These questions were taken from my Instagram Story Q&A (@gcptraining). Alongside answering questions on Instagram, I will pick the best 3 questions related to combat sports S&C and discuss them in-depth. Some of these questions were asked by followers and readers of my newest ebook “The Strength & Conditioning Handbook for Combat Sports”.

Question #1 - What is the difference between squats and trapbar deadlifts? They both have similar joint angles.

To the naked eye, they have similar joint angles - especially if you’re using the high handles of a trap bar, meaning you’re “sitting” much deeper into the deadlift. Even if this is the case, squats should have a much larger degree of knee flexion, stimulating more of the distal quadriceps and lower leg muscles.

In terms of programming, there are distinct scenarios where I would use one over the other.

The trapbar deadlift is one of the exercises in the weight room that allows an athlete to lift the most weight. Because of this, I use this to build systemic, full-body strength through high-intensity loads. Although the degree of knee flexion is larger than other variations like the conventional or Romanian deadlift, an emphasis is still being put on the muscles of the mid- and lower-back. Trapbar deadlifts play a big role in improving “pulling-strength” in my combat sport athletes.

In contrast, when I want to build more robust knees and lower-body “pushing-strength”, I prescribe squats. Front squats, safety bar squats, back squats, heels-elevated cyclist squats; any variation that I can load safely and effectively with my athletes and achieve the deep knee flexion angles we want to see in order to develop quad strength.

QUESTION #2 - How would you structure hypertrophy phase while doing MMA?

I wouldn’t. Muscle hypertrophy is rarely a training goal for combat athletes, unless they’re trying to move up a weight class and even then, that is better performed over the span of several months or years, not through a 8 or 12 week phase.

If you find yourself in that position, the best options are to slowly increase the training volume of compound lifts and increase caloric intake over time. The key here is a gradual increase over the span of several training cycles. This way, the muscle soreness from sharp increases in resistance training volume will not disrupt skills training. As well, this gives time for the athlete to become acclimated to their increasing bodyweight.

There are more benefits to a high volume training phase than just hypertrophy.

Increased muscle coordination via repetition volume

Re-sensitization to high-intensity training

Muscular endurance and work capacity

Pair this with proper fueling and let hypertrophy be a by-product.

Question #3 - How would you start with plyometrics for a fighter that’s never done plyometric training before?

For lower body plyometrics like jumps and hops, start with “extensive” plyometrics. Also known as low level plyometrics. Simple exercises like plyometric pogo hops can be prescribed to help the fighter familiarize themselves with redirecting energy/force before moving onto more intensive plyometrics like depth jumps and lateral bounding.

Because extensive/low-level plyometrics are lower impact, they can be trained with relatively high volumes which in turn, will develop favourable tendon and muscle properties that will aid in getting the most out of intensive plyometrics.

For the upper body, exercises like assisted plyometric push ups as well as continuous medicine ball slams are a good choice.

FREE EBOOK CHAPTER DOWNLOAD!

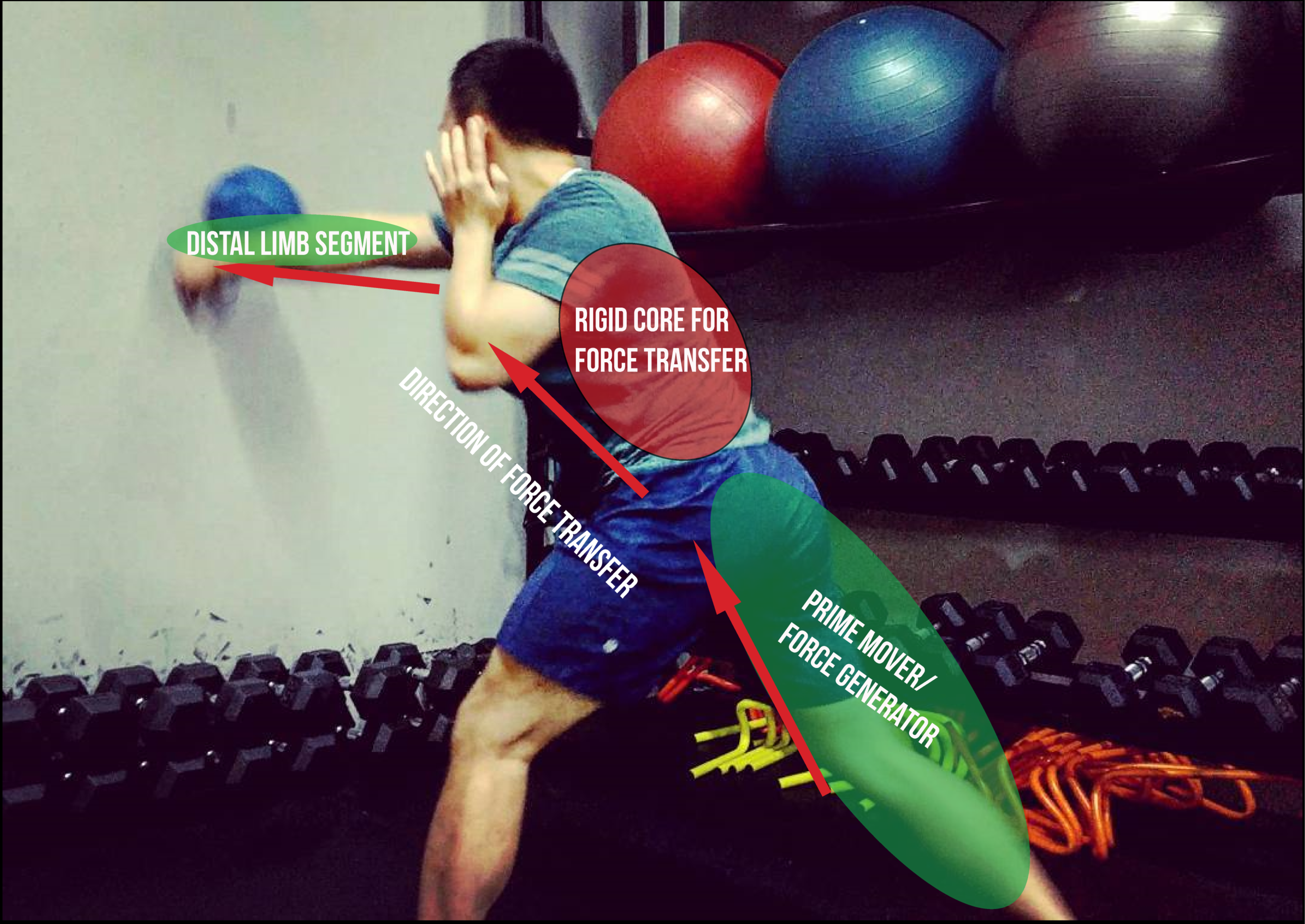

Chapter 7 of the eBook, “The Sport-Specific Trap - Revisiting Dynamic Correspondence for Combat Sports” talks about key concepts to consider when selecting exercises to enhance combat sports performance and some common mistakes coaches make.

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning - Microcycle & Within-Session Programming [Part 2 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605708338077-FWV40X4D3O675XD8QX5Q/Shared+from+Lightroom+mobile.jpg)

![Combat Sports Strength and Conditioning : Macrocycle & Mesocycle Planning [PART 1 of Programming Layers Series]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1605110722911-P7CE6O4VILYCVBEJ9R58/muay-thai-jump-rope.jpg)

![[Fight Camp Conditioning Guest Post] Bridging The Gap: Conditioning For Combat Sports](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55072bf0e4b055a8f66250e9/1585917228624-NZJGW93SQK2P6F890J2A/New+article+title+pic.jpg)