Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]

In part 2 of this article series, we’ll discuss principles and training methodologies that can be used to optimize combat sports training within-session and within the week.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

In part 2 (this part), we will discuss the specifics week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

Read PART 1 on Macrocyclic and Mesocyclic Training Here

the microcyclic layer

Programming on the microcyclic layer is concerned with optimizing training on the weekly level. Given the amount of sessions in a combat sports athletes’ schedule, we must consolidate them by avoiding any interference effects and create systems that can manage training stressors more consistently. Here are some guiding principles and strategies that you’ll find in my S&C programs.

High/low structure

I use a high/low structure to guide the initial parts of my program planning; a system popularized by track coach Charlie Francis to categorize running intensity and it’s affect on speed adaptations.

“High” training days consists of training modalities that require a large amount of neuromuscular-activation, a large energy expenditure and/or a high cognitive load - all stimuli that require a relatively longer period of full recovery (48-72 hours). Conversely, “low” training days are less neurally, bioenergetically and mentally demanding, requiring a relatively shorter period of full recovery (~24 hours).

Adapted to the world of combat sports, all training modalities, from sparring, technique work, heavy bag training to weight room sessions can all be categorized into high and low. This allows us to visualize the training and recovery demands of sessions throughout a full week of training.

Ideally, we would schedule training so that we alternate high and low training days so that the athlete is adequately rested for the most demanding sessions, but the reality of the fight game makes this challenging in practice. Some sessions, on paper, fall in between high and low categories in terms of physiological load. Regardless, using a high/low structure is a great start to help manage training stress within a week of training.

Condensed conjugate method

First of all, the conjugate method (CM), originally created for powerlifting performance by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell uses Max Effort (close to 1RM lifting), Dynamic Effort (low % of 1RM performed in high-velocity fashion and Repetition Effort (moderate % of 1RM performed for ~8-15 reps) all within a training week. The CM is based on a concurrent system (I discussed this in part 1, where training aims to develop several physical qualities within a shorter time frame - week and month).

The first time hearing of the condensed conjugate method (CMM) was from Phil Daru, S&C coach to several elite combat sport athletes out in Florida, USA who adapted the CM method to fit the tighter training schedule of fighters.

What is originally a 4-day split (CM) is condensed into 2 days (CMM). This is what the general structure/training split looks like within a week.

Day 1:

Lower Body Dynamic Effort

Upper Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Day 2:

Upper Body Dynamic Effort

Lower Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Max effort and dynamic effort training are both performed on the same day, however, to mitigate neuromuscular fatigue, they are rotated based on upper body and lower body lifts. If upper body compound lifts like heavy presses and rows are performed that day (max effort), bounds and jumps will be trained for the lower body to avoid excessive overload.

Similar to most concurrent-based training splits, a large benefit comes from the fact that movements are trained within the whole spectrum of the force-velocity curve (see figure below). Max effort training improves the body’s ability to create maximum amounts of force - grinding strength, while dynamic effort trains the body to be able to produce force at a faster rate - explosive strength/strength. Repetition effort is then used to target weak points and to create structural adaptations like muscle hypertrophy and joint robustness.

The CMM also shares some of the drawbacks of concurrent-based training set-ups. Single athletic qualities progress slower since multiple are being developed at the same time, however, this is only a minor issue considering the mixed demands of many combat sports. Certain modifications can be made to the template or perhaps block periodization can be utilized (see Part 1 of the article) if working with athletes that are clearly force-deficient or velocity-deficient (see the next section on velocity-split). Nonetheless, a pragmatic way to organize both high-velocity and slow-velocity exercises within a training week. I’ve had success implementing this type of training split in my combat sports S&C programs.

Velocity-split

Sticking with the theme of a concurrent-based system within the training week, another way to set up a microcycle is using a velocity-split. For example, in a 2-day training split, high-velocity exercises and low-velocity exercises would be trained separately.

Day 1:

Upper Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Lower Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Speed-Strength Exercises (Loaded throws, Olympic Lift deratives, Kettlebell swings, etc)

Day 2:

Upper Body Max Strength Lifts

Lower Body Max Strength Lifts

Repetition Effort Training (70-85% of 1RM)

Isolation Exercises

With concurrent training, we risk pulling an athlete’s physiology in opposite directions. This is avoided by grouping similar stressors together within each training day, throughout the week.

Additionally, this can be used to isolate high- or low-velocity training in order to target the weaknesses within an athlete’s force-velocity profile. Using the example split above, Day 2 would play a more important role in the training of a force-deficient athlete while Day 1 would be more effective for velocity-deficient athletes. We are still training both ends of the spectrum within a week but manipulate the training volume, and therefore emphasizing certain aspects of the training stimuli, to fit the needs of the athlete’s physical profile.

WITHIN-SESSION PROGRAMMING

When training multiple physical qualities within a workout, it is important to perform exercises in an order that optimizes training adaptations and reduces the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue. An effective training session will always start with a comprehensive warm-up routine, raising overall body temperature, warming up the muscles and joints, as well as “waking up” the nervous system so the athlete is ready for the work ahead. After that, we need a set of principles to guide how we will structure our training order.

principle of fatigability

Simply put, exercises that require higher neuromuscular output and physical readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue. These exercises are better performed at the beginning of a training session (after warm-ups) when the athlete is fresh and has all of their physical and mental resources. Max effort, max intent modalities like intensive plyometrics, high effort compound lifts and ballistics all fall under this category.

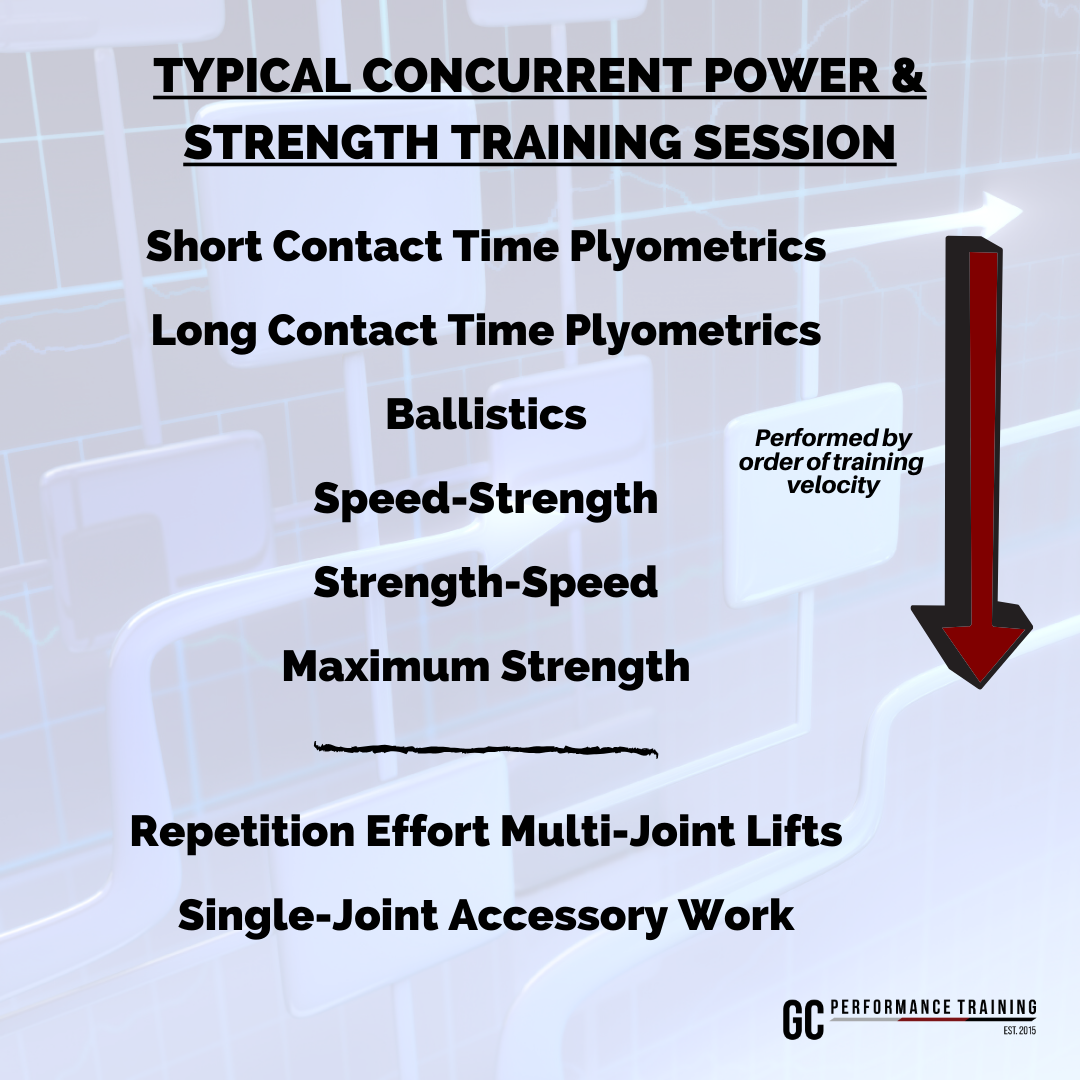

Contrastingly, exercises that require a lesser degree of neuromuscular output like accessory lifts, isolation lifts and stability training can be trained at the end of a session with little to no detrimental effects on training adaptations. If we use this principle to guide exercise order, this is what a typical concurrent power and strength training session might look like:

The same principle can be used if we were train both martial arts and S&C within the same day. Because of the importance of skills training, I would schedule it first. Pre-fatigue can be a tool to improve skill retention and transfer, but in most cases, only hampers skill acquisition and development by making it harder for combat athletes to participate in high quality, deliberate training.

PRIORITY

Prioritization is an exception to the principle of fatigability. An athlete should first perform exercises that are most important to their primary training goal (if they one that is clear-cut). Going back to our athlete is differing athletic profiles, a force-deficient athlete should focus on high-force producing exercises first thing in each training session in order to reap in the most training benefits. Likewise, a velocity-deficient athlete should perform high-velocity exercises before slower movements (the outcome is in line with the principle of fatigability but for different reasons).

Post-activation potentiation and contrast training

Post-activation-potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where rate of force development (RFD)/power is increased due to previous near-maximum neuromuscular excitations. This is another exception to the principles of priority and fatigability, whereby the athlete will deliberately perform heavy compound lifts first even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

I’ve written an article about this topic of within-session planning, covering these principles more in-depth. If you’d like to learn more, read “Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session”.

WRAPPING IT UP

Whenever I create an S&C program for combat sport athletes, I’m always considering all 4 layers of programming. Some of the specific methods I use like type of training-split or the type of volume/intensity undulating I use will change based on the athlete I’m working with, however, most of the governing philosophies (on the macrocyclic level - see Part 1) stay more or less the same.

It’s important for S&C coaches to adapt to information given in front of us, not be limited by scientific dogma, but at the same time, be willing to change and improve our philosophies over time. Since combat sports is a growing industry, so is S&C for combat sports. We must navigate through performance training with nuance.

The learning doesn’t stop there. Here are some combat sports S&C articles that will help you along the way.

Training Session Structure, Single Leg Explosiveness and High/Low Training - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #1

This week’s questions and answers session covers topics such as training session structure, single leg training for power and explosiveness as well as high/low training categorization.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is your philosophy on the structuring of a training session?

The overarching goal behind structuring a training session is to optimize the training adaptations from each exercise within the given session.

First things first, any strength and conditioning training session for a combat sport athlete will start off with a warm-up. I utilize a “RAMP” warm up, the main goal is to raise body temperature, activate muscles, mobilize the joints and potentiate the athlete’s neuromuscular system system to reach the intensities seen in the training session.

The second order of training involves performing exercises that have require a high neuromuscular demand. These are usually high-velocity or high-force output exercises like plyometric jumps and medicine ball slams or heavy compound lifts. The reason why these are performed first is because these training modalities are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigued. In other words, athletes will not be able to reap in the benefits of plyometric and max-strength training if those exercises are placed near the end of the session.

Followed by this, are accessory exercises that are single-jointed or aimed at smaller muscle groups. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Conditioning, depending on the type, will usually be placed at the end of the session.

Here is an example of a full body MMA workout (performed descending order) following these training session structure principles:

RAMP Warm Up (Mobility flow, FRC, Core training, Bodyweight Jumps)

DB Weighted Plyometric Jump

Plyometric Push-Ups

Banded Zercher Squats

Barbell Overhead Press

Cossack Squats + Rotating Lower Back Extension Superset

Banded Rear Delt Flies + Bicep Curl Superset

Aerobic Power Intervals

Cooldown

There are some nuances to structuring a training session however, especially if you’re using methods like post-activation-potentiation or if you’re prioritizing certain power, strength or structural training qualities. I’ve written an in-depth article “Exercise Order - Principle for Sequencing A Training Session”. In this article, I also detail the principles of fatigability and prioritization to help you navigate training session programming. Check it out.

Question #2 - How do you develop single leg or staggered stance explosivity?

Single leg power is first built on a base of bilateral strength and unilateral stability. Before chasing power and explosivity in split or staggered stance movements, ensure that you have spent time building up your strength through squat, deadlift and split squat variations.

Moving forward, some of my favorite exercises for combat sport athletes include lateral bounding exercises, staggered stance kettlebell swings and staggered stance trapbar deadlifts (links included).

The reason I prefer these exercises is because of their ability to transfer over to both striking and grappling performance.

Lateral bounding variations develops lower body power in a way that compliments the in-and-out and angle changing agility demands of striking sports.

Staggered stance variations like kettlebell swings and trapbar deadlifts develops all of the strength and power qualities similar to it’s even-stance counterpart but puts extra emphasis on the back leg. By overloading the back foot and hip, it can possibly enhance force production in back-foot-driven grappling and striking movements such as shooting the double leg takedown or the power-straight and rear power-kick.

Question #3 - What happens if MMA workouts fall in between the high/low categorization of training you’re talking about in ebook?

Many training sessions or training days in reality will fall in between high and low. When this happens, I tend to side on the conservative side and count them as high.

The high/low categorization I mention in my ebook is simply a tool used to help us better understand and balance training stress throughout a training week. The important thing is to consider the training volume and intensity of each training session, the associated recovery cost, and how it will affect performance on subsequent training sessions or the next training day.

If you have a hunch a particular training session or class incurs much more stress than you originally thought, take some readiness data post-training and track fatigue markers like muscle soreness or nervous system readiness through jump or grip testing.

Remember, nothing in the chaotic world of combat sports training is set in stone. It’s great to have a framework to guide you, but this does not replace trial and error and constant refining of the training and planning process.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

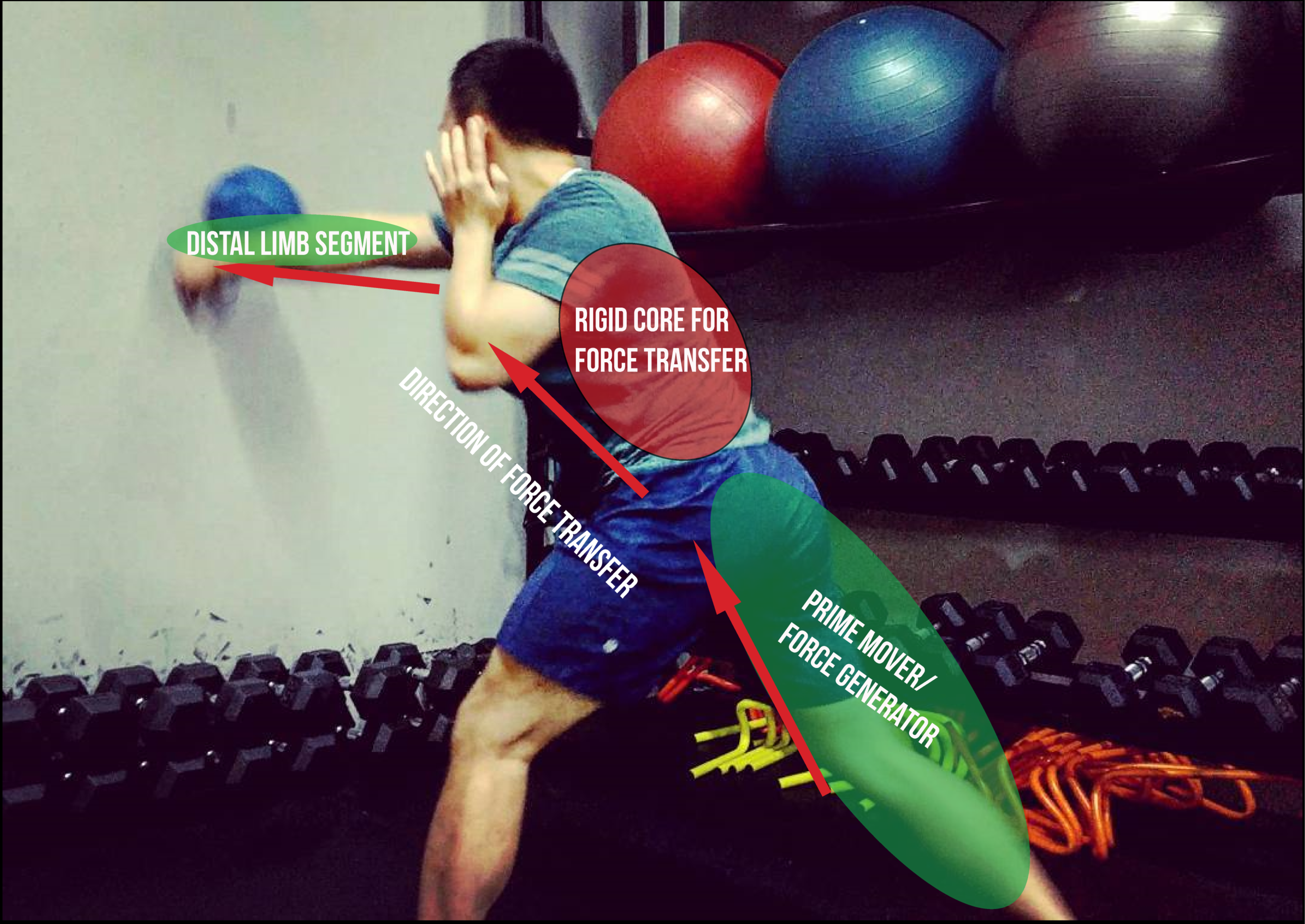

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Given that you are able to select a handful of exercises that have a good chance of influencing strength & conditioning performance measures in athletes, you must be able to sequence each training session with the exercises in the “correct” order.

I say the word “correct” very cautiously as there are no absolute truths or right or wrong in the complex, unpredictable world of human performance. To navigate through the unpredictable nature of training, it pays off greatly to have a set of principles to prescribe and coach by, while still leaving room for flexibility when new information or new prioritizations arise.

Principles for sequencing a training session

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Fatigability

The principle of fatigability accounts for each exercise modality’s sensitivity to neuromuscular fatigue. Exercises that require high nervous system output and higher physiological and psychological readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue.

One explanation for this lie in the physiological characteristics of our muscle fibers. Fast-twitch, type 2 muscle fibers possess higher contractile speeds and a higher potential to produce contractile force. For this reason, they are favored during exercises that demand high-velocities and high-force outputs. Type 1 muscle fibers in contrast, are more resistant to fatigue due to their higher oxidative properties but as a consequence, have lower force-producing capabilities.

The larger velocity and force demands, the shorter they can be sustained for.

Following the principle of fatigability, exercises modalities like plyometrics, ballistic and maximum strength should then be performed first if they are to be trained concurrently within a training session.

Accessory exercises that are single-joint in nature, aimed at smaller muscles groups can be placed in the latter half of a training session. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Priority

The principle of priority is highly correlated to the principle of fatigue, and states that an athlete should be performing the exercises that are most important to their primary training goal, at a time when they have the most resources to do so. From an energetic and fatigue standpoint, this usually means the beginning of a training session when the athletes are at their highest point of psychological and physiological readiness (after a proper warm-up of course).

Not including the athletes at the ends of the endurance-strength spectrum (like endurance cyclists and powerlifters) the primary goal of many athletes is to develop higher rate of force development (RFD) / power and transfer this improved athleticism to sport-specific skills. Strength training is a secondary goal but must also be considered as it is crucial for second order effects such as injury risk reduction, slower-velocity force production and carryover to RFD training.

If your primary goal however, is to develop maximum strength, heavy compound lifts should come before high-velocity training. This sequencing does not follow the principle of fatigability, but satisfies the principle of prioritization.

the contrast training exception

Contrast training offers an exception to the principles of fatigability and priority, where heavy compound lifts are deliberately performed first to elicit a post-activation-potentiation (PAP) effect, even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where RDF/power is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. You’ve probably seen protocols utilized by strength & conditioning coaches such as heavy back squats paired with sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses paired with ballistic medicine ball throws and slams.

While the most common form of potentiating modality is maximum strength (85-100% of 1RM or <0.5m/s bar speed if you’re using VBT), I, along with other coaches I’ve communicated with, have had success using strength-speed exercises as a potentiating modality. Exercises like weighted trapbar jumps or Olympic weightlifting variations, loaded to achieve velocities around 0.75 - 1.0m/s.

Isolating Before Integrating in Rehabilitation & Return-To-Play settings

In the context of rehabilitation, priority is given to exercises that are aimed towards rebuilding the capacity of the injured muscle, joint, tendons and/or ligaments. In my return-to-play protocols for my athletes, I will place single-joint, stability and balance-based exercises in the beginning of the training session before integrating them back into strength and plyometric exercise regressions.

Since our main goal is rebuilding the athletes’ capacities, velocities and force-outputs are not expected to be high, therefore there will be little detrimental effects to placing those exercises last.

Anecdotally, my athlete’s have reported feeling more confident in performing strength and plyometric exercises after an extended warm up and emphasis on their injured area.

Wrapping it up

Exercise sequencing should be individualized on an athlete-by-athlete basis using the principles of fatigability and priority, while taking into account special circumstances like performing advanced training protocols or managing injured athletes. While some can argue exercise selection has a larger impact influencing performance outcomes and that exercise order is of less importance, using principles for exercise sequencing bring a consistent and strategic approach to the design and implementation of a training session that cannot be overlooked by high performance athletes and coaches.

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)