Comprehensive RAMP Warm Up for Muay Thai Training

The traditional Muay Thai warm-up that many fighters comfortably default to leaves a lot of stones unturned when it comes to getting the most out of your Muay Thai training. Here is a 3-phase comprehensive Muay Thai warm-up to ensure you’re performing at your best each session.

You walk into the gym. Perform 2-3 of your favorite stretches. Skip rope for couple of minutes with the heavy thai ropes. You shadow box a few rounds then jump straight into class.

Does this sound like you?

The traditional Muay Thai warm-up that many fighters comfortably default to leaves a lot of stones unturned when it comes to getting the most out of your Muay Thai training.

Primo Fightwear, Fight by Science and I have teamed up again to bring you the training solution - a comprehensive 3-phase Muay Thai warm-up based on the RAMP protocol commonly used in strength & conditioning circles.

Our objective was to create a time-efficient, streamlined warm-up that prepares fighters for the training demands of Muay Thai training, drilling and sparring.

This is video shows snippets of each exercises, in each warm-up phase. For details on warm-up duration, read further.

The RAMP Protocol

The RAMP protocol is a principle-based warm-up method to prepare athletes for any training sessions. The acronyms are as follows:

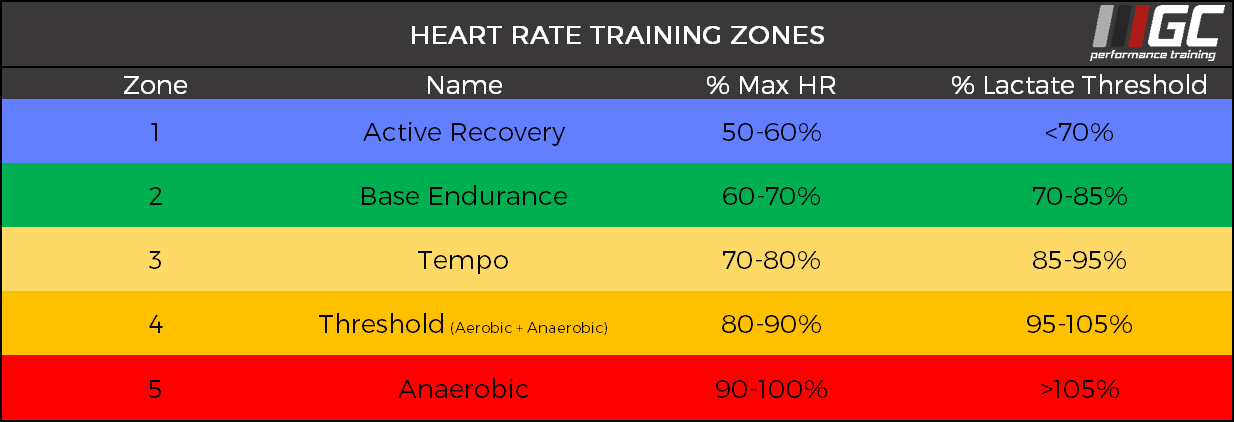

(R)AISE BODY TEMPERATURE

(A)CTIVATE MUSCLES

(M)OBILIZE JOINTS

(P)OTENTIATE TO REACH INTENSITIES SEEN IN THE TRAINING PROGRAM

While there is a lack of data showing that warm-ups reduce the risk of injury, many coaches and athletes understand that by gradually increasing exercise/training intensity, we give our body and mind time to acclimate to the training environment. Anecdotally, fighters perform better mentally and physically following a comprehensive warm-up.

For this Muay Thai warm-up, we’ve separated it into 3 different phases.

Phase 1 - raise temperature & mobilise

The main objective of Phase 1 is to raise the core body temperature and simultaneously mobilise the joints. Exercises and movements in phase 1 are considered lower intensity. We’ve selected exercises in the order of head-to-toe - first warming up the neck as well as eyes, moving on to the shoulders, hips and lower legs.

Phase 2 - Activation

Phase 2 involves exercises that stimluate the muscles involved in striking, clinching and stabilisation. Single leg stabilisation is paramount to kick and kneeing performance in Muay Thai, this is addressed by one of our favorite exercises, the single leg kick outs into hip airplane. The cork screw push ups and mountain climbers develops many of the same shoulder and core muscles used in clinch training.

Phase 3 - Potentiation

Potentiation refers to the excitatory response of the neuromuscular systems following a high-intensity training stimulus. By “waking up” the nervous system prior to training, athletes are expected to show a higher degree of power and reactivity in their padwork, drilling and sparring. In our warm-up, this is addressed by the use of plyometric exercises - progressing from plyo pogo jumps in various stances to a plyo pogo flying knee exercise.

warm-up duration and exercise selection

This RAMP protocol slowly introduces exercise intensity and is a streamlined way to ensure you’re performing at your best within any given training session. Depending on your familiarity with the exercises, each phase should take anywhere from 4-6 minutes to perform. For Phase 1, perform exercises for 20-30 seconds per variation. For Phase 2, perform anywhere from 8-15 repetitions, and lastly for Phase 3, perform 1 set of plyometric pogo jumps in each direction. Aim to finish this RAMP protocol warm-up routine in 15 minutes.

This RAMP Muay Thai warm-up is a blueprint, its open to adjustments and different exercise selection, feel free to add in some of your mobility, core or plyometric exercises - just follow the principles of the RAMP protocol.

Perform this warm-up consisently throughout the training week and you’ll see improvements in your physical and mental readiness during your Muay Thai Kickboxing pad work, drills and sparring.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD

Want to learn more about exercise selection for combat sports?

Chapter 7 of my Strength & Conditioning for combat sports eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Plyometric Development for Muay Thai & Kickboxing

Plyometric movements involve a pre-stretch of the muscle-tendon unit in order to create a higher rate of force development. It is crucial to develop this ability in the sport of Muay Thai and Kickboxing as many blocking, kicking and kneeing techniques are plyometric in nature.

This article to brought to you by

Geoffrey Chiu

GC Performance Training Owner & Coach

Ricardo Alvarez

Lumpinee/Rajadamnern Stadium Muay Thai Fighter

Primo FightWear

Use GCP10 at check out for 10% OFF some of the best modern training gear in the industry today.

Plyometric movements involve a pre-stretch of the muscle-tendon unit in order to create a higher rate of force development. It is crucial to develop this ability in the sport of Muay Thai and Kickboxing as many blocking, kicking and kneeing techniques are plyometric in nature.

In this article, we will use continuous plyometric kicks, that we see often in Muay Thai training, as the prime example of plyometrics in action, as well as offer several plyometric progressions you can incoporate into your strength & conditioning program to develop your speed and reactive strength on the mats and in the ring.

This article and the exercise progressions provided solely focus on developing the physical attributes required for high-level continuous kicking, blocking and more advanced, reactive-combinations.

However, it is important to keep in mind that the number one and most important step to fast and powerful kicking is technique.

Stepping in with the pivoting foot,

Whipping your leg and turning your hips

Swinging the same side arm to project the kicking leg for counter-balance.

If you've ever worked with a high-level Muay Thai or striking coach, you will have heard that "power and speed comes from balance". Balance is key.

From a physical performance lens, continuous kicking is a highly plyometric ability, and there are further improvements we can drive through S&C training outside of technical practice. The key is developing tendon stiffness in the lower leg as well as the contraction-relaxation speed of the hip flexors.

Increased tendon stiffness is an adaptation that comes from progressive plyometric training, benefiting many striking athletes as they will be able to possess faster ground contact times (faster kicks, faster blocks), increase their rate of force development, and maintain their “spring in their step” for a longer duration within a given fight.

exercise progressions

Plyometric Progression Series #1 - Plyometric Pogo Jumps performed in Bilateral Stance, Fight Stance and Switching Stances. While considered an extensive variation in the world of S&C, these are higher amplitude relative to the jumping intensity most Muay Thai athletes get from skipping rope and an ability I find that many fighters lack in Muay Thai.

Plyometric Progression Series #2 - Continuous blocks to pair a plyometric action of the lower leg with the flexion of the hips. A rudimentary stage to building the rhythm and coordination needed for continuous kicks.

Plyometric Progression Series # 3 - Alternating kicks and blocks, the last step of the progression before chaining your kicks together. The use of the block acts as a buffer to allow you to regain the rhythm and ground contact time to execute your kicks. If you're an experienced Muay Thai fighter/kickboxer with little experience in plyometric training. We recommend investing time into the extensive variations seen in Series #1 and #2 for several weeks before moving onto the last progression.

Programming Recommendations

Plyometrics, like most high neuromuscular-demand modalities of training, are best performed at beginning of the training session, after an comprehensive warm-up. To reap the biggest benefits of plyometric training, fighters should be performing these fresh and non-fatigued. For more explanations, read this article on exercise order to learn how to optimise your training sequencing.

If you’re an experienced fighter by have limited experience in plyometric training or dedicated S&C training in general, it is recommended you start by limiting your jump height and perform a higher number of repetitions.

Plyometric Pogo Jumps (Bilateral Stance, Fight Stance, Switching Stances)

Weekly Frequency: 2-3x a week

Sets x Reps: 3-4 Total Sets x 16-20 repetitions per training session

A rule of thumb on jump height for these plyometric pogo jump variations - higher than your skip rope jump height, but lower than your max effort jump. Focus on quick ground contact times and let your feet and ankles do most of the work.

Plyometric Continuous Blocks

Weekly Frequency: 2-3x a week and/or can be incorporated into Muay Thai Training

Sets x Reps: 2-3 sets each leg x 16-20 repetitions per training session

Alternating Kicks & Blocks

Weekly Frequency: Incoporated into Muay Thai training

Sets x Reps: 2-3 sets each stance x 10 repetitions or done in clusters of 3-5 repetitions

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD

Want to learn more about exercise selection for combat sports?

Chapter 7 of my Strength & Conditioning for combat sports eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]

In part 2 of this article series, we’ll discuss principles and training methodologies that can be used to optimize combat sports training within-session and within the week.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

In part 2 (this part), we will discuss the specifics week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

Read PART 1 on Macrocyclic and Mesocyclic Training Here

the microcyclic layer

Programming on the microcyclic layer is concerned with optimizing training on the weekly level. Given the amount of sessions in a combat sports athletes’ schedule, we must consolidate them by avoiding any interference effects and create systems that can manage training stressors more consistently. Here are some guiding principles and strategies that you’ll find in my S&C programs.

High/low structure

I use a high/low structure to guide the initial parts of my program planning; a system popularized by track coach Charlie Francis to categorize running intensity and it’s affect on speed adaptations.

“High” training days consists of training modalities that require a large amount of neuromuscular-activation, a large energy expenditure and/or a high cognitive load - all stimuli that require a relatively longer period of full recovery (48-72 hours). Conversely, “low” training days are less neurally, bioenergetically and mentally demanding, requiring a relatively shorter period of full recovery (~24 hours).

Adapted to the world of combat sports, all training modalities, from sparring, technique work, heavy bag training to weight room sessions can all be categorized into high and low. This allows us to visualize the training and recovery demands of sessions throughout a full week of training.

Ideally, we would schedule training so that we alternate high and low training days so that the athlete is adequately rested for the most demanding sessions, but the reality of the fight game makes this challenging in practice. Some sessions, on paper, fall in between high and low categories in terms of physiological load. Regardless, using a high/low structure is a great start to help manage training stress within a week of training.

Condensed conjugate method

First of all, the conjugate method (CM), originally created for powerlifting performance by Louie Simmons of Westside Barbell uses Max Effort (close to 1RM lifting), Dynamic Effort (low % of 1RM performed in high-velocity fashion and Repetition Effort (moderate % of 1RM performed for ~8-15 reps) all within a training week. The CM is based on a concurrent system (I discussed this in part 1, where training aims to develop several physical qualities within a shorter time frame - week and month).

The first time hearing of the condensed conjugate method (CMM) was from Phil Daru, S&C coach to several elite combat sport athletes out in Florida, USA who adapted the CM method to fit the tighter training schedule of fighters.

What is originally a 4-day split (CM) is condensed into 2 days (CMM). This is what the general structure/training split looks like within a week.

Day 1:

Lower Body Dynamic Effort

Upper Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Day 2:

Upper Body Dynamic Effort

Lower Body Max Effort

Repetition Effort Focusing On Weaknesses

Max effort and dynamic effort training are both performed on the same day, however, to mitigate neuromuscular fatigue, they are rotated based on upper body and lower body lifts. If upper body compound lifts like heavy presses and rows are performed that day (max effort), bounds and jumps will be trained for the lower body to avoid excessive overload.

Similar to most concurrent-based training splits, a large benefit comes from the fact that movements are trained within the whole spectrum of the force-velocity curve (see figure below). Max effort training improves the body’s ability to create maximum amounts of force - grinding strength, while dynamic effort trains the body to be able to produce force at a faster rate - explosive strength/strength. Repetition effort is then used to target weak points and to create structural adaptations like muscle hypertrophy and joint robustness.

The CMM also shares some of the drawbacks of concurrent-based training set-ups. Single athletic qualities progress slower since multiple are being developed at the same time, however, this is only a minor issue considering the mixed demands of many combat sports. Certain modifications can be made to the template or perhaps block periodization can be utilized (see Part 1 of the article) if working with athletes that are clearly force-deficient or velocity-deficient (see the next section on velocity-split). Nonetheless, a pragmatic way to organize both high-velocity and slow-velocity exercises within a training week. I’ve had success implementing this type of training split in my combat sports S&C programs.

Velocity-split

Sticking with the theme of a concurrent-based system within the training week, another way to set up a microcycle is using a velocity-split. For example, in a 2-day training split, high-velocity exercises and low-velocity exercises would be trained separately.

Day 1:

Upper Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Lower Body Plyometrics & Ballistics

Speed-Strength Exercises (Loaded throws, Olympic Lift deratives, Kettlebell swings, etc)

Day 2:

Upper Body Max Strength Lifts

Lower Body Max Strength Lifts

Repetition Effort Training (70-85% of 1RM)

Isolation Exercises

With concurrent training, we risk pulling an athlete’s physiology in opposite directions. This is avoided by grouping similar stressors together within each training day, throughout the week.

Additionally, this can be used to isolate high- or low-velocity training in order to target the weaknesses within an athlete’s force-velocity profile. Using the example split above, Day 2 would play a more important role in the training of a force-deficient athlete while Day 1 would be more effective for velocity-deficient athletes. We are still training both ends of the spectrum within a week but manipulate the training volume, and therefore emphasizing certain aspects of the training stimuli, to fit the needs of the athlete’s physical profile.

WITHIN-SESSION PROGRAMMING

When training multiple physical qualities within a workout, it is important to perform exercises in an order that optimizes training adaptations and reduces the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue. An effective training session will always start with a comprehensive warm-up routine, raising overall body temperature, warming up the muscles and joints, as well as “waking up” the nervous system so the athlete is ready for the work ahead. After that, we need a set of principles to guide how we will structure our training order.

principle of fatigability

Simply put, exercises that require higher neuromuscular output and physical readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue. These exercises are better performed at the beginning of a training session (after warm-ups) when the athlete is fresh and has all of their physical and mental resources. Max effort, max intent modalities like intensive plyometrics, high effort compound lifts and ballistics all fall under this category.

Contrastingly, exercises that require a lesser degree of neuromuscular output like accessory lifts, isolation lifts and stability training can be trained at the end of a session with little to no detrimental effects on training adaptations. If we use this principle to guide exercise order, this is what a typical concurrent power and strength training session might look like:

The same principle can be used if we were train both martial arts and S&C within the same day. Because of the importance of skills training, I would schedule it first. Pre-fatigue can be a tool to improve skill retention and transfer, but in most cases, only hampers skill acquisition and development by making it harder for combat athletes to participate in high quality, deliberate training.

PRIORITY

Prioritization is an exception to the principle of fatigability. An athlete should first perform exercises that are most important to their primary training goal (if they one that is clear-cut). Going back to our athlete is differing athletic profiles, a force-deficient athlete should focus on high-force producing exercises first thing in each training session in order to reap in the most training benefits. Likewise, a velocity-deficient athlete should perform high-velocity exercises before slower movements (the outcome is in line with the principle of fatigability but for different reasons).

Post-activation potentiation and contrast training

Post-activation-potentiation (PAP) is a phenomenon where rate of force development (RFD)/power is increased due to previous near-maximum neuromuscular excitations. This is another exception to the principles of priority and fatigability, whereby the athlete will deliberately perform heavy compound lifts first even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

I’ve written an article about this topic of within-session planning, covering these principles more in-depth. If you’d like to learn more, read “Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session”.

WRAPPING IT UP

Whenever I create an S&C program for combat sport athletes, I’m always considering all 4 layers of programming. Some of the specific methods I use like type of training-split or the type of volume/intensity undulating I use will change based on the athlete I’m working with, however, most of the governing philosophies (on the macrocyclic level - see Part 1) stay more or less the same.

It’s important for S&C coaches to adapt to information given in front of us, not be limited by scientific dogma, but at the same time, be willing to change and improve our philosophies over time. Since combat sports is a growing industry, so is S&C for combat sports. We must navigate through performance training with nuance.

The learning doesn’t stop there. Here are some combat sports S&C articles that will help you along the way.

Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high-performance combat sport athletes.

Given the complexities of combat sports performance, strength and conditioning programming must match the demands of the training environment by being adaptable and holistic. In order to achieve this, programming must consider all layers and timelines of training.

Programming and training periodization happens on 4 time scales (or layers) - Within session, on the microcyclic scale, mesocyclic scale and the macrocyclic scale. Each layer can be considered the lenses of which the S&C coach views training and physical preparation and must be planned accordingly.

In this article, we’ll discuss several strategies and philosophies I use when preparing combat sport athletes, which layers they can be utilized in and how a better understanding of programming can help us more effectively coach high performance combat sport athletes.

Some of the concepts I talk about will be familiar to those who have read my eBook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”, while others maybe new to some of you.

This programming article series will be split into 2 parts.

In part 1 (this article), we will start with a low resolution view of training, in other words, the bigger picture. We will cover big concepts that guide our decisions when it comes to long-term athletic development and month to month training.

In part 2, we will work our way down to the specifics like week to week and day to day programming (higher resolution view).

READ PART 2 ON MICROCYCLE AND WITHIN-SESSION PLANNING PROGRAMMING HERE

the MAcrocyclic layer

In training periodization, the macrocycle is the largest division of training periods, usually several months in length or even a years. When planning on the macrocyclic layer in combat sports, we are concerned with the long-term development of athletes. What the overall career trajectory looks like (considering factors like training and competition age) as well as overall athletic development/progression from fight to fight.

Below are some philosophies and frameworks I use to govern development on the macrocyclic level.

LTAD Model

The long-term athletic development model (LTAD) model is a framework created by Dr. Istvan Balyi to guide the participation, training and competitive aspects of sports and physical activity throughout different stages of development for any athlete.

No matter what stage an athlete comes into the sport, a base must be built for performance potential to flourish in the future. Whether your athletes’ goal is to compete in boxing, wrestling or Judo in the Olympics, or turn to a career in prize fighting for international organizations such as the UFC or One Championship, a coach must see S&C as a long-term investment. Coaches that partake in short-term thinking - disregarding joint health, brain health and overall athletic longevity do nothing but limit the potential of an athlete.

Skill Practice Rules All

The skill practice rules all paradigm acknowledges that skill is the most important aspect of combat sports, rather than physical ability. S&C coaches new to the combat sports world are hesitant on adopting this philosophy (the ones who do fail to manifest this in their programming) as many of them view high performance training through a purely physical and bioenergetic point of view - thinking that maximum strength, power and great endurance (as objectified through lab testing numbers) is what ultimately influences the outcome of a fight.

However, by undervaluing sport-specific skills such as pattern recognition, tactical strategies and fight experience, these coaches make mistakes in the training process that sacrifices skill development and expression for superficial strength and power gains.

Without getting into too much detail, I’ve used this skill practice rules all paradigm to influence my programming so that training stress is distributed more optimally throughout training camps and S&C plays a supplementary role, allowing skill expression to shine on the night of a fight.

If you’d like to learn exactly how I apply this into my S&C programs, I highly recommend you check out the eBook I mentioned earlier.

The Barbell Strategy

Originally a financial investment strategy, the barbell strategy adapted to S&C involves utilizing “low-risk” training methodologies as the main driver behind performance improvements; only prescribing special developmental exercises and “high-risk” exercises when the foundational bases have been thoroughly covered.

With the rise of social media and wild exercise variations promising transfer to the sport, it’s easy to get lost and major in the minors. Landmine punches and brutal conditioning circuits have a place in combat sports S&C but plays a very small role in driving meaningful improvements in fighters.

As a rule of thumb, 80-90% of time should be invested in “low-risk” exercises, and the rest 10-20% into more specialized training. However, don’t fall into the trap of thinking “low-risk” exercises are don’t drive any improvements in sports performance or that they are picked blindly, they should still be selected with the physical demands of the specific sport in mind. A comprehensive needs-analysis of the sport needs to be performed beforehand. Given the limited time I may have with a fighter (2-3 sessions a week), I must select exercises that have a favourable cost-to-benefit ratio.

Looking at the bigger picture, the barbell strategy keeps my programming and exercise selection process grounded by reminding me what improvements I can realistically make with combat fights as an S&C coach and what influence I have over the training process.

Agile Periodization

This is a term coined by S&C coach Mladen Jovanovic. As described by Mladen:

“Agile Periodization is a planning framework that relies on decision making in uncertainty, rather than ideology, physiological and biomechanical constructs, and industrial age mechanistic approach to planning” (Jovanovic, 2018).

Agile periodization represents a training philosophy that’s based on the uncertainty of human performance and one that permeates multiple layers of my programming and planning.

Rigid periodization models that we S&C coaches learn from textbooks and university classes unfortunately have little success given the unpredictability of the real-world and the volatility of combat sports training schedules, competition dates and career trajectories. Furthermore, mindlessly following scientific dogma and abstractions give us a false sense of predictability and stability in the training/planning process.

While we still need to set objective long-term goals and have a vision of what success looks like for our high-performance athletes, the agile periodization framework encourages simultaneous bottoms-up planning: what does the next best step look like given the athletic and environmental constraints in front of us? Does the long term goal change with the new information we’re receiving about the athlete and their progress?

The mesocyclic layer

Mesocyclic planning is concerned with how training variables change from month to month - most of these strategies have fancy names and are ones you normally hear when reading about training periodization.

The overarching goal with mesocyclic planning is to create a training program that bests develops the athletic qualities a combat athlete needs in order to excel at their sport. Whether these qualities should be trained simultaneously, sequentially or in a specific order is what makes one periodization model different than the other.

Let’s explore a few options.

Block Periodization

Commonly confused with programs that simply have “blocks” or “phases” of training, block periodization (BP) is a specific periodization strategy popularized by soviet coaching figures like Verkoshanksy, Bondarchuk and Issurin (article here on a review on different types of training periodization). BP consists of distinct blocks of training aggressively targeting certain physical qualities, such as maximum strength, or plyometric ability (and doing the bare minimum to attempt to maintain other qualities). The basis behind BP is that elite-level athletes who are reaching the functional limits of their physical performance require highly concentrated training loads in order to further increase performance. This becomes problematic when translating it to the world of combat sports training. Here’s why:

Imagine a 4-week block dedicated to increasing maximum strength where the majority of your weight room training volume comes from heavy lifts above >85% of 1RM. The lack of a high-velocity stimulus combined with the fatigue incurred throughout this block will unquestionably hinder an athlete’s ability to develop new skills on the mats or clock in high-quality sparring sessions.

The physical demands of combat sports are not extreme (compared to pure-strength or pure-endurance sports), what’s important is improving key qualities slowly over time while still maintaining physical and mental energy to excel in the practice room - where it counts.

It’s a good idea to separate training into distinct blocks/phases with clear goals, However, implementation of BP, characterized by aggressive investments into single traits and heavily reliance on cumulative and residual training effects, is best left for sports like cycling and powerlifting.

Triphasic Training

Triphasic training, popularized by Cal Dietz, also shares some elements of block periodization, where each block heavily emphasizes the eccentric, isometric and concentric (3 phases - triphasic) muscle actions sequentially to improve speed and power at the end of the block.

Typically, a general preparation phase (GPP) is done prior to jumping into a 6-week triphasic training phase consisting of 2 weeks of eccentric focus, 2 weeks of isometric focus and 2 weeks of concentric focus. This is all capped off with a high velocity peaking/realization block lasting several weeks (depends on the athlete/sport/schedule).

Much like block periodization, triphasic training requires adequate preparation time before a fight or competition and can run into the same problems that BP does, of sacrificing quality of skills training in order to further build physical abilities.

Some coaches have made this work, notably William Wayland of Powering Through Performance, who adapted the triphasic model to MMA athletes, compressing the model and by utilizing supramaximal loading. William breaks it down much better than me so I suggest reading up on it here: “Applying The Compressed Triphasic Model with MMA Fighters”.

Concurrent Method

Like the name suggests, this method involves developing multiple physical qualities concurrently, from month to month. The emphasis on each quality is not implemented as aggressively as it would be in BP or a triphasic set up, so it allows for more programming flexibility - changing intensities and volumes where the S&C coach sees fit (see agile periodization).

By training concurrently, the training stimulus is spread amongst all physical qualities (endurance, strength, plyometric ability, power-endurance, etc) - no physical trait is being neglected, therefore an athlete’s physical readiness remains relatively stable from month to month. A potential downside to this method is that if we’re spreading the training volume thin amongst different traits, we risk watering down the training process and end up not making any tangible process in each area.

Contrastingly, this coincides with the concept of minimal-viable program (MVP) brought up by Mladen Jovanovic, a concept that states that a program that covers all areas will, over time, tell us what changes need to be made based on strengths, weaknesses and any data that comes out of that. Each subsequent training phase will then be modified to suit the needs of the athlete.

These paradigms and philosophies that occur on the macro- and mesocyclic level govern the way we view physical preparation for combat sport athletes, also affecting the decisions we make downstream. In part 2, we will go over strategies we can apply on the microcyclic level and within any given S&C session. (Click here to read part 2).

Squats vs. Trapbar Deadlift, Hypertrophy Training and Plyometrics - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #2

This week’s topics discuss the differences between squats and trapbar deadlifts in a training program, the use of a “hypertrophy phase” for combat athletes as well as how to introduce plyometrics in a fighter’s training.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is the difference between squats and trapbar deadlifts? They both have similar joint angles.

To the naked eye, they have similar joint angles - especially if you’re using the high handles of a trap bar, meaning you’re “sitting” much deeper into the deadlift. Even if this is the case, squats should have a much larger degree of knee flexion, stimulating more of the distal quadriceps and lower leg muscles.

In terms of programming, there are distinct scenarios where I would use one over the other.

The trapbar deadlift is one of the exercises in the weight room that allows an athlete to lift the most weight. Because of this, I use this to build systemic, full-body strength through high-intensity loads. Although the degree of knee flexion is larger than other variations like the conventional or Romanian deadlift, an emphasis is still being put on the muscles of the mid- and lower-back. Trapbar deadlifts play a big role in improving “pulling-strength” in my combat sport athletes.

In contrast, when I want to build more robust knees and lower-body “pushing-strength”, I prescribe squats. Front squats, safety bar squats, back squats, heels-elevated cyclist squats; any variation that I can load safely and effectively with my athletes and achieve the deep knee flexion angles we want to see in order to develop quad strength.

QUESTION #2 - How would you structure hypertrophy phase while doing MMA?

I wouldn’t. Muscle hypertrophy is rarely a training goal for combat athletes, unless they’re trying to move up a weight class and even then, that is better performed over the span of several months or years, not through a 8 or 12 week phase.

If you find yourself in that position, the best options are to slowly increase the training volume of compound lifts and increase caloric intake over time. The key here is a gradual increase over the span of several training cycles. This way, the muscle soreness from sharp increases in resistance training volume will not disrupt skills training. As well, this gives time for the athlete to become acclimated to their increasing bodyweight.

There are more benefits to a high volume training phase than just hypertrophy.

Increased muscle coordination via repetition volume

Re-sensitization to high-intensity training

Muscular endurance and work capacity

Pair this with proper fueling and let hypertrophy be a by-product.

Question #3 - How would you start with plyometrics for a fighter that’s never done plyometric training before?

For lower body plyometrics like jumps and hops, start with “extensive” plyometrics. Also known as low level plyometrics. Simple exercises like plyometric pogo hops can be prescribed to help the fighter familiarize themselves with redirecting energy/force before moving onto more intensive plyometrics like depth jumps and lateral bounding.

Because extensive/low-level plyometrics are lower impact, they can be trained with relatively high volumes which in turn, will develop favourable tendon and muscle properties that will aid in getting the most out of intensive plyometrics.

For the upper body, exercises like assisted plyometric push ups as well as continuous medicine ball slams are a good choice.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Training Session Structure, Single Leg Explosiveness and High/Low Training - Combat Sports S&C Q&A #1

This week’s questions and answers session covers topics such as training session structure, single leg training for power and explosiveness as well as high/low training categorization.

These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is your philosophy on the structuring of a training session?

The overarching goal behind structuring a training session is to optimize the training adaptations from each exercise within the given session.

First things first, any strength and conditioning training session for a combat sport athlete will start off with a warm-up. I utilize a “RAMP” warm up, the main goal is to raise body temperature, activate muscles, mobilize the joints and potentiate the athlete’s neuromuscular system system to reach the intensities seen in the training session.

The second order of training involves performing exercises that have require a high neuromuscular demand. These are usually high-velocity or high-force output exercises like plyometric jumps and medicine ball slams or heavy compound lifts. The reason why these are performed first is because these training modalities are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigued. In other words, athletes will not be able to reap in the benefits of plyometric and max-strength training if those exercises are placed near the end of the session.

Followed by this, are accessory exercises that are single-jointed or aimed at smaller muscle groups. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Conditioning, depending on the type, will usually be placed at the end of the session.

Here is an example of a full body MMA workout (performed descending order) following these training session structure principles:

RAMP Warm Up (Mobility flow, FRC, Core training, Bodyweight Jumps)

DB Weighted Plyometric Jump

Plyometric Push-Ups

Banded Zercher Squats

Barbell Overhead Press

Cossack Squats + Rotating Lower Back Extension Superset

Banded Rear Delt Flies + Bicep Curl Superset

Aerobic Power Intervals

Cooldown

There are some nuances to structuring a training session however, especially if you’re using methods like post-activation-potentiation or if you’re prioritizing certain power, strength or structural training qualities. I’ve written an in-depth article “Exercise Order - Principle for Sequencing A Training Session”. In this article, I also detail the principles of fatigability and prioritization to help you navigate training session programming. Check it out.

Question #2 - How do you develop single leg or staggered stance explosivity?

Single leg power is first built on a base of bilateral strength and unilateral stability. Before chasing power and explosivity in split or staggered stance movements, ensure that you have spent time building up your strength through squat, deadlift and split squat variations.

Moving forward, some of my favorite exercises for combat sport athletes include lateral bounding exercises, staggered stance kettlebell swings and staggered stance trapbar deadlifts (links included).

The reason I prefer these exercises is because of their ability to transfer over to both striking and grappling performance.

Lateral bounding variations develops lower body power in a way that compliments the in-and-out and angle changing agility demands of striking sports.

Staggered stance variations like kettlebell swings and trapbar deadlifts develops all of the strength and power qualities similar to it’s even-stance counterpart but puts extra emphasis on the back leg. By overloading the back foot and hip, it can possibly enhance force production in back-foot-driven grappling and striking movements such as shooting the double leg takedown or the power-straight and rear power-kick.

Question #3 - What happens if MMA workouts fall in between the high/low categorization of training you’re talking about in ebook?

Many training sessions or training days in reality will fall in between high and low. When this happens, I tend to side on the conservative side and count them as high.

The high/low categorization I mention in my ebook is simply a tool used to help us better understand and balance training stress throughout a training week. The important thing is to consider the training volume and intensity of each training session, the associated recovery cost, and how it will affect performance on subsequent training sessions or the next training day.

If you have a hunch a particular training session or class incurs much more stress than you originally thought, take some readiness data post-training and track fatigue markers like muscle soreness or nervous system readiness through jump or grip testing.

Remember, nothing in the chaotic world of combat sports training is set in stone. It’s great to have a framework to guide you, but this does not replace trial and error and constant refining of the training and planning process.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports

My latest guest post on Fight Camp Conditioning covers the complexities of developing conditioning in the world of combat sports.

The training industry has come a long way since the time when tire flips and sledgehammer tire slams were the gold-standard for building endurance in MMA. As the sport becomes more popular and the quality of education for trainers improve, the way we approach conditioning should also improve. In the modern industry, it’s now about air-dyne assault bikes, mobility flows, perfectly crafted work-to-rest ratios and the use of heart rate tracking technology.

While there is nothing flawed with the current methods, I want to take a step back, revisit the components that make up conditioning performance in the world of combat sports and consider the application of these methods. My goal is to equip coaches, especially new coaches entering in the world of combat sports, with the knowledge needed to tackle the complexities that these combat sports possess.

Read More on the Fight Camp Conditioning Website

[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Plyometric Push-Ups and Progressions for Power Development

Push-ups are one of the most commonly used exercises among fitness buffs and elite-level athletes. As a closed-chained exercise that targets the chest and upper body musculature, push-ups are highly effective for improving upper body pushing strength and endurance, and can be done with no equipment.

Push-ups are one of the most commonly used exercises among fitness buffs and elite-level athletes. As a closed-chained exercise that targets the chest and upper body musculature, push-ups are highly effective for improving upper body pushing strength and endurance, and can be done with no equipment. There are plenty of regressions, progressions, and variations to pick from, making push-ups useful for athletes of all types. From bodyweight push-ups to loaded isometric push-ups, there are also various ways to load and challenge the movement...

[Read More @ SimpliFaster.com - Click Here For The Link]

The Science of Core Training: Training Methods & Application (Part 2 of Core Training Series)

Part 2 of this core stiffness article series will cover the core training principles and methods that drive short and long-term improvements in performance.

Read Part 1 Here

In part 1, I went over what the core is and the function of core stiffness in relation to sporting performance and optimal force and power output. To recap: core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed.

Highly recommend reading part 1 before continuing on with this article.

In part 1, I mentioned that improving performance via increased core stiffness will depend on multiple variables:

The nature of the sport and the energy systems involved (How long is the core braced for? Does the athlete need more strength? Or more endurance?)

The particular movement you're trying to improve by increasing core stiffness

The properties of the movement itself and the speed of core stiffening

The magnitude of core stiffening (stiffer doesn't always mean better, remember: fast and powerful athletes also need to learn how to relax at the right times - like the example of the punches and kicks we used earlier).

First off, I'd like to break this article up into 2 categories, short-term improvements in core stiffness and long-term improvements in core stiffness.

SHORT-TERM IMPROVEMENTS

Short-term improvements or increases in core stiffness, are characterized by improvements seen within the same training session. Known and performed as "core activation" drills among personal training circles, some claim that performing core exercises prior to the main exercises of a workout "wakes up" the core and improves performance on the subsequent exercises. While terms like "wake up" are very arbitrary, it helps to look a potential mechanism by which core activation drills help with short term performance.

Post Activation Potential

Benjamin Lee and Stuart McGill carried out a study in 2017 to measure the effects of short-term isometric training on core torso stiffness and found beneficial results. For the core isometric training protocol, participants performed the plank, side plank and bird dog exercises for 5 sets of 10 seconds - with coaching cues being offered and standardized to all participants. Using both passive and active torso bending trials, the results showed that most participants had reductions in torso deflection and increased core stiffness (more details here).

While this study showed that short-term core stiffness can be increased via isometric core exercises, it doesn't tell us how that core stiffness will transfer to performance in other exercises, or how long this effect lasts. In their discussion, the authors pointed to the fact that the isometric exercises done could have elicited a post activation potential (PAP).

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where strength and rate of force development (power) is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. The most common protocols may include heavy back squats to elicit a PAP effect before sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses before performing ballistic medicine ball pushes/throws. Utilizing the PAP effect is also known as complex training. Here are some examples of exercise pairings, from the NSCA.

Taken from https://www.nsca.com/Education/Articles/Hot-Topic-Post-Activation-Potentiation-%28PAP%29/

For a concise explanation of the potential mechanisms behind PAP and how it works, visit Science For Sport.

Back to the study. While the authors pointed out the PAP mechanism, they acknowledged that their core training protocol, despite improving core stiffness, did not meet the requirements of a "potentiating exercise". In a standard PAP protocol, the potentiating exercise has to be close to max effort, with the recovery time reflecting the nature of exercise. Lee & McGill's (2017) study's core training protocol included 5 sets of non-fatiguing core exercises (only 10 seconds long - bodyweight, no added resistance), so I'd be interested to see if there could be a larger PAP effect if some core exercises are taken to near max effort. Here are some ideas:

Complex Training For Core & Power Exercises

Weighted Planks into Medicine Ball Slams (2-3 minute recovery)

(3-6 complex sets of <30sec weighted planks into 4-8 max effort slams)

Planks are one of the most frequently prescribed core exercises in the fitness and strength training. An easy way to increase the difficulty of the plank is to add extra resistance - perform them weighted. In this complex set, the weighted planks act as the potentiating exercise, increasing the the power output of the slams. While the effort should still be high during the planks, the physiological stress is relatively low compared to for example, a set of heavy front squats; meaning the recovery time should be lower than most heavy compound movements. A recovery time of 2 minutes should be adequate before performing the medicine ball slams.

Squatted Pallof Press Into Rotational Medicine Ball Slams/Throws (1-2 minute recovery)

(3-6 complex sets of 6-8 presses into 4-8 max effort slams/throws)

In this example, I use an anti-rotation exercise to potentiate a ballistic exercise for better power transfer. I also added a small rotation component to what would normally be an anti-rotation exercise (the pallof press) to mimic some of the movements seen in the medicine ball rotation throw. Keep in mind, I still maintain tension on my obliques working and the shoulder girdle stable during the press out and rotation. Recovery time can be anywhere from 1 to 2 minutes.

Other Potential Ideas

Core Stiffness For Powerlifting

Aside from using higher effort complex sets, I have found situations where non-fatiguing core exercises can help improve the quality of a training session. For the last couple of months, I've been using bodyweight planks and shorter weighted plank sets with my powerlifters prior to the main compound lifts . Planks are a good way to emphasize whole body tension (a skill that is required for powerlifting success), to improve the lifters' perception on how active their core for the rest of the training session, and to remind them about the importance of a rigid torso during the powerlifts. Most, if not all of my powerlifters, have found this pre-lifting core work beneficial.

With this protocol, perform several sets of planks at a low RPE (non-fatiguing) to avoid overly fatiguing the core musculature before the compound lifts. More advanced trainees can experiment with planks at higher intensities to elicit a greater PAP response. Slowly increase the intensity of these planks over time to find the sweet spot (balance of volume and intensity).

Core Stiffness For Weightlifting

Another idea I've implemented in the past is the use of higher velocity core stiffening drills to help facilitate weightlifting technique improvements. The catch position of snatches and cleans require a lifter to quickly decelerate the weight by using the prime movers and stiffening the core upon bar contact. I've found depth drop landings or plyometric regression exercises to help with this. Here's a quick example with one of my Strongman/Powerlifting athletes, who was brand new to the Olympic lifts at the time. Used in conjunction with other coaching techniques, he made some good improvements just over the span of 3 months.

Intra-abdominal Pressure (IAP)

If you've spent anytime studying strength training or have spent time in the weight room, you probably heard of the concept of intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). Also referred to as "bracing", intra-abdominal pressure is a technique by which a trainee creates 360 degree pressure in the abdominal cavity through controlled inhalation. The created pressure helps stabilize the lumbar spine, reduce the risk of back injuries as well as improve force output. The concepts of core stiffening and creating intra-abdominal pressure are complimentary and much like the core stiffening concepts discussed previously, IAP is not an all or nothing phenomenon.

IAP happens on a continuum, and can vary in intensity and duration depending on the movement requirements of the task. Coaches around the world all stress the idea of creating IAP during strength training, however, not many of them can explain it as well as Chris Duffin (Kabuki Strength) and Stuart McGill. Kabuki Strength describes IAP as a continuum of respiration (breathing) and stabilization (max effort IAP), best represented by a dial.

To give an example, the lumbar stability needs during a 1RM compound lift is different than a sub-maximal activity like running. Running requires just enough IAP to stabilize the torso, while still allowing for optimal breathing. Turn the knob accordingly.

““Improving your ability to select and coordinate the correct dial setting is the key for fluid movement and higher performance in any activity””

long-term improvements

Long-term improvements in core stiffness are characterized by improvements seen over weeks and months of core training. This section will cover the different categories of core training, as well as general training principles that drive long term improvements.

Core Training Categorization

To start, it's best to differentiate between core exercises in order to better analyze their cost-to-benefit ratio. All exercises fall on a general to specific continuum, with the reference points being the movement you want to improve, or the sport/position you're playing - core exercises are no different. Dedicated core exercises can be broken down into several categories:

1. Isometric Core Exercises

Isometric exercises are exercises where force is produced without a change in muscle length. Exercises like planks and hanging L-Sit where you're maintaining your body position are examples of isometric core exercises.

2. Anti-Rotational Core Exercises

Anti-Rotational exercises also fall the "isometric" category. These exercises challenge your ability to stabilize your body to prevent from rotating to any one side, maintaining your body position against an external force or in an imbalanced position. Common exercises include the pallof press, shoulder taps in push up position and many exercises in the half kneeling position. Other great examples not many people know about could be suitcase deadlifts, and uneven farmers walks (videos below).

3. Isotonic Core Exercises (Sagital Plane/Transvere Plane)

Isotonic exercises are exercises that consist of an eccentric and concentric portion - exercises that are not isometric (holds). They can be further broken down into sagital/transverse plane exercises. Sagital plane exercises include standing cable crunches, sit ups and hanging leg raises, while transverse plane exercises involves any exercise that involve torso rotation like cable wood-choppers and medicine ball russian twists.

4. Ballistic and Plyometric Core Exercises

Ballistic exercises are concentric-dominant power movements with little to no eccentric muscle action, such as jump squats and explosive push ups. In the realm of core exercises, medicine ball slams, rotational throws can be considered ballistic, but keep in mind the prime movers such as the shoulders and glutes also contribute to the force output.

Plyometric exercises are exercises with a short eccentric-concentric turnover, using the elastic properties of our muscles to improve speed and repeated power output. Many movements like running, repeated jumps/hops and combination striking (in martial arts) are considered plyometric. There are also plyometric exercises designed just to target the core musculature - many of these being rotational. I've posted a few examples below:

Taken from Nick Curson (Speed of Sport)

Taken from Elliot Hulse

Training principles and methods To Improve Performance

Conversations usually go south whenever the topic of "transfer to performance" is brought up; there are many complex variables to take into consideration and everyone seems to have their own definition of "functional" or what exercises will and will not help improve performance. I'll be giving some general tips and training principles of core training that can be applied to various different sports.

Post-activation-potentiation, non-fatiguing core primers and intra-abdominal pressure are all acute techniques that CAN lead to long-term improvements

The research is still not conclusive on whether these are significantly beneficial, but in theory: accumulating small short-term improvements should lead to long term improvements in performance. In other words, if these techniques are performed consistently throughout your training program, they may add up to a measurable increase in strength, power and endurance (whatever you're aiming for). I would also add that the use of PAP and core primers are optional, but in my opinion, IAP is not. I consider IAP a skill that must be learned and utilized consistently in order to effectively produce force, and stay safe doing so.

A combination of general and specific core exercises should be performed

Don't fall into the "functional" trap of prescribing overly-specific exercises. A general exercise that does not fully mimic the movement you're trying to improve can still be beneficial. For example, weighted planks are a great general core exercise to build core strength and endurance that will transfer over to various movements. Once a good base is built, you can start experimenting with more specific exercises. I've included some examples of specific exercises at the end of this article, mainly geared towards improving punch power, but can also be used as core training.

To learn more about the general-specific continuum and how to classify exercises for better training prescription, read my article I wrote on training variation here.

Principle of progressive overload

This is the premise behind improving any type of performance measure. Progressive overloading your core exercises either through a change in position, adding extra resistance, increasing the volume via sets, reps or time. In order to improve, you must progressively add stress to your physiological system, recover from it, and come back stronger.

Improving Core Strength (Slow-Isometric Stiffness)

Core strength, or slower-isometric type core stiffness, is primarily built using isometric and anti-rotation based exercises. Almost every core exercise listed above can be used to improve core strength, but what differentiates training core strength from core endurance is the intensity at which these exercises are performed. Reps should be done in the lower rep range (~<6 reps per set) or 80-95% of 1RM if a 1RM is applicable. Accordingly, intensity/weight progression is what you should be focused on. For example, progressively working towards heavier weighted planks (increasing intensity) instead of increasing the time of which you hold body-weight planks. Improving core strength will benefit every athlete, but strength and power athletes will see the best results.

Improving Core Ballistic/Plyometric/Power Ability (Fast-Recruiment Stiffness)

Core plyometric ability, or what I like to describe as a faster-recruitment type core stiffness, is built through plyometric core exercises and have a higher skill/timing component to it. This is the type of core stiffness I discussed in part 1, that is required for high-impact athletes who perform punching, kicking and striking movements. The ability to contract-relax-contract and produce a fast eccentric-concentric turnover is what defines an athlete with good core power and plyometric ability - both deceleration and acceleration are taken into account.

I gave examples of relatively advanced plyometric core training above (see Nick Curson and Elliot Hulse's videos). A more beginner friendly way to perform these exercises would be to reduce the range of motion on the exercises and reduce the power output until you improve your timing. A drill I found useful are short plyometric medicine ball rotation slams - timing and rhythm are paramount here so develop them before moving onto higher-intensity, higher-effort plyometrics.

Improving Core Endurance

When people think of the word "endurance" they immediately associate that with a low-intensity, long duration training protocol. Don't make the same mistake. Endurance can refer to the ability to maintain a certain power output for an extended period of time OR be able to repeatedly perform high-intensity bouts with little to no drop off in power output from start to finish. I recommend using work-to-rest ratios with your core exercises based on the energy system you want to develop.

Do you want to be able to repeat maximal high-intensity efforts? Use work rest ratios anywhere from 1:20 to 1:30+. For example, 6 seconds of maximum effort tornado ball slams with 2 minutes of complete rest in between sets, for several sets (1:20 work-rest ratio).

Looking to improve anaerobic capacity? Use work-rest ratios around 1:1. For example, 60 seconds of moderately heavy farmers walks with 60 seconds of active rest in between sets (1:1 work-rest ratio).

Looking for longer duration core endurance? Perform lower intensity core exercises for a total of 3 minutes+ at a time with a work-rest ratio of ~2:1. For example, hold a bodyweight plank for sets of 3 minutes with 1.5 minute rests in between. To add some variation to these longer sets, you can also perform 3-4 different core exercises as a circuit for 1 minute each. Over time, increase the duration of each set or the total number of sets (volume load progression at a set intensity).

Using work-to-rest ratios is another tool by which you can use to look at and utilize core training with. It can help you visualize which energy systems are at play, so you can make the adaptations you want to see. Endurance is specific.

Diminishing Returns

More core work means better performance right? Not so fast. Welcome to the principle of diminishing returns. The more you train core stiffness, the less benefits you reap in. I see core stiffness training a lot like maximal strength for sports. There comes a point where more core training does not equate to better performance on the field, court, platform or ring. Core stiffness, much like strength, serves as a foundation on which other important physical attributes are built on - rate of force development, agility, resilience to injury to name a few. Be careful not to allocate all of your time and energy into core stiffness training, while neglecting the development of other skills and attributes.

So how much is enough?

Unfortunately, I don't have a concrete answer for you. This really depends on what sport and movement patterns you're referring to. Core training should fill the gaps of your physical development, and be used in conjunction with sport-specific skill work and strength/power/plyometric training. Being able to competently perform all the movement patterns and core exercise categories listed above is a great start.

Biggest takeaway

If there's one thing you take away from this article, it's that core stiffness training is context-specific and should be thoughtfully prescribed and developed. Core training does not have to be boring, so don't be afraid to get creative. Below is some of my content I've put out on core training, core ballistic training and various medicine ball slam exercises. Thanks for reading!

ARTICLE: Great Core Exercises You're Not Doing

CORE TRAINING VIDEOS:

The Science of Core Training: Core Stiffness & Performance Overview (Part 1 of Core Training Series)

This article will overview the concept of core stiffness and how it's applied to several sporting performances and movements. Core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed.

Core training has been all the hype the last several years - from an aesthetic point of view (achieving 6 pack abs) to it's potential role in reducing lower back pain and related symptoms. This article won't be touching on any of those points. I'm speaking more from a performance-enhancement perspective, specifically, the role of core stiffness and it's relation to performance outcomes.

What is the "core"?

The musculature and structures between your shoulder girdle and your hip; the superficial and deep abdominal muscles.

What is the function of the "core" and what is "core stiffness"?

Ask a performance coach and they'll give you one answer. Ask a physical therapist and they might give you a different one. From a physical therapy or rehabilitation setting, core stiffness may refer to increased muscle tone that leads to lower back pain and movement restrictions. In the performance sports setting, core stiffness may refer to the core's ability to maintain stability in response to the influence of external forces, which may vary in magnitude, direction and speed. For the purpose of this write up, I'll be talking about the latter.

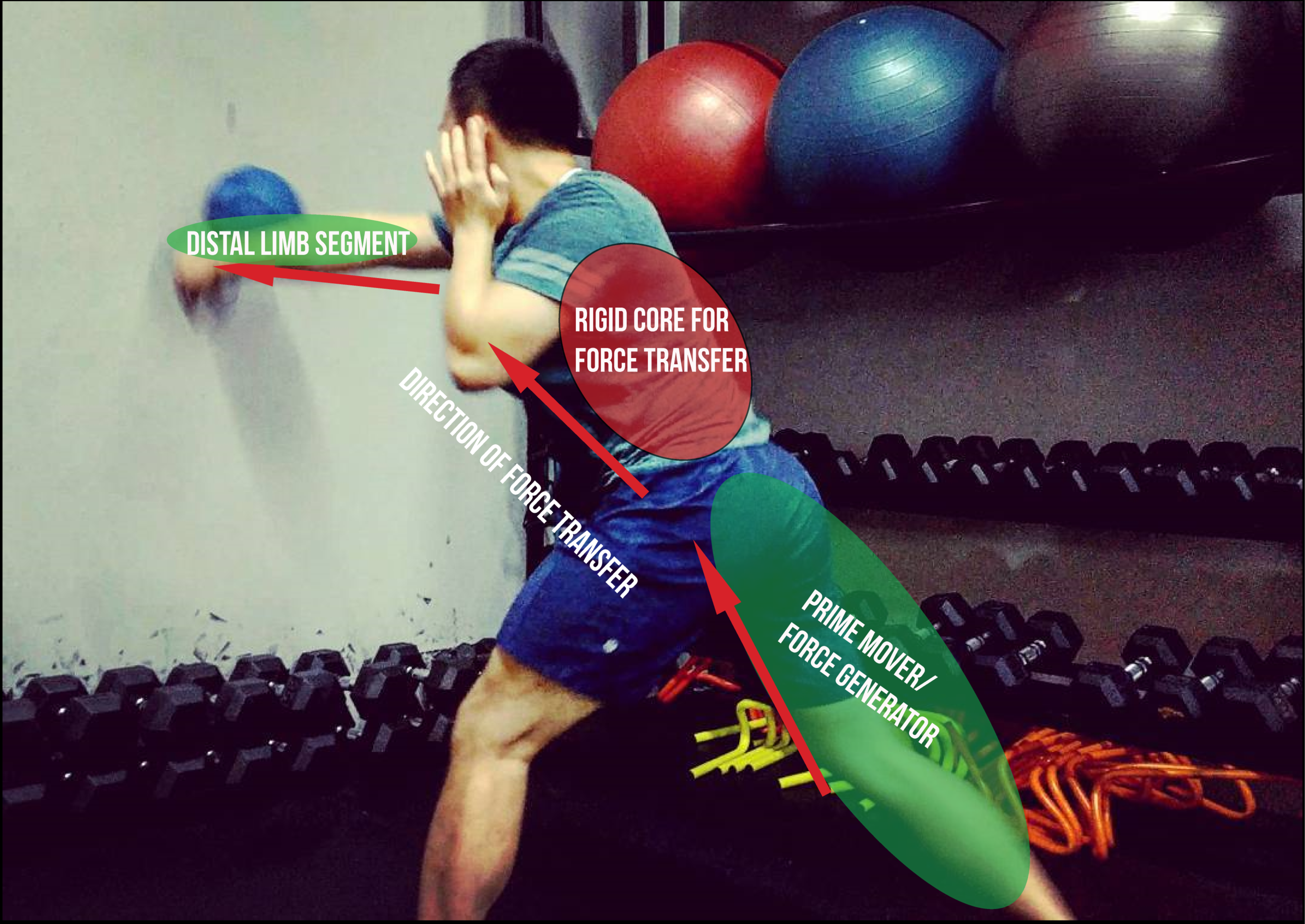

To my knowledge, the function of the core is to transmit force, prevent force/power leaks and maintain the position of certain joints and body segments. In the words of professional lower back and spine expert Stuart McGill, he describes the function of the core to "stiffen the torso to prevent motion, [and] enhance motion of the distal limb segments".

In the majority of sporting performances, the ability to accelerate distal limbs is the key to high power output: think about throwing a baseball, kicking a soccer ball, jumping, pushing, punching. Stiffening the torso to prevent excessive motion and enhances force production and power output because it acts as a medium for force transmission - ensuring all the force you generated is directed towards your intended direction. A floppy and weak midsection results in a weak kick, a weak throw, a weak jump and a weak landing.

an overview, with examples.

The idea of core stiffness allowing for better force production/transfer can be applied to many different scenarios. I'll give 3 examples from 3 different sporting types, a mixed sport (Mixed martial arts/combat sports), an endurance-dominant sport (Cycling) and a strength-dominant sport (Powerlifting).

In each example, the RED highlighted area represents the "core": the superficial abdominal muscles (rectus abdominis), the deeper muscles like the transverse abdominis as well as surround muscles like the obliques (for rotation), latissimus dorsi and rotator cuff muscles.

The GREEN highlighted areas represent the prime movers that are responsible for generating force through concentric muscle action, and/or the distal limb segments that are used to transmit force into the intended direction or to move a certain object.

Example #1 - The Punch and Kick in Martial Arts

The straight right/left punch is one of the most basic, yet intricate techniques in martial arts. Contrary to what many think, the prime movers of the straight punch are actually the back leg, the muscles surrounding the hip and the shoulder girdle, NOT the arms. Power is generated by pushing off the back foot, contracting the glute, and directing that force into the distal limb segment (which is the fist in this scenario).

In order to effectively transmit that power from foot to fist, the core must rigid. The obliques must create enough deceleration force to prevent your torso from over-rotating (shifting you off balance), and your shoulder girdle must be sturdy enough so loosen up on impact. Additional, these types of movements (punches, kicks, hitting/impact-movements) exhibit a "double peak" in regards to muscle activity (measured through Electromyography (EMG)). In other words, whenever performing a powerful movement, the muscles will go through 3 phases: contract/stiffen, relax, and contract/stiffen once again upon impact, showing a "double" peak in activation (will be pictured below).

Stuart McGill et al. performed a study in 2010 on elite mixed martial artists (Georges St. Pierre, David Loiseau to name a few) that introduced me to this concept so I'm sure he can explain it more clearly:

“Many of the

strikes intend to create fast motion and finish with a very large

striking force, demonstrating a ‘‘double peak’’ of muscle activity.

An initial peak was timed with the initiation of motion

presumably to enhance stiffness and stability through the body

before motion. This appeared to create an inertial mass in the

large ‘‘core’’ for limb muscles to ‘‘pry’’ against to initiate limb

motion. Then, some muscles underwent a relaxation phase as

speed of limb motion increased. A second peak was observed

upon contact with the opponent (heavy bag). It was postulated

that this would increase stiffness through the body linkage,

resulting in a higher effective mass behind the strike and likely

a higher strike force.”

To further illustrate the "double peak" in activation, and to tie it back to the discussion earlier about prime movers and the core, here's a figure taken from McGill et al's 2010 study (green and red highlights made by myself).

This figure illustrates the muscle activation of the left back muscles during a left leg kick to a heavy bag.

Taken from McGill et al. 2010

#1 in green represents the initial activation of the muscle (phase 1 - contraction), where the foot pushes off the floor and the hip flexors and obliques contract in order for the leg to be lifted into the air. The prime movers are the hip, quadriceps and left back.

#2 in red represents the relaxation phase (phase 2) where the leg is in mid air and force is being transmitted through the core, to hit the intended target (shin/foot hitting the heavy bag).

#3 in green represents the second activation of the muscle (phase 3 - contraction again), where the muscles stiffen up once again on impact.

An athlete with a weak core, or an inability to stiffen up the core will experience power leaks in #2, which subsequently results in a lower striking force upon impact in #3.

Optimal force and power production happens when an athlete has:

Good body positioning

The ability to show double activation during strikes/impact movements

The ability to efficiently cycle through contract-relax-contract muscle action if repeated punches/kicks/impacts are performed

Strong and resilient core musculature.

Example #2 - cycling

Operating at up to 300RPM (revolutions per minute) and putting out up to 2,200 watts, track cyclists are known for their lower limb strength and power, as well as their ability to maintain extremely high power outputs for extended periods of time.

Watch the video below, notice the rigid and stable core - supported by the shoulders and arms, and how that translates to incredibly fast distal limb segment movement (in this case, the feet).

Yes, the thigh musculature are still the primary movers, but the core/torso also contribute greatly, acting like a shock absorber to negate most of the horizontal and vertical bodyweight shifting that happens during high RPMs. A strong core ensures as much of the force generated by the prime movers can be directed towards spinning the pedal.

Picture taken from TeamNater (Youtube), editted by myself.

The principles of contract-relax-contract discussed above also apply to this example. The quadricep has to relax while the hamstring is active during the (pedal) upstroke, and vice versa during the downstroke. Pair it with the fact that this is all happening at 150, 200, 250+ RPM and you'll realize the amount of motor control needed to be an elite cyclist.

Example #3 - Powerlifting

Our last example is a strength sport - powerlifting. Powerlifting is a maximal strength sport, meaning the velocity of distal limbs and the velocity of the bar is relatively low compared to other sports such as Olympic Lifting or various throwing sports. As a result, core stiffness plays a slightly different role - a slower isometric role. Although there is no contract-relax-contract cycle in powerlifting, the core still acts as a stopper for potential force leakages. The main role of the having a rigid torso/core is to support the lumbar and thoracic spine under heavy load.

In a sport where limb length and leverages are highly influential on performance outcomes, a lifter must maintain the position of their lumbar and thoracic spine so that their chest does not collapse under the weight, and their lower back doesn't go into excessive flexion. Losing position means the lifter will not be able to lift the weight up, regardless of how strong their prime movers are.

Below is an example of one of the lifters on my Powerlifting team, Amos So, bracing for a squat at a local powerlifting meet.

Context Specific

Throughout the article, I've used terms like "stable", "rigid", "strong" and "resilient" to describe the properties of a well-functioning core. Different coaches and trainers will use different terms to describe the core, so terminology is sometimes confusing.

However, what matters is how you apply these principles to your own training, or the training of your clients and athletes. Improving performance measures via increased core stiffness will depend on several things:

The nature of the sport and the energy systems involved (How long is the core braced for? Does the athlete need more strength? Or more endurance?)

The particular movement you're trying to improve by increasing core stiffness

The properties of the movement itself and the speed of core stiffening

The magnitude of core stiffening (stiffer doesn't always mean better, remember: fast and powerful athletes also need to learn how to relax at the right times - like the example of the punches and kicks we used earlier).

Much like the development of max strength for athletic performance, there are also most likely diminishing returns, so don't fall into the trap of "more core training = higher performance".

In part 2 of this series, I'll be explaining the different methods to improve core stiffness in the short-term and in the long-term.

Read Part 2 Here.

Thanks for reading, feel free to share this article with your peers and fellow coaches. Also, please check out my social media links and reach out to me if you have any questions or suggestions.

MMA Strength & Conditioning - Experts ROUNDTABLE

With the pride, fame, and money that comes with prize-fighting, it's extremely important for strength and conditioning coaches to ensure the fighters are in top physical condition come fight night - the fighters' health depend on it.Strength and conditioning work must be balanced with martial arts skills training and psychological performance and therefore presents a complex problem for performance coaches to solve. Luckily there are professionals in the field to do just that - create strong and healthy athletes to elevate the sport of MMA.

Mixed martial arts (MMA) is one of the newest professional sports around and has been gaining a lot of popularity over the last two decades. With the pride, fame, and money that comes with prize-fighting, it's extremely important for strength and conditioning coaches to ensure the fighters are in top physical condition come fight night - the fighters' health depend on it.

Strength and conditioning work must be balanced with martial arts skills training and psychological performance and therefore presents a complex problem for performance coaches to solve. Luckily there are professionals in the field to do just that - create strong and healthy athletes to elevate the sport of MMA.

Before we start, I'd like to give a special thanks to all the coaches that spent time to contribute to this article. Thank you PJ, Phil, Carmen, Danny and Dr. Galpin. My goal was to reach out to coaches from different areas of expertise to compile a list of performance tips to help both the fitness and MMA community become more educated on the physical preparation process. Enjoy!

Geoff's Commentary: PJ Nestler will be starting this article off by dispelling the myths about strength training in the sport of MMA and how strength training can set the foundation for other physical attributes.

PJ Nestler