Plyometric Development for Muay Thai & Kickboxing

Plyometric movements involve a pre-stretch of the muscle-tendon unit in order to create a higher rate of force development. It is crucial to develop this ability in the sport of Muay Thai and Kickboxing as many blocking, kicking and kneeing techniques are plyometric in nature.

This article to brought to you by

Geoffrey Chiu

GC Performance Training Owner & Coach

Ricardo Alvarez

Lumpinee/Rajadamnern Stadium Muay Thai Fighter

Primo FightWear

Use GCP10 at check out for 10% OFF some of the best modern training gear in the industry today.

Plyometric movements involve a pre-stretch of the muscle-tendon unit in order to create a higher rate of force development. It is crucial to develop this ability in the sport of Muay Thai and Kickboxing as many blocking, kicking and kneeing techniques are plyometric in nature.

In this article, we will use continuous plyometric kicks, that we see often in Muay Thai training, as the prime example of plyometrics in action, as well as offer several plyometric progressions you can incoporate into your strength & conditioning program to develop your speed and reactive strength on the mats and in the ring.

This article and the exercise progressions provided solely focus on developing the physical attributes required for high-level continuous kicking, blocking and more advanced, reactive-combinations.

However, it is important to keep in mind that the number one and most important step to fast and powerful kicking is technique.

Stepping in with the pivoting foot,

Whipping your leg and turning your hips

Swinging the same side arm to project the kicking leg for counter-balance.

If you've ever worked with a high-level Muay Thai or striking coach, you will have heard that "power and speed comes from balance". Balance is key.

From a physical performance lens, continuous kicking is a highly plyometric ability, and there are further improvements we can drive through S&C training outside of technical practice. The key is developing tendon stiffness in the lower leg as well as the contraction-relaxation speed of the hip flexors.

Increased tendon stiffness is an adaptation that comes from progressive plyometric training, benefiting many striking athletes as they will be able to possess faster ground contact times (faster kicks, faster blocks), increase their rate of force development, and maintain their “spring in their step” for a longer duration within a given fight.

exercise progressions

Plyometric Progression Series #1 - Plyometric Pogo Jumps performed in Bilateral Stance, Fight Stance and Switching Stances. While considered an extensive variation in the world of S&C, these are higher amplitude relative to the jumping intensity most Muay Thai athletes get from skipping rope and an ability I find that many fighters lack in Muay Thai.

Plyometric Progression Series #2 - Continuous blocks to pair a plyometric action of the lower leg with the flexion of the hips. A rudimentary stage to building the rhythm and coordination needed for continuous kicks.

Plyometric Progression Series # 3 - Alternating kicks and blocks, the last step of the progression before chaining your kicks together. The use of the block acts as a buffer to allow you to regain the rhythm and ground contact time to execute your kicks. If you're an experienced Muay Thai fighter/kickboxer with little experience in plyometric training. We recommend investing time into the extensive variations seen in Series #1 and #2 for several weeks before moving onto the last progression.

Programming Recommendations

Plyometrics, like most high neuromuscular-demand modalities of training, are best performed at beginning of the training session, after an comprehensive warm-up. To reap the biggest benefits of plyometric training, fighters should be performing these fresh and non-fatigued. For more explanations, read this article on exercise order to learn how to optimise your training sequencing.

If you’re an experienced fighter by have limited experience in plyometric training or dedicated S&C training in general, it is recommended you start by limiting your jump height and perform a higher number of repetitions.

Plyometric Pogo Jumps (Bilateral Stance, Fight Stance, Switching Stances)

Weekly Frequency: 2-3x a week

Sets x Reps: 3-4 Total Sets x 16-20 repetitions per training session

A rule of thumb on jump height for these plyometric pogo jump variations - higher than your skip rope jump height, but lower than your max effort jump. Focus on quick ground contact times and let your feet and ankles do most of the work.

Plyometric Continuous Blocks

Weekly Frequency: 2-3x a week and/or can be incorporated into Muay Thai Training

Sets x Reps: 2-3 sets each leg x 16-20 repetitions per training session

Alternating Kicks & Blocks

Weekly Frequency: Incoporated into Muay Thai training

Sets x Reps: 2-3 sets each stance x 10 repetitions or done in clusters of 3-5 repetitions

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD

Want to learn more about exercise selection for combat sports?

Chapter 7 of my Strength & Conditioning for combat sports eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

Exercise Order - Principles For Sequencing A Training Session

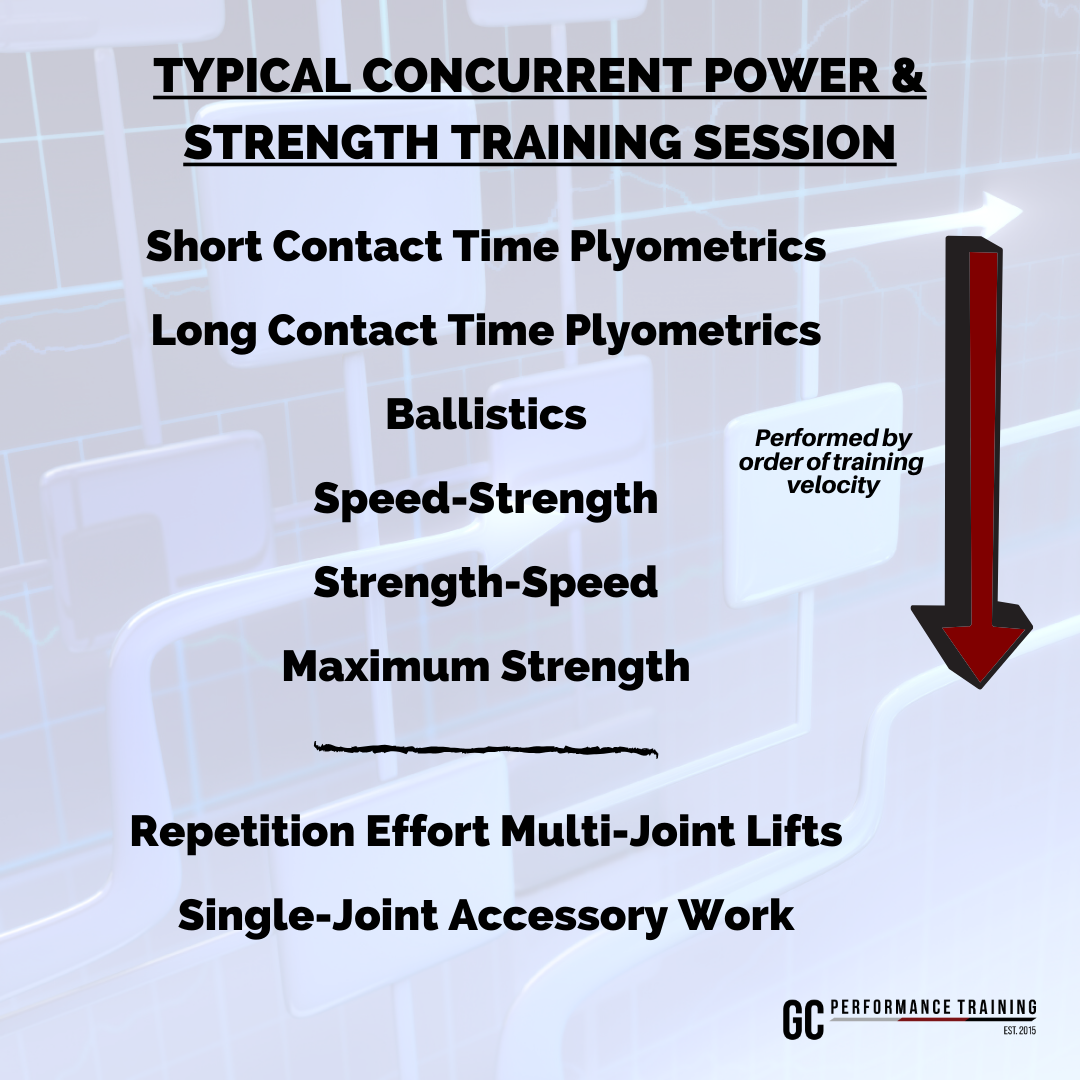

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Given that you are able to select a handful of exercises that have a good chance of influencing strength & conditioning performance measures in athletes, you must be able to sequence each training session with the exercises in the “correct” order.

I say the word “correct” very cautiously as there are no absolute truths or right or wrong in the complex, unpredictable world of human performance. To navigate through the unpredictable nature of training, it pays off greatly to have a set of principles to prescribe and coach by, while still leaving room for flexibility when new information or new prioritizations arise.

Principles for sequencing a training session

The main goal of exercise sequencing when training athletic qualities concurrently (plyometric ability, rate of force development, maximum force output, muscular endurance, etc ) is to optimize the training adaptations from each single modality and reduce the detrimental effects of neuromuscular fatigue.

Optimizing exercise order is driven by two interrelated principles: fatigability and priority.

Fatigability

The principle of fatigability accounts for each exercise modality’s sensitivity to neuromuscular fatigue. Exercises that require high nervous system output and higher physiological and psychological readiness are more susceptible to performance detriments due to fatigue.

One explanation for this lie in the physiological characteristics of our muscle fibers. Fast-twitch, type 2 muscle fibers possess higher contractile speeds and a higher potential to produce contractile force. For this reason, they are favored during exercises that demand high-velocities and high-force outputs. Type 1 muscle fibers in contrast, are more resistant to fatigue due to their higher oxidative properties but as a consequence, have lower force-producing capabilities.

The larger velocity and force demands, the shorter they can be sustained for.

Following the principle of fatigability, exercises modalities like plyometrics, ballistic and maximum strength should then be performed first if they are to be trained concurrently within a training session.

Accessory exercises that are single-joint in nature, aimed at smaller muscles groups can be placed in the latter half of a training session. Their relatively low technical and neuromuscular demands means their effectiveness will not be diminished to the same degree with the onset of fatigue.

Priority

The principle of priority is highly correlated to the principle of fatigue, and states that an athlete should be performing the exercises that are most important to their primary training goal, at a time when they have the most resources to do so. From an energetic and fatigue standpoint, this usually means the beginning of a training session when the athletes are at their highest point of psychological and physiological readiness (after a proper warm-up of course).

Not including the athletes at the ends of the endurance-strength spectrum (like endurance cyclists and powerlifters) the primary goal of many athletes is to develop higher rate of force development (RFD) / power and transfer this improved athleticism to sport-specific skills. Strength training is a secondary goal but must also be considered as it is crucial for second order effects such as injury risk reduction, slower-velocity force production and carryover to RFD training.

If your primary goal however, is to develop maximum strength, heavy compound lifts should come before high-velocity training. This sequencing does not follow the principle of fatigability, but satisfies the principle of prioritization.

the contrast training exception

Contrast training offers an exception to the principles of fatigability and priority, where heavy compound lifts are deliberately performed first to elicit a post-activation-potentiation (PAP) effect, even if RFD/power is the primary goal.

PAP is a physiological/neurological phenomenon where RDF/power is increased due to previous near-maximal muscle contractions. You’ve probably seen protocols utilized by strength & conditioning coaches such as heavy back squats paired with sprinting and jumping, or heavy presses paired with ballistic medicine ball throws and slams.

While the most common form of potentiating modality is maximum strength (85-100% of 1RM or <0.5m/s bar speed if you’re using VBT), I, along with other coaches I’ve communicated with, have had success using strength-speed exercises as a potentiating modality. Exercises like weighted trapbar jumps or Olympic weightlifting variations, loaded to achieve velocities around 0.75 - 1.0m/s.

Isolating Before Integrating in Rehabilitation & Return-To-Play settings

In the context of rehabilitation, priority is given to exercises that are aimed towards rebuilding the capacity of the injured muscle, joint, tendons and/or ligaments. In my return-to-play protocols for my athletes, I will place single-joint, stability and balance-based exercises in the beginning of the training session before integrating them back into strength and plyometric exercise regressions.

Since our main goal is rebuilding the athletes’ capacities, velocities and force-outputs are not expected to be high, therefore there will be little detrimental effects to placing those exercises last.

Anecdotally, my athlete’s have reported feeling more confident in performing strength and plyometric exercises after an extended warm up and emphasis on their injured area.

Wrapping it up

Exercise sequencing should be individualized on an athlete-by-athlete basis using the principles of fatigability and priority, while taking into account special circumstances like performing advanced training protocols or managing injured athletes. While some can argue exercise selection has a larger impact influencing performance outcomes and that exercise order is of less importance, using principles for exercise sequencing bring a consistent and strategic approach to the design and implementation of a training session that cannot be overlooked by high performance athletes and coaches.