Alternatives to Olympic Weightlifting For Power Development

Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

This is a guest post written by Vancouver-based personal trainer and S&C coach Jason Lau of Performance Purpose. Olympic weightlifting movements in the S&C environment is a controversial topic because some coaches are quite dogmatic about it’s use in power development. There are pros and cons to using them, depending on the context. Coach Jason lays out reasons to use alternatives and in what situations they would be best utilized.

Olympic Weightlifting for S&C

Olympic Weightlifting is a sport in which athletes attempt to lift a maximum weight overhead using the two competition lifts: Snatch and Clean & Jerk. These competition lifts and their derivatives: hang snatch/clean, push press, snatch/clean pulls, power clean/snatch/jerk, can often be seen programmed outside of the sport, in an athlete’s strength and conditioning program.

Due to the identical triple extension movement pattern (extension of ankles, knees and hips), seen commonly in weightlifting and sports, an athlete training the weightlifting movements can greatly improve the transfer of power from feet through torso to hands, as well as athletic coordination. In that sense, weightlifting can serve as a specific preparatory exercise that matches the high force and high velocity seen in sport that traditional heavy lifting cannot satisfy.

To quote Cal Dietz – “In order for an athlete to become fast, they must train fast.”

Then Why Use Alternatives?

Despite the power development that the weightlifting movements provides for athletes, there are also risks that you will have to consider as well.

Aside from aggravated joints such as knees, shoulders and hips, the lifts requires a high technical demand to perform correctly and safely. Time is required to master the technical aspect of the lifts. Time that should not be carelessly managed when an athlete is training for an upcoming game or season. Another factor to consider is the amount of training experience the athlete has in the weight-room. Mobility and injury restrictions may also interfere with the athlete’s ability in performing the lifts. Lack of ankle and overhead mobility and stability are restrictions are common and should be addressed before progressively overloading as it may lead to injury down the road.

Power development is also specific. In the world of S&C, specificity is king as game/competition date draws close. Does the athlete have to move heavy external or light loads within the sport? This will determine what type of loading scheme and stimulus is required. For example, a football linebacker will lean towards higher intensity hang cleans including prioritisation of strength due to the demands of their sport. On the other hand, the intensities a volleyball athlete’s program would see lighter intensities as external load is not needed to the same degree within the sport.

By taking into consideration of the limitations listed previously, alternatives can be performed and taught with relative ease while mimicking the classic lifts in velocity and movement pattern. Through alternatives, we can achieve the same stimulus that weightlifting movements bring while still improving strength in high-velocities.

Alternative Exercises

Trap Bar Jumps – Trap Bar Jumps is one of the go-to replacements for weightlifting. A previous study done by Timothy J. Suchomel indicates that when utilizing lighter loads (<40% of 1RM), the jumps displayed higher force output compared to a hang power clean at the same load. The learning curve of this exercise is relatively low where the majority of athletes can perform without difficulty while staying true to the natural movement pattern of jumping. With the versatility of the trap bar jump, it can be performed with a counter-movement while loaded with bands or weights.

Squat Jumps – Squat Jumps is a great transition towards power as an athlete is transferring out of their strength focused block. Aside from a smooth transition, a squat jump replicates the second pull during a clean. This can be performed from a quarter squat depth or full squat depth, all dependent on the athlete’s goals. Considering this exercise utilizes the squat movement pattern, it is different from an athlete’s natural jumping form so it may not satisfy the need of specificity.

Medicine Ball Toss – The med ball toss is a great exercise to have within one’s arsenal. Ballistics are predominantly concentric in nature allowing the athlete to focus on the acceleration phase without having to catch or decelerate at the end. The ability to reap the benefits of fast twitch muscle fibre contractions without the negative effects of eccentric forces can benefit the athlete. Tosses can be expressed throughout multiple planes of motion as well, not only vertically, that is what makes this movement so versatile.

Prowler Push – The vast majority of alternatives are bilateral in nature, but with Prowler Pushes and drags, we can achieve unilateral power with little technical demand on the athlete. This allows the athlete to drive off the ground and transfer force through the torso and into the prowler with no eccentric forces. This movement is versatile and can serve as a special developmental exercise for athletes in frequent sprinting sports.

To weightlift or not to weightlift?

That is the question. My answer? It depends.

I encourage coaches to look at the bigger picture. Does the athlete have enough time to learn the technicalities of the lifts? Are the athlete’s movement patterns proficient enough? Does the athlete have enough weight-room experience? Are there any severe mobility or stability issues that the athlete has to address beforehand? Are the alternatives sufficient for the time being? There is more than one route to achieve ideal athletic qualities. The factors that set apart good and bad S&C programs from each others are the risk to reward ratio, efficiency and specificity.

References

Suchomel, T. J., & Sole, C. J. (2017, September 1). Power-Time Curve Comparison between Weightlifting Derivatives. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5592293/

Shattock, K. (2018, February). The Use of Olympic Lifts and Their Derivatives to Enhance Athletic / Sporting Performance: A Mental Model. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322901416_The_Use_of_Olympic_Lifts_and_Their_Derivatives_to_Enhance_Athletic_Sporting_Performance_A_Mental_Model

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

JASON LAU is a Strength & Conditioning / Physical Preparation coach and owner of PERFORMANCE PURPOSE based out of Richmond, BC. His passions include coaching and refining badminton, volleyball and hockey athletes, beginner to provincial level powerlifters, return-to-play rehab and general population clientele of all ages.

He aims to offer a systematic and evidence based approach to off-season and in-season training, translating the athlete’s weight room progress towards their specialized sport. His goal is to drive improvement and progress of each individual within the field of athletic performance.

Website: https://performancepurpose.ca/

Instagram: @performancepurpose

Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session

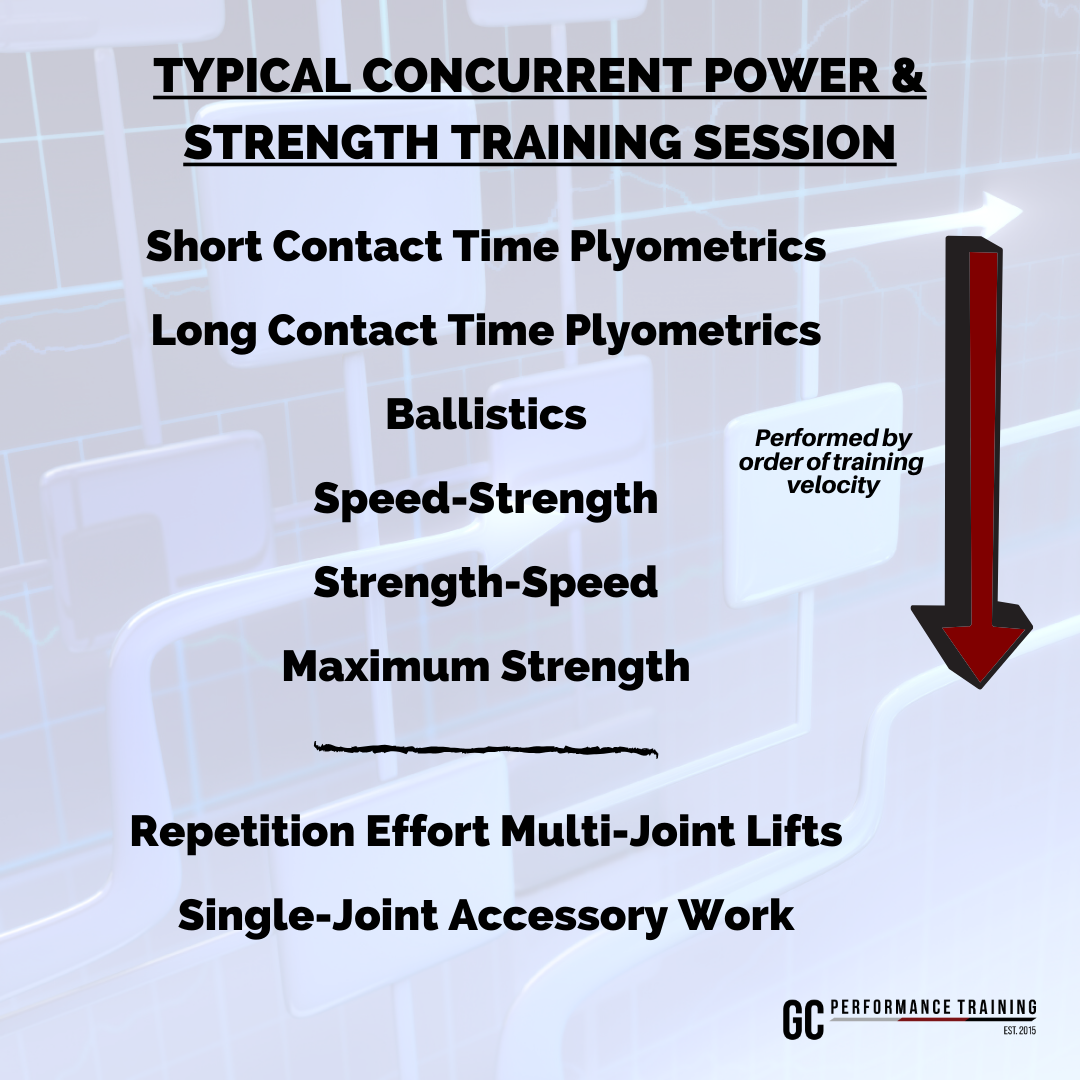

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Given that you are able to select a handful of exercises that have a good chance of influencing strength & conditioning performance measures in athletes, you must be able to sequence each training session with the exercises in the “correct” order.

I say the word “correct” very cautiously as there are no absolute truths or right or wrong in the complex, unpredictable world of human performance. To navigate through the unpredictable nature of training, it pays off greatly to have a set of principles to prescribe and coach by, while still leaving room for flexibility when new information or new prioritizations arise.

Principles for sequencing a training session

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Fatigability

The principle of fatigability accounts for each exercise modality’s sensitivity to neuromuscular fatigue. Exercises that require high nervous system output and higher physiological and psychological readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue.

One explanation for this lie in the physiological characteristics of our muscle fibers. Fast-twitch, type 2 muscle fibers possess higher contractile speeds and a higher potential to produce contractile force. For this reason, they are favored during exercises that demand high-velocities and high-force outputs. Type 1 muscle fibers in contrast, are more resistant to fatigue due to their higher oxidative properties but as a consequence, have lower force-producing capabilities.

The larger velocity and force demands, the shorter they can be sustained for.

Following the principle of fatigability, exercises modalities like plyometrics, ballistic and maximum strength should then be performed first if they are to be trained concurrently within a training session.

Accessory exercises that are single-joint in nature, aimed at smaller muscles groups can be placed in the latter half of a training session. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Priority

The principle of priority is highly correlated to the principle of fatigue, and states that an athlete should be performing the exercises that are most important to their primary training goal, at a time when they have the most resources to do so. From an energetic and fatigue standpoint, this usually means the beginning of a training session when the athletes are at their highest point of psychological and physiological readiness (after a proper warm-up of course).

Not including the athletes at the ends of the endurance-strength spectrum (like endurance cyclists and powerlifters) the primary goal of many athletes is to develop higher rate of force development (RFD) / power and transfer this improved athleticism to sport-specific skills. Strength training is a secondary goal but must also be considered as it is crucial for second order effects such as injury risk reduction, slower-velocity force production and carryover to RFD training.

If your primary goal however, is to develop maximum strength, heavy compound lifts should come before high-velocity training. This sequencing does not follow the principle of fatigability, but satisfies the principle of prioritization.

the contrast training exception

Contrast training offers an exception to the principles of fatigability and priority, where heavy compound lifts are deliberately performed first to elicit a post-activation-potentiation (PAP) effect, even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where RDF/power is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. You’ve probably seen protocols utilized by strength & conditioning coaches such as heavy back squats paired with sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses paired with ballistic medicine ball throws and slams.

While the most common form of potentiating modality is maximum strength (85-100% of 1RM or <0.5m/s bar speed if you’re using VBT), I, along with other coaches I’ve communicated with, have had success using strength-speed exercises as a potentiating modality. Exercises like weighted trapbar jumps or Olympic weightlifting variations, loaded to achieve velocities around 0.75 - 1.0m/s.

Isolating Before Integrating in Rehabilitation & Return-To-Play settings

In the context of rehabilitation, priority is given to exercises that are aimed towards rebuilding the capacity of the injured muscle, joint, tendons and/or ligaments. In my return-to-play protocols for my athletes, I will place single-joint, stability and balance-based exercises in the beginning of the training session before integrating them back into strength and plyometric exercise regressions.

Since our main goal is rebuilding the athletes’ capacities, velocities and force-outputs are not expected to be high, therefore there will be little detrimental effects to placing those exercises last.

Anecdotally, my athlete’s have reported feeling more confident in performing strength and plyometric exercises after an extended warm up and emphasis on their injured area.

Wrapping it up

Exercise sequencing should be individualized on an athlete-by-athlete basis using the principles of fatigability and priority, while taking into account special circumstances like performing advanced training protocols or managing injured athletes. While some can argue exercise selection has a larger impact influencing performance outcomes and that exercise order is of less importance, using principles for exercise sequencing bring a consistent and strategic approach to the design and implementation of a training session that cannot be overlooked by high performance athletes and coaches.

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Published on SimpliFaster.com] Individualizing and Optimizing Performance Training For Basketball](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1559464401554-UTSFUHZQUTNOISFNVX1P/Daryyl-Wong-Court.jpg)

![Tapering & Peaking: How To Design A Taper and Peak For Sports Performance [Part 2 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501283047888-1OMY4OC27GHE81P94CPG/mountains-sport-nature-human-mountain-climbing-wallpaper-hd-black-1920x1080.jpg)

![Overreaching and Overtraining [Part 1 of Peaking Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1501052506104-FOT7NYG35KYOVLK3J12R/crossfit.jpg)