[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball

In the world of performance training, a needs analysis of the sport is mandatory—but this only represents the first step to a fully optimized training program. Not all athletes of the same position will have the same playing style, and understanding this is important for designing and coaching a training program to optimize performance and injury mitigation.

In the world of performance training, a needs analysis of the sport is mandatory—but this only represents the first step to a fully optimized training program. A coach must also look at the playing style of the individual athlete and the demands the athlete puts on their body to be successful on the court. Not all athletes of the same position will have the same playing style, and understanding this is important for designing and coaching a training program to optimize performance and injury mitigation.

This article features a case study on Darryl Wong to show the inner workings of a performance training program for a basketball athlete.

READ MORE @ SIMPLIFASTER [CLICK HERE FOR THE ARTICLE LINK]

[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Plyometric Push-Ups and Progressions for Power Development

Push-ups are one of the most commonly used exercises among fitness buffs and elite-level athletes. As a closed-chained exercise that targets the chest and upper body musculature, push-ups are highly effective for improving upper body pushing strength and endurance, and can be done with no equipment.

Push-ups are one of the most commonly used exercises among fitness buffs and elite-level athletes. As a closed-chained exercise that targets the chest and upper body musculature, push-ups are highly effective for improving upper body pushing strength and endurance, and can be done with no equipment. There are plenty of regressions, progressions, and variations to pick from, making push-ups useful for athletes of all types. From bodyweight push-ups to loaded isometric push-ups, there are also various ways to load and challenge the movement...

[Read More @ SimpliFaster.com - Click Here For The Link]

The Science of Core Training: Training Methods & Application (Part 2 of Core Training Series)

Part 2 of this core stiffness article series will cover the core training principles and methods that drive short and long-term improvements in performance.

Read Part 1 Here

In part 1, I went over what the core is and the function of core stiffness in relation to sporting performance and optimal force and power output. To recap: core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed.

Highly recommend reading part 1 before continuing on with this article.

In part 1, I mentioned that improving performance via increased core stiffness will depend on multiple variables:

The nature of the sport and the energy systems involved (How long is the core braced for? Does the athlete need more strength? Or more endurance?)

The particular movement you're trying to improve by increasing core stiffness

The properties of the movement itself and the speed of core stiffening

The magnitude of core stiffening (stiffer doesn't always mean better, remember: fast and powerful athletes also need to learn how to relax at the right times - like the example of the punches and kicks we used earlier).

First off, I'd like to break this article up into 2 categories, short-term improvements in core stiffness and long-term improvements in core stiffness.

SHORT-TERM IMPROVEMENTS

Short-term improvements or increases in core stiffness, are characterized by improvements seen within the same training session. Known and performed as "core activation" drills among personal training circles, some claim that performing core exercises prior to the main exercises of a workout "wakes up" the core and improves performance on the subsequent exercises. While terms like "wake up" are very arbitrary, it helps to look a potential mechanism by which core activation drills help with short term performance.

Post Activation Potential

Benjamin Lee and Stuart McGill carried out a study in 2017 to measure the effects of short-term isometric training on core torso stiffness and found beneficial results. For the core isometric training protocol, participants performed the plank, side plank and bird dog exercises for 5 sets of 10 seconds - with coaching cues being offered and standardized to all participants. Using both passive and active torso bending trials, the results showed that most participants had reductions in torso deflection and increased core stiffness (more details here).

While this study showed that short-term core stiffness can be increased via isometric core exercises, it doesn't tell us how that core stiffness will transfer to performance in other exercises, or how long this effect lasts. In their discussion, the authors pointed to the fact that the isometric exercises done could have elicited a post activation potential (PAP).

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where strength and rate of force development (power) is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. The most common protocols may include heavy back squats to elicit a PAP effect before sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses before performing ballistic medicine ball pushes/throws. Utilizing the PAP effect is also known as complex training. Here are some examples of exercise pairings, from the NSCA.

Taken from https://www.nsca.com/Education/Articles/Hot-Topic-Post-Activation-Potentiation-%28PAP%29/

For a concise explanation of the potential mechanisms behind PAP and how it works, visit Science For Sport.

Back to the study. While the authors pointed out the PAP mechanism, they acknowledged that their core training protocol, despite improving core stiffness, did not meet the requirements of a "potentiating exercise". In a standard PAP protocol, the potentiating exercise has to be close to max effort, with the recovery time reflecting the nature of exercise. Lee & McGill's (2017) study's core training protocol included 5 sets of non-fatiguing core exercises (only 10 seconds long - bodyweight, no added resistance), so I'd be interested to see if there could be a larger PAP effect if some core exercises are taken to near max effort. Here are some ideas:

Complex Training For Core & Power Exercises

Weighted Planks into Medicine Ball Slams (2-3 minute recovery)

(3-6 complex sets of <30sec weighted planks into 4-8 max effort slams)

Planks are one of the most frequently prescribed core exercises in the fitness and strength training. An easy way to increase the difficulty of the plank is to add extra resistance - perform them weighted. In this complex set, the weighted planks act as the potentiating exercise, increasing the the power output of the slams. While the effort should still be high during the planks, the physiological stress is relatively low compared to for example, a set of heavy front squats; meaning the recovery time should be lower than most heavy compound movements. A recovery time of 2 minutes should be adequate before performing the medicine ball slams.

Squatted Pallof Press Into Rotational Medicine Ball Slams/Throws (1-2 minute recovery)

(3-6 complex sets of 6-8 presses into 4-8 max effort slams/throws)

In this example, I use an anti-rotation exercise to potentiate a ballistic exercise for better power transfer. I also added a small rotation component to what would normally be an anti-rotation exercise (the pallof press) to mimic some of the movements seen in the medicine ball rotation throw. Keep in mind, I still maintain tension on my obliques working and the shoulder girdle stable during the press out and rotation. Recovery time can be anywhere from 1 to 2 minutes.

Other Potential Ideas

Core Stiffness For Powerlifting

Aside from using higher effort complex sets, I have found situations where non-fatiguing core exercises can help improve the quality of a training session. For the last couple of months, I've been using bodyweight planks and shorter weighted plank sets with my powerlifters prior to the main compound lifts . Planks are a good way to emphasize whole body tension (a skill that is required for powerlifting success), to improve the lifters' perception on how active their core for the rest of the training session, and to remind them about the importance of a rigid torso during the powerlifts. Most, if not all of my powerlifters, have found this pre-lifting core work beneficial.

With this protocol, perform several sets of planks at a low RPE (non-fatiguing) to avoid overly fatiguing the core musculature before the compound lifts. More advanced trainees can experiment with planks at higher intensities to elicit a greater PAP response. Slowly increase the intensity of these planks over time to find the sweet spot (balance of volume and intensity).

Core Stiffness For Weightlifting

Another idea I've implemented in the past is the use of higher velocity core stiffening drills to help facilitate weightlifting technique improvements. The catch position of snatches and cleans require a lifter to quickly decelerate the weight by using the prime movers and stiffening the core upon bar contact. I've found depth drop landings or plyometric regression exercises to help with this. Here's a quick example with one of my Strongman/Powerlifting athletes, who was brand new to the Olympic lifts at the time. Used in conjunction with other coaching techniques, he made some good improvements just over the span of 3 months.

Intra-abdominal Pressure (IAP)

If you've spent anytime studying strength training or have spent time in the weight room, you probably heard of the concept of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). Also referred to as "bracing", intra-abdominal pressure is a technique by which a trainee creates 360 degree pressure in the abdominal cavity through controlled inhalation. The created pressure helps stabilize the lumbar spine, reduce the risk of back injuries as well as improve force output. The concepts of core stiffening and creating intra-abdominal pressure are complimentary and much like the core stiffening concepts discussed previously, IAP is not an all or nothing phenomenon.

IAP happens on a continuum, and can vary in intensity and duration depending on the movement requirements of the task. Coaches around the world all stress the idea of creating IAP during strength training, however, not many of them can explain it as well as Chris Duffin (Kabuki Strength) and Stuart McGill. Kabuki Strength describes IAP as a continuum of respiration (breathing) and stabilization (max effort IAP), best represented by a dial.

To give an example, the lumbar stability needs during a 1RM compound lift is different than a sub-maximal activity like running. Running requires just enough IAP to stabilize the torso, while still allowing for optimal breathing. Turn the knob accordingly.

““Improving your ability to select and coordinate the correct dial setting is the key for fluid movement and higher performance in any activity””

long-term improvements

Long-term improvements in core stiffness are characterized by improvements seen over weeks and months of core training. This section will cover the different categories of core training, as well as general training principles that drive long term improvements.

Core Training Categorization

To start, it's best to differentiate between core exercises in order to better analyze their cost-to-benefit ratio. All exercises fall on a general to specific continuum, with the reference points being the movement you want to improve, or the sport/position you're playing - core exercises are no different. Dedicated core exercises can be broken down into several categories:

1. Isometric Core Exercises

Isometric exercises are exercises where force is produced without a change in muscle length. Exercises like planks and hanging L-Sit where you're maintaining your body position are examples of isometric core exercises.

2. Anti-Rotational Core Exercises

Anti-Rotational exercises also fall the "isometric" category. These exercises challenge your ability to stabilize your body to prevent from rotating to any one side, maintaining your body position against an external force or in an imbalanced position. Common exercises include the pallof press, shoulder taps in push up position and many exercises in the half kneeling position. Other great examples not many people know about could be suitcase deadlifts, and uneven farmers walks (videos below).

3. Isotonic Core Exercises (Sagital Plane/Transvere Plane)

Isotonic exercises are exercises that consist of an eccentric and concentric portion - exercises that are not isometric (holds). They can be further broken down into sagital/transverse plane exercises. Sagital plane exercises include standing cable crunches, sit ups and hanging leg raises, while transverse plane exercises involves any exercise that involve torso rotation like cable wood-choppers and medicine ball russian twists.

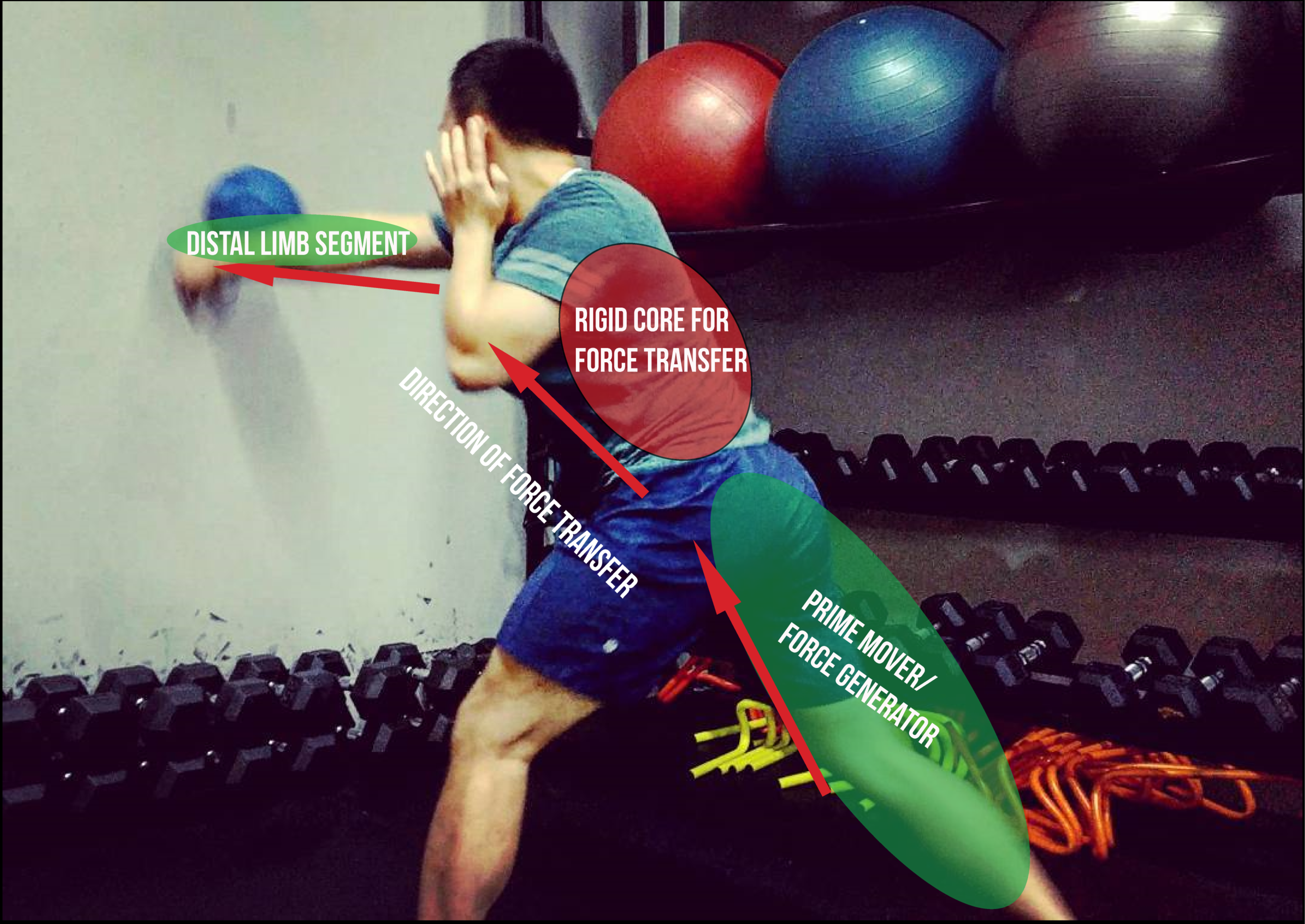

4. Ballistic and Plyometric Core Exercises

Ballistic exercises are concentric-dominant power movements with little to no eccentric muscle action, such as jump squats and explosive push ups. In the realm of core exercises, medicine ball slams, rotational throws can be considered ballistic, but keep in mind the prime movers such as the shoulders and glutes also contribute to the force output.

Plyometric exercises are exercises with a short eccentric-concentric turnover, using the elastic properties of our muscles to improve speed and repeated power output. Many movements like running, repeated jumps/hops and combination striking (in martial arts) are considered plyometric. There are also plyometric exercises designed just to target the core musculature - many of these being rotational. I've posted a few examples below:

Taken from Nick Curson (Speed of Sport)

Taken from Elliot Hulse

Training principles and methods To Improve Performance

Conversations usually go south whenever the topic of "transfer to performance" is brought up; there are many complex variables to take into consideration and everyone seems to have their own definition of "functional" or what exercises will and will not help improve performance. I'll be giving some general tips and training principles of core training that can be applied to various different sports.

Post-activation-potentiation, non-fatiguing core primers and intra-abdominal pressure are all acute techniques that CAN lead to long-term improvements

The research is still not conclusive on whether these are significantly beneficial, but in theory: accumulating small short-term improvements should lead to long term improvements in performance. In other words, if these techniques are performed consistently throughout your training program, they may add up to a measurable increase in strength, power and endurance (whatever you're aiming for). I would also add that the use of PAP and core primers are optional, but in my opinion, IAP is not. I consider IAP a skill that must be learned and utilized consistently in order to effectively produce force, and stay safe doing so.

A combination of general and specific core exercises should be performed

Don't fall into the "functional" trap of prescribing overly-specific exercises. A general exercise that does not fully mimic the movement you're trying to improve can still be beneficial. For example, weighted planks are a great general core exercise to build core strength and endurance that will transfer over to various movements. Once a good base is built, you can start experimenting with more specific exercises. I've included some examples of specific exercises at the end of this article, mainly geared towards improving punch power, but can also be used as core training.

To learn more about the general-specific continuum and how to classify exercises for better training prescription, read my article I wrote on training variation here.

Principle of progressive overload

This is the premise behind improving any type of performance measure. Progressive overloading your core exercises either through a change in position, adding extra resistance, increasing the volume via sets, reps or time. In order to improve, you must progressively add stress to your physiological system, recover from it, and come back stronger.

Improving Core Strength (Slow-Isometric Stiffness)

Core strength, or slower-isometric type core stiffness, is primarily built using isometric and anti-rotation based exercises. Almost every core exercise listed above can be used to improve core strength, but what differentiates training core strength from core endurance is the intensity at which these exercises are performed. Reps should be done in the lower rep range (~<6 reps per set) or 80-95% of 1RM if a 1RM is applicable. Accordingly, intensity/weight progression is what you should be focused on. For example, progressively working towards heavier weighted planks (increasing intensity) instead of increasing the time of which you hold body-weight planks. Improving core strength will benefit every athlete, but strength and power athletes will see the best results.

Improving Core Ballistic/Plyometric/Power Ability (Fast-Recruiment Stiffness)

Core plyometric ability, or what I like to describe as a faster-recruitment type core stiffness, is built through plyometric core exercises and have a higher skill/timing component to it. This is the type of core stiffness I discussed in part 1, that is required for high-impact athletes who perform punching, kicking and striking movements. The ability to contract-relax-contract and produce a fast eccentric-concentric turnover is what defines an athlete with good core power and plyometric ability - both deceleration and acceleration are taken into account.

I gave examples of relatively advanced plyometric core training above (see Nick Curson and Elliot Hulse's videos). A more beginner friendly way to perform these exercises would be to reduce the range of motion on the exercises and reduce the power output until you improve your timing. A drill I found useful are short plyometric medicine ball rotation slams - timing and rhythm are paramount here so develop them before moving onto higher-intensity, higher-effort plyometrics.

Improving Core Endurance

When people think of the word "endurance" they immediately associate that with a low-intensity, long duration training protocol. Don't make the same mistake. Endurance can refer to the ability to maintain a certain power output for an extended period of time OR be able to repeatedly perform high-intensity bouts with little to no drop off in power output from start to finish. I recommend using work-to-rest ratios with your core exercises based on the energy system you want to develop.

Do you want to be able to repeat maximal high-intensity efforts? Use work rest ratios anywhere from 1:20 to 1:30+. For example, 6 seconds of maximum effort tornado ball slams with 2 minutes of complete rest in between sets, for several sets (1:20 work-rest ratio).

Looking to improve anaerobic capacity? Use work-rest ratios around 1:1. For example, 60 seconds of moderately heavy farmers walks with 60 seconds of active rest in between sets (1:1 work-rest ratio).

Looking for longer duration core endurance? Perform lower intensity core exercises for a total of 3 minutes+ at a time with a work-rest ratio of ~2:1. For example, hold a bodyweight plank for sets of 3 minutes with 1.5 minute rests in between. To add some variation to these longer sets, you can also perform 3-4 different core exercises as a circuit for 1 minute each. Over time, increase the duration of each set or the total number of sets (volume load progression at a set intensity).

Using work-to-rest ratios is another tool by which you can use to look at and utilize core training with. It can help you visualize which energy systems are at play, so you can make the adaptations you want to see. Endurance is specific.

Diminishing Returns

More core work means better performance right? Not so fast. Welcome to the principle of diminishing returns. The more you train core stiffness, the less benefits you reap in. I see core stiffness training a lot like maximal strength for sports. There comes a point where more core training does not equate to better performance on the field, court, platform or ring. Core stiffness, much like strength, serves as a foundation on which other important physical attributes are built on - rate of force development, agility, resilience to injury to name a few. Be careful not to allocate all of your time and energy into core stiffness training, while neglecting the development of other skills and attributes.

So how much is enough?

Unfortunately, I don't have a concrete answer for you. This really depends on what sport and movement patterns you're referring to. Core training should fill the gaps of your physical development, and be used in conjunction with sport-specific skill work and strength/power/plyometric training. Being able to competently perform all the movement patterns and core exercise categories listed above is a great start.

Biggest takeaway

If there's one thing you take away from this article, it's that core stiffness training is context-specific and should be thoughtfully prescribed and developed. Core training does not have to be boring, so don't be afraid to get creative. Below is some of my content I've put out on core training, core ballistic training and various medicine ball slam exercises. Thanks for reading!

ARTICLE: Great Core Exercises You're Not Doing

CORE TRAINING VIDEOS:

Bests of 2017

A review of 2017. Happy new year everyone, thanks for the support!

[Biggest Lesson of 2017]

When you run your own business, there is no escaping it. I try my best to put out content for you guys while still keeping some sort of privacy in my personal life, but it's something I always have trouble balancing.

As much I would like this to be MY bests of 2017, I can't escape the fact that I AM GC Performance Training.

From not knowing what content to put out, to having some of my articles recognized by some big names in the industry.

From clients getting injured to athletes hitting their lifetime bests after weeks and weeks of hard preparation.

Day in, day out. It's always a rollercoaster ride.

I'm thankful for the clients and athletes that have given me a chance to work with them, so that I can put food on the table, enjoy the hobbies I enjoy and be part of their journey.

[GCPT Athlete Of The Year] - Mark xu

Mark Xu is a 74kg Junior BCPA Powerlifter

This one was a hard one to pick. Everyone worked hard this year but Mark takes the cake on this one.

He has: Been injured, discouraged from training, dealt with his last year in high school, graduated high school, accepted in a University, remarkably improved his lifting technique and have gotten way stronger than before. All in 1 year.

He's one of my youngest athletes, and it's been a pleasure watching him develop into a more confident athlete. Look forwards to the next year with you bro.

Not taking anything away from everyone else on the GCPT team. I love you all.

[Best Articles Of The Year From GCPT]

5 Part Periodization Series - http://gcperformancetraining.com/gc-blog/periodization101

If there's one thing I think about every day, it's physical/mental development and preparation. That's all periodization really is, planning to develop and prepare in the most effective way possible given past training history and emerging information.

I was (and still am) tired of coaches arguing back and forth on the types of periodization and getting all worked up on specific terms and methodologies so I put a lot of hours writing this article series on periodization to get my thoughts out. If you have time and want to learn more about physical and mental preparation, as well as the variables and nuances involved, please give it a read.

Here are some of my top articles by category:

Powerlifting - "Building Your Base In Powerlifting"

Nutrition - "Nutritional Periodization"

MMA & Combat Sports - "High Performance Training For MMA - Experts Weigh In"

General Fitness - "The Current State Of The Fitness & Training"

[Most Memorable Moment of 2017]

My favorite moment (moments, really) has to be traveling to Asia after 5 years of not leaving North America. It was the first time going on "vacation" since I started my dream of owning a training and coaching business.

Got the chance to experience Japanese and Thai culture & food, as well as revisit the motherland (Hong Kong). Thanks to online coaching, I'm able to keep in touch with my athletes even while i'm away.

Looking forward to more trips in 2018 ;)

[Goals For 2018]

I look to better myself physically and mentally every year, so 2018 will be no different. I've been gradually practicing more and more martial arts this year, and that will definitely pick up in the upcoming year.

Muscle mass, strength, power, endurance, sport-specific skills... I want all of it. ALL OF IT. Bring it on, bro.

Special thanks to all my clients and athletes. Coaches that have helped me improve this year. All of my followers (I've been able to grow from 240 followers to 745 on my GC Performance Training page. Thanks for the love!).

Happy new year!

My Thoughts on the FMS (Functional Movement Screen)

I recently had someone ask me whether getting the FMS certification was worth it. Like many questions, I answered... "it depends".

FMS Certification For Trainers & Coaches: Good Idea? Or Stay Away?

I recently had someone ask me whether getting the FMS certification was worth it. Like many questions, I answered... "it depends".

For those who don't know, the FMS (functional movement screen) is a fitness assessment created to look for "movement dysfunction". The FMS can be a good tool for new personal trainer and coaches to use as an initial assessment and as practice as they become more familiar with human movement. But becoming dependent on an arbitrary set of exercises to understand movement dysfunction and predict injury risk is something many trainers and coaches should avoid as they progress through their career.

Using pre-determined movements and quantifying movement quality is the complete opposite of conscious coaching and dismisses the idea of movement variability.

Conscious coaching requires adaptability and interaction.

Stop staring at your piece of paper; start watching your athletes and patients move. Figure out which movements are required in their sport or daily life because the definition of "functional" movement varies from sport to sport and one environment to the next. Talk to your athlete or patient about their confidence (or uncertainty) about particular body positions or movements. Design well-structured training programs that control for load, fatigue management, and injury reduction. Since your athletes and patients will most likely come from many different backgrounds, conscious coaching and assessment will do heaps more than some standardized test will.

This is not to say I'm against writing anything down. Notes should be taken when necessary.

Instead of writing: "Scored a 2 on the lunge test", a conscious coach will watch their athlete and note: "knee valgus during fast change of direction when running - check hip and leg complex and assess previous injury history and running/agility technique."

Some argue that the fact that FMS can be standardized to help sports teams. Several of studies have come out showing that their findings do not support the "predictive validity of the FMS" and that the FMS does "not relate to any aspect of athletic performance", so using an invalid assessment is stubborn and a waste of precious time, no matter how consistent it is. Can the FMS be useful? Of course. But consider the picture blow:

The FMS is 8% better than a coin toss. Let that sink in.

Like I said earlier, the FMS can be useful for new trainers and coaches. However, the end goal should be to acquire enough knowledge on human movement, motor learning, movement variability and training load to be able to consciously watch our athletes and clients. The FMS is not a game-changer and I would advise you to consider whether or not getting certified will help you towards your goals given your current experience level.

Be adaptable.

Why The Pyramid Works So Well In Fitness

The pyramid works well in the fitness industry because it takes into account priorities, and base building. In an industry where the flashiest and most "advanced" training and dieting programs are being pushed down the throat of the consumers, educating beginner trainees on the importance of simplicity is crucial.

We've all seen training and nutrition principles put into a form of a pyramid before (some examples below), but why a pyramid? Why not a pie chart or a flow chart? Let's discuss.

The pyramid works well in the fitness industry because it takes into account priorities, and base building. In an industry where the flashiest and most "advanced" training and dieting programs are being pushed down the throat of the consumers, educating beginner trainees on the importance of simplicity is crucial.

Priorities

Everything you do in your training and nutrition should be effective and time efficient. Using a pyramid really illustrates what aspects of your training and diet needs the most focus on, and which aspects will give you the most bang for you buck.

Let's take the nutrition & fat loss pyramid for example: 90% of your bodyweight goals will come from just paying attention to calorie intake. Eating less calories than you burn will result in weight loss. However if you're concerned with keeping the most muscle mass as you can for aesthetic, or performance reasons, this is where we move up the pyramid and take into account macro-nutrient distribution (in this case, adequate protein intake), making sure you're hitting your micro-nutrient and fibre needs for good health.

Too many people, too often, major in the minors. Instead of spending the time to count calories, they'll go to the nearest GNC store to find a fat burning supplement that just simply won't work. Again, using pyramids helps you pin point which areas of training or diet to focus on, and which areas are details.

Building a base

The bigger base you build, the higher potential peak you can have. This holds true for performance training and performance nutrition. Athletes and trainees are often impatient and believe they'll progress faster than everyone else. They'll use professional athletes as examples of why to follow the most-intense training program, why they should specialize in their sport early on into their athletic career, and why they should use the most advanced training methods.

They're wrong.

Professionals and high-performers often do NOT specialize early (they play multiple sports growing up and dabble in many different types of training methodologies) and they MASTER THE FUNDAMENTALS!

Using the strength training pyramid for example: trainees make the mistake of spending their energy on intensity, volume and frequency before they develop proper movement quality. Improving technique and movement quality will make everything upstream more effective.

Good movement quality will open you up to a wider array of exercise selections, create consistency and accuracy in your periodized program, as well as set you up for proper strength progressions and ultimately, more advanced training methods.

started from the bottom now we're here

Don't forget about the basics, master the fundamentals and you'll achieve more results than you originally expected, I promise. There's nothing wrong with learning about advanced training or dieting methods, however, if you're a beginner or intermediate trainee, keep things simple and practical.

Amazing Feats Of Strength

A compilation of amazing feats of strength, ranging from powerlifting, gymanstics to rock climbing and martial arts.

We, as trainers and trainees in the fitness industry sometimes have a really biased and skewed perspective of what is considered "strong". With the rise of barbell sports like Crossfit, powerlifting and Olympic weightlifting, it can be easy to forget other forms of strength, beyond the barbell, beyond just numbers.

I get it, lifting a massive amount of weight/external load is impressive and it shows how far our humans neuromuscular system can be pushed. However, one must not forget that strength is specific and involves other variables such as coordination and timing. With that said here are some amazing displays of strength, ranging from powerlifting, all the way to martial arts.

Powerlifting: Ray William's 1005lb Squat

Olympic Weightlifting: Alexey Lochev's 582lb Clean & Jerk

Strongman: Mariusz Pudzianowski's Plane Pull

Strongman: Haftthor Bjornsson's 640kg Log Lift

Wrestling: Aleksandr Karelin

Gymnastics: Yuri Van Gelder (Rings)

Rock Climbing: Alex Honnold

Mixed Martial Arts: Daniel Cormier

Daniel Cormier flips 6'4'' Alexander Gustafsson.

How To Maintain Strength And Muscle Mass While Losing Weight

Even when losing weight, strength and muscle mass can be easily maintained or even improved when proper dieting and training adjustments are made. Here are 2 nutrition and 2 training tips to implement the next time you plan on losing fat:

Many competitive strength athletes and recreational lifters are under the impression that strength and muscle loss is inevitable when losing weight or undergoing a fat-shredding phase. This is often NOT the case, as strength can be easily maintained or even improved when proper dieting and training adjustments are made. Here are 2 nutrition and 2 training tips to implement the next time you plan on losing fat:

Conservative Calorie Deficit

Whenever muscle and strength retention is of concern during periods of weight loss, a conservative calorie deficit should be used. The idea is that rapid bouts of weight loss created by large calorie-restrictions hinders our ability to perform hard training sessions and our ability to recovery from them. This may result in a loss in lean body mass and subsequently, decreased performance.

In 2011, a group of researchers studied the effects of 2 different weight-loss rates on male and female athletes' body composition and sporting performance. The slow weight loss group lost ~0.7% of their body weight per week while the fast weight loss group lost ~1.4% of their body weight per week.* At the end of this weight loss period, it was found that the slow weight loss group retained more muscle mass and performed better on upper body strength tests compared to the fast weight loss group. This could have been from consuming more calories for muscle repair and recovery and lower mental stress from dieting more conservatively, which results in a smaller disruption to their bodies' homeostasis.

Simply put: a slower weight loss rates helps maintain muscle and strength.

Using the example study above (0.7% bw loss per week), most people will want to lose no more than 1lb of bodyweight per week to better maintain their fitness and performance.

*it should be noted that both weight loss groups lost the same amount of the weight. The slow weight loss group dieted for longer to achieve the same weight loss as the fast weight loss group.

Protein Timing and Distribution

Granted you're already consuming an adequate amount of protein to support recovery and muscle growth, implementing good protein timing and distribution practices is the cherry on top of the sundae.

Effective protein timing and distribution practices revolve around the concept of the touted "anabolic window". The anabolic window concept states that there is an optimal time period where our muscles are more sensitive to protein intake, where protein consumption during this time will result in better recovery, and increased muscle growth. While the importance of the anabolic window is sometimes overhyped by the bodybuilding and supplement industry, it DOES exists. Hours following a hard training session, when our muscle's receptors are hypersensitive and there's a surge of hormones and growth factors. This hypersensitivity returns to baseline anywhere from 12-36 hours and is dependent on several variables:

Volume and intensity of training

Duration of the training session

Modality of training (resistance training will induce more micro-tearing of muscle fibers and a greater hormonal response vs. endurance training)

Training status of the individual

It's because of this anabolic window that many fitness professionals recommend drinking a protein shake immediately post-workout. While this is a good practice, many nutritionists and trainers forget or simply do not put enough emphasis on pre-workout nutrition.

Why worry about pre-workout nutrition if the anabolic window exists post-training? Protein transit and digestion time.

A serving of protein consumed prior to training will still be in the process of digestion and absorption HOURS following a training session. In order to fully take advantage of the anabolic window, an adequate amount of protein (>25-40g, more if you're heavier or possess more muscle mass) must be consumed pre-workout in conjunction with a post-workout shake.

Why does this matter and how does it affect muscle retention?

Our body is in a constant state of building, and destroying, anabolism and catabolism. During a calorie-deficit, its crucial to keep net positive muscle protein synthesis (where total protein synthesis > total protein degradation) in order to facilitate proper muscle repair and growth. Evenly distributing your protein intake around the clock helps increase protein synthesis. Think of it as stoking a fire, constantly feeding the fire fuel or wood. Again, none of this will be effective without consistently hitting your daily protein needs (total amount of protein per day).

Increase lifting frequency

Let's get into the the training side of things.

An unwanted side effect from losing weight (for strength athletes anyways) is a change in leverages and biomechanics. When you lose thickness in your thighs and hips, squats, cleans and lower body movements feel different. When you lose thickness in your lats or chest, bench pressing and overhead pressing feels a bit different. Whether its from an altered stretch-reflex or reduced proprioception, losing weight can negatively affect lifting technique, often resulting in a loss of strength.

To combat this problem, I recommend increasing your lifting frequency. Does your squat feel a bit different after losing 20lbs? Start squatting more frequently. Does your overhead press feel a bit iffy since your weight loss? Start overhead pressing more frequently. Much like the stoking the fire analogy used earlier, the more frequently you spend practicing a movement under your new biomechanical circumstances, the more improvements you'll make. Increased frequency and exposure to an exercise will do wonders in terms of motor learning and familiarity.

stick to your training plan

Aside from increasing training and lift frequency, nothing else should really change.

Lifters often take unneeded preventative measures when dieting by overhauling their whole training plan. If you're losing weight via a conservative calorie-deficit, there is no good reason to significantly decrease volume or intensity of training. You should still be able to perform and progress on your training plan despite eating 200-300 calories less each day.

For athletes looking to rapidly lose fat however, the best line of action would be to slightly reduce training volume by either reducing the total amount of sets and reps BUT maintain or even increase intensity. Lifting heavy (relative to your own strength levels) is crucial for stimulating your high-threshold muscle fibers responsible for maximal strength production. Many studies have shown that high intensity training can help maintain muscle mass and strength weeks and even months after detraining/periods of reduced volume.

Ultimately, have trust in your training plan and stay consistent. Don't let dieting stress prevent you from training and avoid the nocebo effect or any preconceived notions that you'll be weaker and smaller after your weight loss diet. Use these 4 tips, train hard, and train smart. Good luck!

Studies discussed:

"Effect of two different weight-loss rates on body composition and strength and power-related performance in elite athletes." Garthe et al. (2011).

"Nutrient timing revisited: is there a post-exercise anabolic window?" Aragon & Schoenfeld (2013).

"Less Is More: The Physiological Basis for Tapering in Endurance, Strength, and Power Athletes." Murach, Kevin, and James Bagley. (2015)

"Physiological and Performance Responses to a 6-Day Taper in Middle-Distance Runners: Influence of Training Frequency." Mujika, I., A. Goya, E. Ruiz, A. Grijalba, J. Santisteban, and S. Padilla. (2002)

"The Effects of Tapering on Power-Force-Velocity Profiling and Jump Performance in Professional Rugby League Players." Lacey, James De, Matt Brughelli, Michael Mcguigan, Keir Hansen, Pierre Samozino, and Jean-Benoit Morin.(2014)Great Core Exercises You're Not Doing #1

Planks and crunches getting boring? Challenge your stabilization and strength with these core exercises you've probably never done before.

Core training is very popular in the field of fitness and strength & conditioning. Along with popularity, comes a lot of misinformation. Core training is more than just doing 1000 sit-ups or crunches hoping your 6-pack will show up the morning after. When core training is done properly, it can be a great way to alleviate lower back pain, reduce chances of injury during sports or daily living activities, as well as give you a strong and resilient mid-section.

I’m sure you’re familiar with planks and hanging leg raises… so what other core exercises are there? I’ll show you a few!

Front Rack Holds

Front rack holds, aka standing planks (that’s what I call them anyways…). Tired of doing regular planks? Try these out.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Use a cross-arm or Olympic-lifting grip

- Keep arms and elbows parallel to the floor

- DO NOT flare your rib cage or chest out

- Tighten your core, engage your glutes and grip the floor with your feet

- Hold for time, take deep breathes intermittently

The great thing about this exercise is being able easily control the load to your liking. The down side is that beginners might find this position uncomfortable on the collar bones or upper chest. In that case, a goblet hold may be a better variation.

Suitcase deadlifts

Yup, this exercise is what it sounds like: picking up a very heavy suitcase. As opposed to a trap bar deadlift where both sides of your body are loaded, suitcase deadlifts challenge unilateral core stability. The goal of this exercise is to prevent your torso from leaning to one side as you lift the weight up. Along with challenging your oblique abdominal muscles, it’s a great way to strengthen your grip.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Hip hinge and squat down to grab the weight

- Control the weight on the way up and on the way down

- Don’t allow your torso to lean excessively to any one side

Uneven farmers walk

If the farmers walk and the suitcase deadlift had a baby, this would be it. The goal of this exercise is to walk straight and to avoid excessive leaning as we are trying to improve core stabilization.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Start off slow to develop stability, increase the walking speed after a few workouts/weeks

- DO NOT flare your ribcage or chest out

- Tighten your core, engage your glutes and grip the floor with your feet with each step

- Pick a larger weight differential (between the 2 kettlebells or dumbbells) to make this exercise more challenging

Tire clean and hold

While this exercise does not exclusively work the core, the core is still very active in preventing your torso from collapsing during each rep. Unconventional, but fun.

Tips to consider when performing this exercise:

- Pick a lighter tire if you’re a beginner trainee

- Tighten your core, engage your glutes, push into the floor with your feet

- Hold the position for 3-5 seconds

Assisted Razor Curls

Is this an ab-rollout variation or is it a hamstring curl variation? Well, actually it’s both! I love this exercise, especially for hamstring injury prevention. As well as challenging your core, you’re putting your hamstrings on blast and working on that eccentric strength. You’ll need a partner to help you out with this one but it’s worth it. (Idea taken from Australian Strength Coach Lachlan Wilmot, thank you!!)

This is one of the more difficult core exercises to perform, so here are some pointers to keep in mind:

- Start the movement off with a hip hinge

- Progress this exercise by reaching further out or hold the position for time (isometric)

Give these exercises a try. Got any questions or feedback? Visit my Facebook and Instagram page down below and leave a comment!

How Much Protein Do You Really Need?

What are the benefits of increasing protein intake and how much do you really need? Find out here!

Protein is an essential macronutrient used to build, maintain and repair tissue in our body. There are different recommendations on protein intake, this article will touch on the factors that should be considered when determining an "optimal" amount.

The current Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.36g/lb of bw (equates to 0.8g/kg of bw). Following these guidelines, a 185lb person is only recommended to consume 67 grams of protein!! Quite far off from the 1g/lb of BW recommendation we often hear from the fitness industry.

The RDA for protein was created for non-exercising individuals to consume enough protein for bodily functions and overall tissue health. However, this amount is not sufficient to meet the needs of athletes undergoing rigorous training . There are several variables involved in calculating protein intake values:

- Body composition (total body weight, especially lean body mass)

- Mode of training (strength vs. endurance vs. mixed)

- Frequency, intensity and volume of training

- Specific body weight goals (losing weight vs. gaining weight)

- Dietary Preferences

For The recreational and Dedicated Strength/power Athlete

Strength athletes want to consume adequate protein for one main reason: to maximize muscle protein synthesis (MPS) in order to to increase muscle mass (hypertrophy). Another benefit of protein consumption is to promote recovery in between training sessions. Supplying enough amino acids to repair our damaged muscle fibers from training is essential to health and making short and long term progress in the gym and on the platform.

Often in the strength training circle, we hear about being in a "anabolic state". What this really means is a positive net protein balance. A positive net protein balance is achieved when dietary protein consumption is greater than protein loss. For strength athletes, many lifters have success with anywhere from 0.8-1.5g of protein per Lb of bodyweight (some even higher, we'll touch on this in a bit). This means a 185lb lifter will consume anywhere from 148g to 278g of protein a day.

So why the large range? It really comes down to dietary preference, training age and current lean body mass.

Dietary Preference: Lifters that love steak, chicken and fish among other protein sources will have no problem consuming these foods on a regular basis. Their protein intakes will be high, by habit/dietary preference.

Training Age & Current Lean Body Mass: The more experienced of a strength athlete you are, the more likely you'll have greater amounts of muscle mass. The more muscle mass you have, the more protein you'll need to consume to match the demands of you body. A muscular, lean, world-class strength athlete may grativate towards the higher end of protein intake recommendations (1.5g/lb of bw), while a beginner trainee on starting strength or other beginner programs will make great progress consuming 0.8g/lb of bw.

High Protein Diets

This naturally leads us to the question, are high protein diets safe? Opponents of high protein intakes will argue high protein diets impair kidney function and decrease bone density. However, it is found that high protein intakes are not detrimental to kidney function in individuals with healthy kidneys to begin with and high protein diets are actually positively correlated with increased bone mineral density (elderly).

There is a series of research studies carried out by Jose Antionio et al, on the effects of the very high protein consumption on health and body composition(1.5-2g/lb of bodyweight). They conclude that there is no evidence a high protein diet is harmful, and that they were favorable for body composition goals and body fat control (even at a calorie surplus; very interesting).

"I'm already consuming protein at 1g/lb of bw, in what scenarios should I further increase my intake?"

Periods of Moderate-Large Caloric Deficits

For most lifters in a 300-400+ kcal deficit, I suggest increasing daily protein intake slightly, perhaps to 1.25g/lb of bw. (please note these numbers are far from concrete, these can vary from individual to individual). Doing this will help maintain lean body mass while losing weight/body fat.

Increasing Satiety During Caloric Deficits

Protein is known to be more satiating and has more of a thermogenic effect (takes more energy to digest) compared to carbs and fats. After a high protein meal, individuals usually feel fuller for a longer. For individuals that struggle with hungry during calorie deficits, eating a plentiful amount of protein-rich sources (and a huge salad of course) may be your answer.

Enhanced Recovery

Do you struggle with muscle soreness, and decreased recovery time in between training sessions? Try increasing your protein intake.

The protein - carbohydrate trade off

More protein in your diet means less room for carbohydrates. Luckily, recreational lifters and dedicated strength/power athletes do not require a high amount of carbohydrates to fuel performance; with the exception of high-volume training. Before you increase your protein intake, consider the following:

- Is your current carbohydrate intake adequate for performance?

- Do you have to prioritize performance in the gym or do you need to improve your rate of recovery in between sessions?

- Are you in a isocaloric state (maintenance)? Are you in a calorie deficit? Calorie surplus?

- *Can you afford to decrease your carbohydrate or fat intake in order to increase protein intake?*

the bottom line

Benefits of protein

- Support overall health

- Support muscle growth

- Repair muscle tissue in between training sessions and in times of muscle injury

- Hunger control and satiation

- Controlling body composition and body fat

0.8 - 1.5 grams of Protein per pound of bodyweight is sufficient

- The lower end 0.8-1.0g/lb of BW for:

Beginners and (maybe) Intermediate Strength athletes

Recreational Lifters

General health and fitness (if you partake in strength and cardio training)

- The higher end 1.0-1.5g/lb of BW for:

Intermediate and advanced athletes

Hunger control and satiation

Athletes in a caloric deficit

Athletes with a dietary preference for protein sources

Protein Distribution

- Multiple meals consisting of >20-30g of protein from high quality sources (whey, egg, beef, fish, soy protein)

- Aim for protein sources with high amounts of Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), this is often what determines protein quality (optimal amount is 3-4g of Leucine)

Any questions? Comment down below or reach out to me on the Facebook page

![[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1559464401554-UTSFUHZQUTNOISFNVX1P/Daryyl-Wong-Court.jpg)