive needs-analysis of the sport needs to be performed beforehand. Given the limited time I may have with a fighter (2-3 sessions a week), I must select exercises that have a favourable cost-to-benefit ratio.

Looking at the bigger picture, the barbell strategy keeps my programming and exercise selection process grounded by reminding me what improvements I can realistically make with combat fights as an S&C coach and what influence I have over the training process.

Agile Periodization

This is a term coined by S&C coach Mladen Jovanovic. As described by Mladen:

“Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistic approach to planning” (Jovanovic, 2018).

Agile periodization represents a training philosophy that’s based on the uncertainty of human performance and one that permeates multiple layers of my programming and planning.

Rigid periodization models that we S&C coaches learn from textbooks and university classes unfortunately have little success given the unpredictability of the real-world and the volatility of combat sports training schedules, competition dates and career trajectories. Furthermore, mindlessly following scientific dogma and abstractions give us a false sense of predictability and stability in the training/planning process.

While we still need to set objective long-term goals and have a vision of what success looks like for our high-performance athletes, the agile periodization framework encourages simultaneous bottoms-up planning: what does the next best step look like given the athletic and environmental constraints in front of us? Does the long term goal change with the new information we’re receiving about the athlete and their progress?

The mesocyclic layer

Mesocyclic planning is concerned with how training variables change from month to month - most of these strategies have fancy names and are ones you normally hear when reading about training periodization.

The overarching goal with mesocyclic planning is to create a training program that bests develops the athletic qualities a combat athlete needs in order to excel at their sport. Whether these qualities should be trained simultaneously, sequentially or in a specific order is what makes one periodization model different than the other.

Let’s explore a few options.

Block Periodization

Commonly confused with programs that simply have “blocks” or “phases” of training, block periodization (BP) is a specific periodization strategy popularized by soviet coaching figures like Verkoshanksy, Bondarchuk and Issurin (article here on a review on different types of training periodization). BP consists of distinct blocks of training aggressively targeting certain physical qualities, such as maximum strength, or plyometric ability (and doing the bare minimum to attempt to maintain other qualities). The basis behind BP is that elite-level athletes who are reaching the functional limits of their physical performance require highly concentrated training loads in order to further increase performance. This becomes problematic when translating it to the world of combat sports training. Here’s why:

Imagine a 4-week block dedicated to increasing maximum strength where the majority of your weight room training volume comes from heavy lifts above >85% of 1RM. The lack of a high-velocity stimulus combined with the fatigue incurred throughout this block will unquestionably hinder an athlete’s ability to develop new skills on the mats or clock in high-quality sparring sessions.

The physical demands of combat sports are not extreme (compared to pure-strength or pure-endurance sports), what’s important is improving key qualities slowly over time while still maintaining physical and mental energy to excel in the practice room - where it counts.

It’s a good idea to separate training into distinct blocks/phases with clear goals, However, implementation of BP, characterized by aggressive investments into single traits and heavily reliance on cumulative and residual training effects, is best left for sports like cycling and powerlifting.

Triphasic Training

Triphasic training, popularized by Cal Dietz, also shares some elements of block periodization, where each block heavily emphasizes the eccentric, isometric and concentric (3 phases - triphasic) muscle actions sequentially to improve speed and power at the end of the block.

Typically, a general preparation phase (GPP) is done prior to jumping into a 6-week triphasic training phase consisting of 2 weeks of eccentric focus, 2 weeks of isometric focus and 2 weeks of concentric focus. This is all capped off with a high velocity peaking/realization block lasting several weeks (depends on the athlete/sport/schedule).

Much like block periodization, triphasic training requires adequate preparation time before a fight or competition and can run into the same problems that BP does, of sacrificing quality of skills training in order to further build physical abilities.

Some coaches have made this work, notably William Wayland of Powering Through Performance, who adapted the triphasic model to MMA athletes, compressing the model and by utilizing supramaximal loading. William breaks it down much better than me so I suggest reading up on it here: “Applying The Compressed Triphasic Model with MMA Fighters”.

Concurrent Method

Like the name suggests, this method involves developing multiple physical qualities concurrently, from month to month. The emphasis on each quality is not implemented as aggressively as it would be in BP or a triphasic set up, so it allows for more programming flexibility - changing intensities and volumes where the S&C coach sees fit (see agile periodization).

By training concurrently, the training stimulus is spread amongst all physical qualities (endurance, strength, plyometric ability, power-endurance, etc) - no physical trait is being neglected, therefore an athlete’s physical readiness remains relatively stable from month to month. A potential downside to this method is that if we’re spreading the training volume thin amongst different traits, we risk watering down the training process and end up not making any tangible process in each area.

Contrastingly, this coincides with the concept of minimal-viable program (MVP) brought up by Mladen Jovanovic, a concept that states that a program that covers all areas will, over time, tell us what changes need to be made based on strengths, weaknesses and any data that comes out of that. Each subsequent training phase will then be modified to suit the needs of the athlete.

These paradigms and philosophies that occur on the macro- and mesocyclic level govern the way we view physical preparation for combat sport athletes, also affecting the decisions we make downstream. In part 2, we will go over strategies we can apply on the microcyclic level and within any given S&C session. (Click here to read part 2).

Squats vs. Trapbar Deadlift, Hypertrophy Training and Plyometrics - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #2

This week’s topics discuss the differences between squats and trapbar deadlifts in a training program, the use of a “hypertrophy phase” for combat athletes as well as how to introduce plyometrics in a fighter’s training.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is the difference between squats and trapbar deadlifts? They both have similar joint angles.

To the naked eye, they have similar joint angles - especially if you’re using the high handles of a trap bar, meaning you’re “sitting” much deeper into the deadlift. Even if this is the case, squats should have a much larger degree of knee flexion, stimulating more of the distal quadriceps and lower leg muscles.

In terms of programming, there are distinct scenarios where I would use one over the other.

The trapbar deadlift is one of the exercises in the weight room that allows an athlete to lift the most weight. Because of this, I use this to build systemic, full-body strength through high-intensity loads. Although the degree of knee flexion is larger than other variations like the conventional or Romanian deadlift, an emphasis is still being put on the muscles of the mid- and lower-back. Trapbar deadlifts play a big role in improving “pulling-strength” in my combat sport athletes.

In contrast, when I want to build more robust knees and lower-body “pushing-strength”, I prescribe squats. Front squats, safety bar squats, back squats, heels-elevated cyclist squats; any variation that I can load safely and effectively with my athletes and achieve the deep knee flexion angles we want to see in order to develop quad strength.

QUESTION #2 - How would you structure hypertrophy phase while doing MMA?

I wouldn’t. Muscle hypertrophy is rarely a training goal for combat athletes, unless they’re trying to move up a weight class and even then, that is better performed over the span of several months or years, not through a 8 or 12 week phase.

If you find yourself in that position, the best options are to slowly increase the training volume of compound lifts and increase caloric intake over time. The key here is a gradual increase over the span of several training cycles. This way, the muscle soreness from sharp increases in resistance training volume will not disrupt skills training. As well, this gives time for the athlete to become acclimated to their increasing bodyweight.

There are more benefits to a high volume training phase than just hypertrophy.

Increased muscle coordination via repetition volume

Re-sensitization to high-intensity training

Muscular endurance and work capacity

Pair this with proper fueling and let hypertrophy be a by-product.

Question #3 - How would you start with plyometrics for a fighter that’s never done plyometric training before?

For lower body plyometrics like jumps and hops, start with “extensive” plyometrics. Also known as low level plyometrics. Simple exercises like plyometric pogo hops can be prescribed to help the fighter familiarize themselves with redirecting energy/force before moving onto more intensive plyometrics like depth jumps and lateral bounding.

Because extensive/low-level plyometrics are lower impact, they can be trained with relatively high volumes which in turn, will develop favourable tendon and muscle properties that will aid in getting the most out of intensive plyometrics.

For the upper body, exercises like assisted plyometric push ups as well as continuous medicine ball slams are a good choice.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Training Session Structure, Single Leg Explosiveness and High/Low Training - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #1

This week’s questions and answers session covers topics such as training session structure, single leg training for power and explosiveness as well as high/low training categorization.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is your philosophy on the structuring of a training session?

The overarching goal behind structuring a training session is to optimize the training adaptations from each exercise within the given session.

First things first, any strength and conditioning training session for a combat sport athlete will start off with a warm-up. I utilize a “RAMP” warm up, the main goal is to raise body temperature, activate muscles, mobilize the joints and potentiate the athlete’s neuromuscular system system to reach the intensities seen in the training session.

The second order of training involves performing exercises that have require a high neuromuscular demand. These are usually high-velocity or high-force output exercises like plyometric jumps and medicine ball slams or heavy compound lifts. The reason why these are performed first is because these training modalities are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigued. In other words, athletes will not be able to reap in the benefits of plyometric and max-strength training if those exercises are placed near the end of the session.

Followed by this, are accessory exercises that are single-jointed or aimed at smaller muscle groups. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Conditioning, depending on the type, will usually be placed at the end of the session.

Here is an example of a full body MMA workout (performed descending order) following these training session structure principles:

RAMP Warm Up (Mobility flow, FRC, Core training, Bodyweight Jumps)

DB Weighted Plyometric Jump

Plyometric Push-Ups

Banded Zercher Squats

Barbell Overhead Press

Cossack Squats + Rotating Lower Back Extension Superset

Banded Rear Delt Flies + Bicep Curl Superset

Aerobic Power Intervals

Cooldown

There are some nuances to structuring a training session however, especially if you’re using methods like post-activation-potentiation or if you’re prioritizing certain power, strength or structural training qualities. I’ve written an in-depth article “Exercise Order - Principle for Sequencing A Training Session”. In this article, I also detail the principles of fatigability and prioritization to help you navigate training session programming. Check it out.

Question #2 - How do you develop single leg or staggered stance explosivity?

Single leg power is first built on a base of bilateral strength and unilateral stability. Before chasing power and explosivity in split or staggered stance movements, ensure that you have spent time building up your strength through squat, deadlift and split squat variations.

Moving forward, some of my favorite exercises for combat sport athletes include lateral bounding exercises, staggered stance kettlebell swings and staggered stance trapbar deadlifts (links included).

The reason I prefer these exercises is because of their ability to transfer over to both striking and grappling performance.

Lateral bounding variations develops lower body power in a way that compliments the in-and-out and angle changing agility demands of striking sports.

Staggered stance variations like kettlebell swings and trapbar deadlifts develops all of the strength and power qualities similar to it’s even-stance counterpart but puts extra emphasis on the back leg. By overloading the back foot and hip, it can possibly enhance force production in back-foot-driven grappling and striking movements such as shooting the double leg takedown or the power-straight and rear power-kick.

Question #3 - What happens if MMA workouts fall in between the high/low categorization of training you’re talking about in ebook?

Many training sessions or training days in reality will fall in between high and low. When this happens, I tend to side on the conservative side and count them as high.

The high/low categorization I mention in my ebook is simply a tool used to help us better understand and balance training stress throughout a training week. The important thing is to consider the training volume and intensity of each training session, the associated recovery cost, and how it will affect performance on subsequent training sessions or the next training day.

If you have a hunch a particular training session or class incurs much more stress than you originally thought, take some readiness data post-training and track fatigue markers like muscle soreness or nervous system readiness through jump or grip testing.

Remember, nothing in the chaotic world of combat sports training is set in stone. It’s great to have a framework to guide you, but this does not replace trial and error and constant refining of the training and planning process.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports

My latest guest post on Fight Camp Conditioning covers the complexities of developing conditioning in the world of combat sports.

The training industry has come a long way since the time when tire flips and sledgehammer tire slams were the gold-standard for building endurance in MMA. As the sport becomes more popular and the quality of education for trainers improve, the way we approach conditioning should also improve. In the modern industry, it’s now about air-dyne assault bikes, mobility flows, perfectly crafted work-to-rest ratios and the use of heart rate tracking technology.

While there is nothing flawed with the current methods, I want to take a step back, revisit the components that make up conditioning performance in the world of combat sports and consider the application of these methods. My goal is to equip coaches, especially new coaches entering in the world of combat sports, with the knowledge needed to tackle the complexities that these combat sports possess.

Read More on the Fight Camp Conditioning Website

MMA Strength & Conditioning - Experts ROUNDTABLE

With the pride, fame, and money that comes with prize-fighting, it's extremely important for strength and conditioning coaches to ensure the fighters are in top physical condition come fight night - the fighters' health depend on it.Strength and conditioning work must be balanced with martial arts skills training and psychological performance and therefore presents a complex problem for performance coaches to solve. Luckily there are professionals in the field to do just that - create strong and healthy athletes to elevate the sport of MMA.

Mixed martial arts (MMA) is one of the newest professional sports around and has been gaining a lot of popularity over the last two decades. With the pride, fame, and money that comes with prize-fighting, it's extremely important for strength and conditioning coaches to ensure the fighters are in top physical condition come fight night - the fighters' health depend on it.

Strength and conditioning work must be balanced with martial arts skills training and psychological performance and therefore presents a complex problem for performance coaches to solve. Luckily there are professionals in the field to do just that - create strong and healthy athletes to elevate the sport of MMA.

Before we start, I'd like to give a special thanks to all the coaches that spent time to contribute to this article. Thank you PJ, Phil, Carmen, Danny and Dr. Galpin. My goal was to reach out to coaches from different areas of expertise to compile a list of performance tips to help both the fitness and MMA community become more educated on the physical preparation process. Enjoy!

Geoff's Commentary: PJ Nestler will be starting this article off by dispelling the myths about strength training in the sport of MMA and how strength training can set the foundation for other physical attributes.

PJ Nestler

PJ Nestler is a performance specialist with a decade of experience training athletes from the UFC, NHL, NFL and MLB. With a passion for combat sports, he has worked extensively with multiple Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu World Champions like Otávio Souza and Ranked UFC fighters like Kailin Curran and Pat Cummins.

MMA Training Mistake: Lack of Strength Training

The myths behind strength training are endless. “Heavy lifting makes you tight”, “Lifting heavy weights makes you slow”, “too much muscle will make you gas out quicker” are some of the commonly perpetuated myths plaguing the combat sports community.

Since I could address each in their own full articles, for the sake of brevity I will just state that these claims are completely misguided, proven to be incorrect in hundreds of studies as well as decades of practical experience with coaches in the field improving athletic performance. Most are either completely fabricated (the tightness or gassing out myths), or are based on cherry picking research that is so esoteric to 99.99% of MMA fighters, just to sound contradictory or support unconventional and ineffective training methods, that all of this information only serves to further confuse the fighters who need it most.

The Solution

Strength is the underlying foundation upon which all other athletic abilities are built. Speed, balance, endurance, power, quickness, agility, coordination, all require specific levels of strength to reach a baseline performance as well as optimum levels. The word strength gets misconstrued with thoughts of 1 rep max squatting or deadlifting, and athletes typically don’t understand what true athletic based strength training looks like, and how much it can expand their physical abilities. Proper strength training will lead to improvements in all the above-mentioned motor qualities, aid in performance during strength based exchanges like grappling, improve operational outputs that will allow fighters to perform sport specific skills with greater power, speed, and duration, and will significantly reduce the incidence of injuries sustained in training.

Progressive overload of foundational movement patterns is one of the simplest, most well researched and practiced methods for improving athletic performance in existence. That is why it has been used at the highest level of sport for decades. This does not mean strength is the only important factor, and meathead coaches who love to crush athletes under the barbell are only fueling the fire from disbelieving fighters and skill coaches. There are many other necessary components of a well-structured performance training program, but proper strength training will always be the foundation that will keep fighters healthy, their bodies performing properly, and builds the motor qualities that will maximize their athletic potential.

Geoff's Commentary: Expanding on PJ's thoughts, Phil Daru details the why's and how's of strength training, specifically how to set up a strength training block to optimize performance and reduce injury rates.

Phil Daru (ACE, FMS, CFSC)

Phil "Bam Bam" Daru is a former professional MMA fighter and has competed in Strongman, bodybuilding and powerlifting. Holding an Exercise Science and Sports Medicine degree, he is now the Director of Sport Performance at American Top Team. Phil has worked with the likes of Joanna Jedrzejczyk, Tyron Woodley, Amanda Nunes, King Mo Lawal, Dustin Poirier and many more combat athletes.

The Why's and How's of Strength Development

Let me start off by stating that with any program there must be structured plan, a method and system that will facilitate growth. Without a plan, yes you plan to fail. So before we talk about strength in MMA we must make sure all keys to victory are set up to be worked accordingly to induce the greatest amount of success possible. Working on your technical skill is very important. These are the specific techniques and tactical drills that a fighter must show competence in to become a good fighter. Working on all aspects of the sport is the priority, you must create a hierarchy of modalities that you will need to put into place for maximum performance. Once this is in place and your drilling and technical practice has been set then we must get STRONG.

Strength first and foremost cannot be achieved without properly assessing movement capabilities of a fighter. If they have dysfunction, we must take care of the issue first before even thinking about putting external load on the body. Once all joints are mobile and stable in their given areas that's when the fun starts. When working with a fighter I must identify their weaknesses and strengths. What's their style of fighting, and what is their training background. When this is established, I find out when the competition is, then put together a solid strength training program to initiate progress.

The Structure of Strength Training

Depending on how long I have, I will start the camp with a structured block of hypertrophy and joint integrity training phase. This will include slow eccentric movement exercises and higher volume sets. Eccentric strength and plyometric exercises are used to prime their joints for high impact collisions that they will be experiencing in skills training (sparring, grappling). After a few weeks of that, we then go onto a strength block phase where we are trying to push the envelope of maximal strength output. Working primarily in the 85-90% of 1 rep max range with sets of 3-5 repetitions. All exercises will focus on 5 major movement qualities, a squat, hip hinge, push, pull, a carry, and core work. With these exercises, we cover all aspects of physical preparation with a general to specific periodization model.

In the beginning of the strength phase, we are working more on overall work capacity and movement efficiency. At the end of the strength phase, the focus becomes more specific to the sport. So exercises we choose will have a higher carryover to the physiological demands of the sport. For instance a Zercher Squat, Med Ball Double Under Carry, & DB Hip Bridge Floor Press will carry over well into the competition from a physical preparation standpoint.

A solid strength program should have two objectives in mind, get the athlete physically capable to train at a high level, and develop superior biomechanical and physiological capabilities over the opponent. Stick to basic multi joint movements at first like Back/Front Squat, Barbell Deadlift, Overhead Press, Sled Push/Pull, and Planks. Once the foundation of strength optimally met then we can move on to the specificity of sport exercises. Don't get caught up in trying to do what you see on social media do what needs to be done to help that athlete become better. Solid multi-joint movement exercises with stabilization techniques will get a fighter strong and capable to withstand load and impact.

We all should strive to become a stronger version of ourselves. Strength is not easy to develop but if all things are lined up and programmed properly then it can most definitely be done. Dominate your opponent and reduce injury while getting STRONG!

Geoffrey Chiu (BKin, NSCA-CSCS)

I don't have the same experience in the trenches in comparison to these coaches I look up to, however, I still have a undying passion for MMA and the field of strength & conditioning. My goal is to get people thinking more critically about training, periodization, nutrition, and at the end of the day, make a positive impact in the sport.

Visit me on my Facebook page and Instagram page where I post training footage, tips and weekly Q&As.

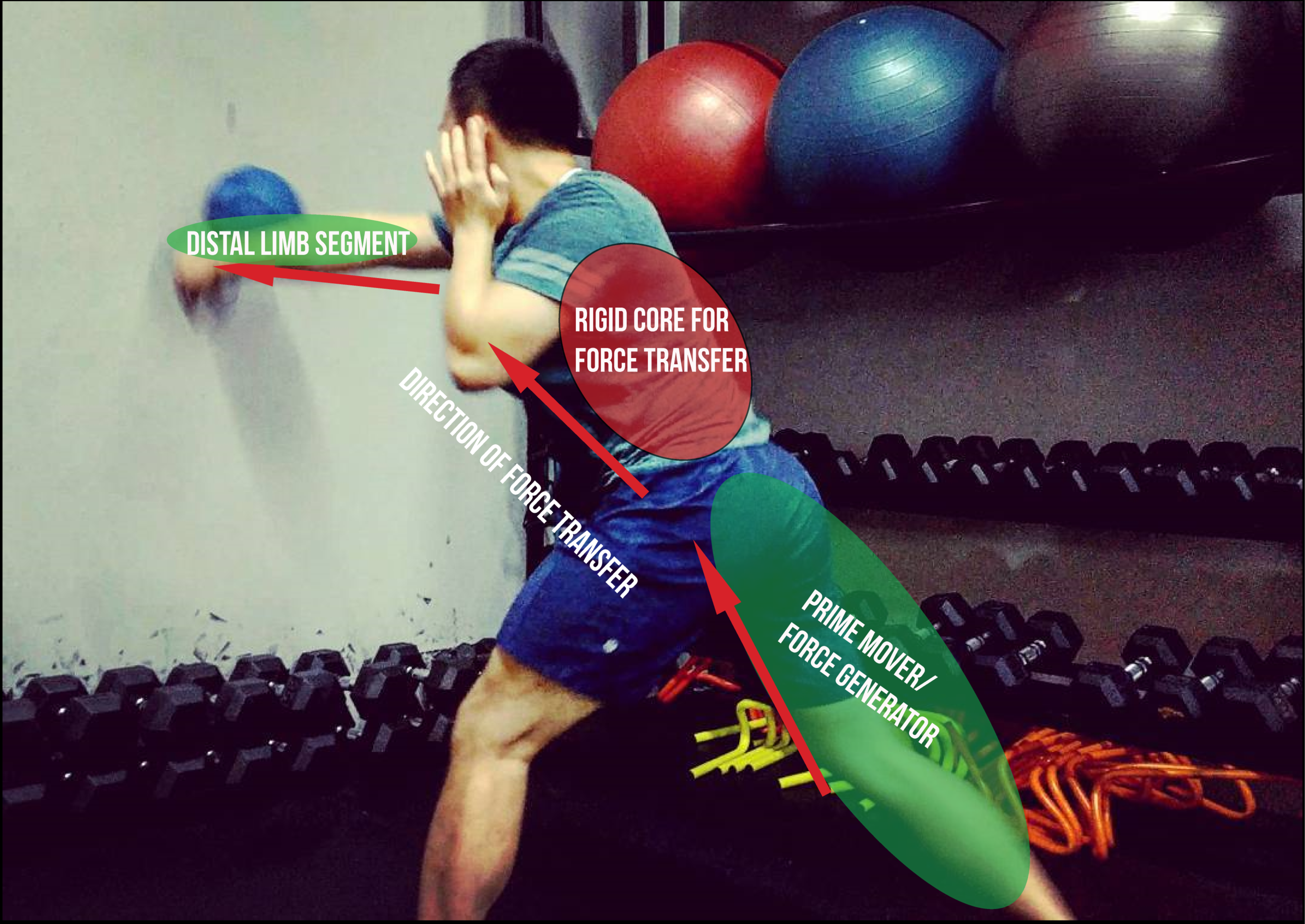

Thoughtful Exercise Selection

Building on Phil's knowledge on training structure and exercise selection, I wanted to talk about a mistake some coaches make: selecting overly-specific exercises in hopes of directly improving punching and kicking power, takedown strength, etc. Any MMA coach will tell you striking and grappling proficiency is built on the mitts or on the mats, not in the weight room.

As performance coaches, especially those who may have limited experience in the martial arts, we will do our athletes a disservice by trying to mimic and inappropriately load sport-specific movements in the weight room. Incorrectly holding a dumbbell while punching, or performing band-resisted kicks can alter the biomechanics of the movement, rendering any transfer effect to sport-specific performance obsolete. Banded punches and kicks if used, must be light enough where the quality of technique is retained but at the same time, be challenging for the athlete.

I'm also big believer that physical preparation should be injury-reductive in nature, while exercise selection aimed to improve strength, power or plyometric ability are individually catered towards the athletic profile of the MMA fighter. Are they primarily a striker, if so, what type of striking style do they use? Do they excel mainly as a powerful grappler, or an enduring, grinding wrestler? Do they have any hand, shoulder or hip injuries/limitations that may compromise exercise selection? These are all questions that should be asked when choosing exercises in a periodized plan. While the goal should be to improve their performance measures in the gym, it should not be done so at the expense of their sport-specific training.

In addition to a proper warm up like band pull-aparts for the shoulders or banded lateral shuffles for the hip, include injury-reductive exercises like decceleration drills and various concentric-focused or eccentric-focused plyometrics that improve the athlete's ability to absorb force and to increase knee and ankle resilience.

Instead of weighted punches/kicks, prescribe Olympic lifting variations, multiplanar medicine ball exercises, and exercises that improve core stiffness for better power transfer.

Instead of randomly timed tire flip circuits, box jumps and battle rope drills, utilize Zercher squats, foot-strength-focused plyometric drills and striking pad work intervals that reflect the energy systems used in a fight.

Geoff's Commentary: Many mentally tough athletes like MMA fighters feel uneasy about taking breaks and have a "no pain - no gain" mentality. However, it can't be stressed how important recovery is. Recovery times between sets and between training sessions have a significant impact on the adaptations that are being made as well as the mental and physical health of an athlete. Carmen Bott gives us information about the time periods of each recovery process.

CARMEN BOTT (MSc., BHK, CSCS)

Carmen Bott is an internationally renowned sport scientist and performance coach. She has been in the fitness training industry for over 20 years, focusing on strength coaching for combative and collision sport athletes.

She has recently put out an E-Book titled "The Wrestler's Edge: Complete Strength & Conditioning Program For Wrestlers". A complete strength & conditioning plan for some of the toughest athletes on earth.

The Details of Recovery Time

Encourage hard days followed by easy days, balanced nutrition following hard sparring and long rest periods between speed work if the goal is, in fact, to improve speed/alactic power.

The aim of this information is to give you knowledge about how long it takes to restore the body to a baseline state again.

When we look at recovery from a metabolic system standpoint, we are looking at specifically replenishing energy stores and recycling lactate back to stored fuel.

Geoff's Commentary: What is the adaptation we are seeking to make with the athlete? Are we trying to improve aerobic and anaerobic capacity? - Side with shorter, submaximal recovery times between sets.

Are we trying to improve speed and top end power output? - Utilize longer, maximal recovery times ensure peak power output is maintained from set to set.

Build in easy mobility and recovery days following hard sparring sessions and pay extra attention to recovery as the fight nears.

Geoff's Commentary: Weight cutting not only affects a fighter's performance, but puts their brain and bodily health on the line. Thus, preaching safe and effective weight cutting methods is both a personal and professional responsibility of a coach or nutritionist. Danny Lennon outlines a relatively uncommon, but safe way for athletes to cut weight for a fight.

Danny Lennon (MsC. NUTRI. SCI.)

Danny Lennon is a performance nutritionist to professional MMA fighters, boxers and competitive powerlifters. He is also the founder of Sigma Nutrition and the host of the Sigma Nutrition Podcast where he interviews top experts around the world to discuss everything fitness, training and nutrition related.

Cutting Fiber To Make Weight

There are several practices that can be used in a successful weight cutting strategy. Some of these are common knowledge amongst combat sport athletes (e.g. water restriction and induced sweating). However, there are a couple of excellent methods of achieving acute weight loss, without the potential for performance decreases, that I believe many athletes are unaware of.

One of these is the use of a short-term low-residue diet. This is something I use with every one of my athletes who are making weight. Quite simply, when we eat certain foods, particularly those high in fiber, a certain amount remains undigested in the intestine and hangs around for a few days. This "residue" of course has weight. So if we can reduce how much is contained in our intestine at a particular time, we can acutely drop bodyweight.

The use of a low-residue or low-fibre diet, is common practice in medicine when a patient is preparing for a colonoscopy or even as a treatment for IBS. This simply is the reduction of fibre into the diet to very low levels. So out go wholegrain products, vegetables, and high-fibre fruits. In the scientific literature we see a bodyweight drop of anywhere between 1 - 2%, even after only a few days of a low-residue diet, depending on the person's habitual fibre intake.

So combat sport athletes can drop 1% of BW reliably through this practice. And in contrast to dehydration and glycogen depletion, there is zero risk of a negative impact on performance. Of course, water loss and glycogen loss are still used in my Sigma Weight Cutting protocol, but through use of smart tactics like low residue dieting, we can decrease the amount of the weight cut that has to come via water loss. Therefore making it a bit more bearable, but more importantly, decreasing the risk of poor performance on fight night.

Geoff's Commentary: While the overuse of technology has not hit the sport of MMA by storm yet, it's nice to always remind ourselves that technology is a simply a tool in the toolbox, never a magic bullet. The best cryotherapy machine is only as good as it's context of use, the best high-altitude training chambers is only as good as the details of a periodized energy system development plan. Dr. Andy Galpin will expand on the use of technology in sports, and give a more detailed example.

dr. Andy Galpin (phd, cscs*d, nsca-cpt*d)

Dr. Andy Galpin is a professor at the Center of Sport Performance at CSU Fullerton and is the director of the Biochemistry and Molecular Exercise Physiology Lab. He has worked and consulted some of the best combat sport athletes in the world, from Olympic gold medalist freestyle wrestler Helen Maroulis to Top UFC featherweight Dennis Bermudez, as well as various MMA athletes.

Check out the Dr. Galpin and his co-authors Brian Mackenzie and Phil White's latest book titled "Unplugged: Evolve from Technology to Upgrade Your Fitness, Performance & Consiousness".

Use Technology to Cue, Calibrate and Create Independent Problem Solving

The latest generation of fitness trackers promise to be an all-in-one solution, offering everything from accelerometers that monitor our movement to altimeters that measure our altitude gains to blood oxygen sensors that supposedly help us identify sleep apnea. Yet in reality there is no tech-based magic bullet, no matter what marketers and publicists might want us to believe.

Instead of buying into such lofty claims, we should follow the advice that Tim Ferris gave me and my co-authors Brian Mackenzie and Phil White in our new book Unplugged: “Use the least technology necessary, not the most you think you can handle.” What Tim is suggesting is not that we should gather our devices, build a bonfire and ritualistically burn them before retreating into the woods. Rather, his point is that we should use technology purposefully, intentionally and with restraint to solve a specific problem, increase insight and connect the dots between what we’re feeling, what’s going on with our physiology and our performance outcomes.

One way to do this is for a coach to utilize tech appropriately as part of their teaching process with an athlete. The first step is to identify the problem and its effects. So let’s say an athlete is landing on their heels when they jump and run and as a result they’re making mechanical errors that compromise speed and power and could lead to injury. One way to use a simple piece of technology here would be to deploy the Shoe Cue, which is a piece of plastic with little knobs on the top that such an athlete could easily place into the heels of their shoes at the start of a training session.

When they jump or run and land on their heels, they’ll get immediate and somewhat painful feedback. You could then remind them to instead land on the balls of their feet and lightly tap their heels to the ground. This could be repeated through several running and jump rope drills, after which you’d ask the athlete to remove the Shoe Cue inserts. You’d then repeat the drills and hopefully they would’ve stopped landing on their heels and instead started landing softly on the forefoot area. Now they can use their newly attuned self-awareness for the rest of the session. As the coach, you could repeat this sequence – first using the Shoe Cue to highlight or exaggerate the heel-striking issue and encourage a certain solution, then removing the technology and having the athlete use their elevated instincts to improve the movement pattern.

This is just one simple example of how you can use fitness tech to overcome a specific issue as a cueing and re-calibrating tool that leads to improved and more self-reliant problem solving, not as the crutch that it can sometimes become. For more examples, check out Unplugged on Amazon. If you have questions, suggestions or comments, I’d also welcome the chance to continue the conversation on Instagram (@drandygalpin) or Twitter (@DrAndyGalpin). And yeah, I get the irony of a tech-aided discussion!

Geoff Commentary: In MMA, technology can be as simple as a tennis ball under the chin to remind fighters to keep their chin tucked, to complex devices like the Hykso punch intensity and velocity trackers. With so many skills, movement patterns, different training sessions and nutrition to balance, MMA fighters are already swarmed with information. As coaches, it is our job to ensure only the necessary pieces of technology are used - avoid the fluff and focus on principles and consistency.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Learning More About MMA Sports Science - Podcasts and Resources

You understand striking, you understand grappling, you understand the consequences and the excitement of MMA. Nothing better to round off your knowledge than understanding fight preparation and physical performance science. Here are some of my favorite podcasts and resources on MMA physical preparation.

In a "what have you done for me lately" sport, injuries and botched performances can make or break a fighter's career. From Cain's atrocious 200lb kettlebell swings, to Tony Ferguson's back-breaking deadlifts, bad training methods and protocols are everywhere. Luckily, there are great coaches and trainers that are changing the way fighters prepare and perform.

As a coach that aspires to train elite MMA athletes, I love learning about what goes into the preparation of elite MMA athletes and how it stacks up with my own training philosphies.

You understand striking, you understand grappling, you understand the consequences and the excitement of MMA. Nothing better to round off your knowledge than understanding fight preparation and physical performance science. Regular and hardcore fans alike will find these conversations interesting and can even be an eye opener for some. If you love sports science and if you love MMA, these are for you. Below are my favorite podcasts interviewing the top names in the world of MMA.

PJ Nestler (Preparation coach for BJJ champions)

http://sigmanutrition.com/episode173/

Corey Peacock (Preparation coach for Rumble, Suga, Mitrione, Michael Chandler)

http://sigmanutrition.com/episode171/

Danny Lennon's Performance Nutrition For Fighters - Common Mistakes:

http://sigmanutrition.com/episode141/

Dr. Doug Kalman (Performance nutritionist for former Blackzillians)

http://sigmanutrition.com/episode70/

Joel Jamieson (Strength & Conditioning coach to Mighty Mouse)

http://robertsontrainingsystems.com/blog/physical-preparation-with-joel-jamieson/

Loren Landow (Preparation coach for TJ Dillasnake)

https://fightcampconditioning.com/mma-strength-coach-loren-landow/

Chad Macias (Preparation coach for Phil Davis, Gastelum and others at Alliance MMA)

https://fightcampconditioning.com/podcast/chad-macias/

Phil Daru (Preparation coach at American Top Team)

http://www.mmafighting.com/2017/3/19/14841080/technique-talk-phil-daru-injury-training-performance-mma-news

Brett Bartholomew (Coach for many fighters at Unbreakable Performance - Rockhold, Faber, Ferguson, etc)

https://fightcampconditioning.com/podcast/brett-bartholomew-unbreakable-performance/

Jon Chaimberg (S&C Coach for GSP)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GYE5tfPY2GU

If you follow my blog, you'll know I've also written some of my own articles on MMA Strength & Conditioning: Part 1, Part 2. (I'm not sure when I'll get to "finish" off the series).

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)